The Spanish researchers Daniel Oto-Peralías and Diego Romero-Ávila, from St. Andrews University and Universidad Pablo de Olavide, respectively, have recently published a study on the long-term effects that the Frontier of Granada had on historical inequality in Andalusia. The study has been published in the Journal of the European Economic Association and was presented at the 2015 Royal Economic Society Annual Conference held in Manchester.

The results of the research project show that the prevalence of large estates (latifundia) in modern and contemporaneous Andalusia was the consequence, in part, of the Frontier of Granada. The defense needs derived from the existence of the frontier with the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada gave rise to the concentration of land ownership and political power in the hands of the nobility. This fact constituted the starting point for the high economic and political inequality that has characterized a great bulk of the Andalusian territory since then.

To reach these conclusions, the authors compare municipalities that were conquered and resettled under the influence of an insecure frontier, on the Castilian side, with municipalities that were organized and repopulated after the dismantlement of the frontier, on the Granada side. On the one hand, the Castilian part was organized and resettled under the premises of being an insecure frontier region, which decisively affected the way the resettlement was done. This created a political equilibrium biased toward the privileged orders (particularly the nobility) which brought about a high concentration of de facto political power in the form of great land allocations and de jure political power through jurisdictional rights along the frontier. Other factors such as the insecurity of a frontier area constantly under threat promoted a type of extensive land exploitation based on pasture and livestock, and the low population density –a consequence of this insecurity– was also conducive to the accumulation of land in a few hands. In short, the frontier was able to fulfill the needs of both the Crown and the nobles. The former secured frontier positions that were difficult to defend and were at constant risk, while the latter found in the frontier a means of social, economic, and political empowerment.

On the other hand, the former Nasrid Kingdom of Granada evolved differently, largely because once it had been conquered by the Catholic Monarchs, the phenomenon of the frontier ceased to exist, and Andalusia was no longer a frontier region. The territory could be repopulated and organized according to different premises and objectives, which required a lower involvement of the nobility in this process. This rendered a relatively more egalitarian distribution of land and the creation of fewer lordships.

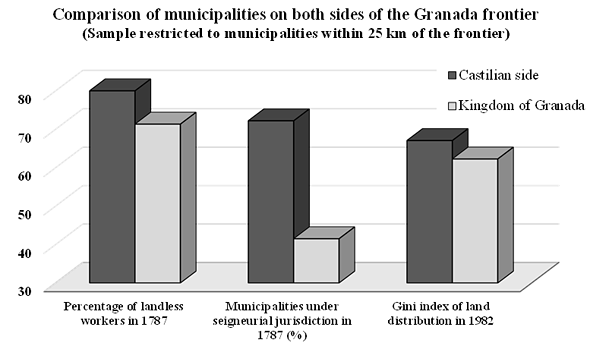

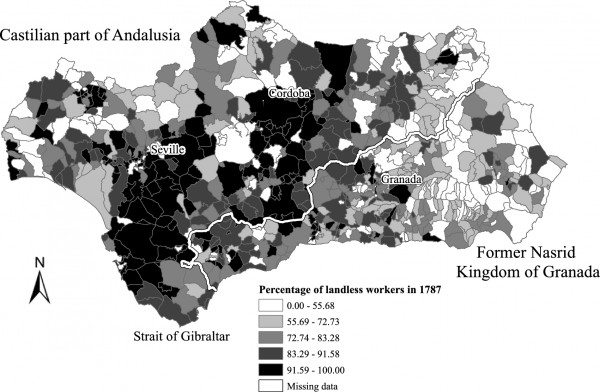

The empirical strategy implemented exploits municipality-level data to study the effect of the frontier of Granada on the concentration of economic and political power on the Castilian side. The authors compile historical data for the 771 municipalities making up modern-day Andalusia. The comparison of the municipalities on the Castilian side of the frontier (approximately the present provinces of Córdoba, Cádiz, Jaén and Sevilla) with those on the Granada side (approx. Almería, Granada and Málaga) renders a more unequal land distribution, a higher concentration of wealth and greater political power in the hands of the nobility in those municipalities on the Castilian side. Data from the 1787 Population Census of Floridablanca indicate that the percentage of landless workers over the total agricultural active population was 87.4% on the Castilian side (the highest in Spain), versus 72% on the Granada side. Concerning the presence of lordships, the proportion of municipalities under this regime was much higher on the Castilian side (65% vs. 42.5%). Along similar lines, data from the Catastro de Ensenada compiled between 1750 and 1753 also favor a higher concentration of wealth on the Castilian side.

The central part of the analysis restricts the sample to municipalities within 25 kilometers of the frontier. This allows for the comparison of municipalities that share similar geographic and climatic features. Indeed, the geographical analysis shows no significant differences in such geographical and climate characteristics as altitude, terrain ruggedness, rainfall, aridity, soil quality, etc. In contrast, statistically significant differences in political and economic inequality are found across the border, with higher inequality on the Castilian side. It is remarkable that indicators of land inequality measured in the 1980s show that the effect of the frontier of Granada persists today, five centuries after it disappeared, thus reflecting the high persistency of this phenomenon. The following figure summarizes the main results of the study:

Finally, one may wonder whether the Frontier of Granada has had consequences beyond generating political and economic inequality. The answer is that it probably has. The study shows that frontier-induced historical inequality has affected the welfare level of municipalities. As a matter of fact, people living in municipalities on the Castilian side has a lower socioeconomic condition, a lower number of cars per capita, and a lower education level (of those between 30 and 39 years).

One may conclude that it is history, instead of geography, that explains the patterns of land inequality in Andalusia. In addition, historical inequality resulting from the Frontier is a key factor in explaining the relative economic stagnation of this region. More generally, this study sheds light on how the dynamics of being a frontier region and the associated defense needs can create the appropriate conditions for the emergence of oligarchic societies, with negative consequences for long-term prosperity.

Reference:

Oto-Peralías, D. & Romero-Ávila D. (2017). “Historical Frontiers and the Rise of Inequality. The Case of the Frontier of Granada”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 15, num. 1, pp. 54-98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvw004