Competencia digital en los jóvenes de la generación alfa: retos y oportunidades en la sociedad tecnológica1

Digital competence in young people of the alpha generation: challenges and opportunities in the technological society

Salvador Gutiérrez Molero

Universidad de Cádiz

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2895-6154

salvador.gutierrezmolero@gm.uca.es

Hugo Heredia Ponce

Universidad de Cádiz

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3657-1369

Manuel Francisco Romero Oliva

Universidad de Cádiz

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6854-0682

RESUMEN

Las constantes transformaciones tecnológicas han dado lugar a la denominada Sociedad Digital, la cual se desarrolla cada vez más, en espacios virtuales. En este contexto, la generación Alfa se corresponde como la más expuesta y familiarizada con los dispositivos digitales desde una gran diversidad hacia su dominio y concepción. En este estudio se pretende analizar el nivel de conocimientos, habilidades, actitudes y emociones que tienen los estudiantes de 5.º y 6.º de Educación Primaria ante el uso de la tecnología. Para ello, se ha llevado a cabo un enfoque cuantitativo, con un diseño no experimental, transversal y exploratorio, con una muestra de 274 estudiantes de cinco centros educativos de la provincia de Cádiz. Para recoger los datos se utilizó el cuestionario Bastarrachea et al. (2023). Los resultados evidencian que la madre actúa como consejera sobre cómo deben utilizar las tecnologías sus hijos. Y, además, aunque los jóvenes tienen unas habilidades aceptables, no cuentan con buenos conocimientos tecnológicos.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Sociedad Digital; Generación Alfa; Competencia digital; TIC; Cuestionario.

ABSTRACT

The constant technological transformations have given rise to the so-called Digital Society, which is increasingly developing in virtual spaces. In this context, the Alpha generation corresponds as the most exposed and familiarised with digital devices from a great diversity towards their mastery and conception. The aim of this study is to analyse the level of knowledge, skills, attitudes and emotions that 5th and 6th grade primary school students have towards the use of technology. For this purpose, a quantitative approach has been carried out, with a non-experimental, cross-sectional and exploratory design, with a sample of 274 students from five schools in the province of Cadiz. The Bastarrachea et al. (2023) questionnaire was used to collect the data. The results show that mothers act as advisors on how their children should use technology. Furthermore, although the young people have acceptable skills, they do not have good technological knowledge.

KEYWORDS

Digital Society; Alpha Generation; Digital Competence; ICT; Questionnaire.

1. INTRODUCTION

Today’s society is immersed in a constant increase in the amount and speed of data, which has led to a digital revolution. According to Polo-Roca (2020), the link between technology and digitalisation has given rise to a model of society characterised by developing mainly in virtual or digital spaces, thus promoting the so-called Digital Society. In this sense, digital society is supported by smart devices and other instruments, whose productive and communicative practices are conducted mainly through digital media, thus changing the different structures and forms of communication and interaction (Reyero-Sáez, 2019; Sunker & Ullmann, 2019; Rivera-Vargas, 2018).

In the same vein, Area-Moreira et al. (2022), argue that digital society, also known as Society 4.0, is characterised by automation and increased speed of computational processes, the development of artificial intelligence and the digitisation of services and products. Similarly, Chinchilla et al. (2021) and Colina-Vargas (2024) highlight that digital technologies have brought about changes in various social, professional, administrative and academic spheres.

In line with the above, this digital society means that socialisation and relationships take place in virtual environments such as social media, entertainment is obtained through streaming platforms, and education can be distance learning (Kalsoom et al. 2022) or that crimes are committed via the internet. This is the context for new reading practices through new digital media and formats that are becoming widespread in society in general and have an impact on educational contexts in particular, both in the transmission and reception of content (Tabernero-Sala et al., 2020), considering that a biliterate reading brain is developing (Wolf, 2020), originating from the onset of literacy in print format and its subsequent inclusion in digital media through multimedia epitexts characteristic of the digital age (Álvarez-Ramos & Romero-Oliva, 2018).

Therefore, digital citizens must command the necessary skills to use technology in a way that allows them to face the problems inherent in modernity and digital society (Maldonado-Pérez, 2024; Alastor et al. 2024; Chinkes & Julien, 2019; Polo-Roca, 2020; Rivera-Vargas, 2018).

With regard to the need to master technology from an aptitude perspective, García-Contador and Gutiérrez-Esteban (2020) and Olvera (2022) point out that the technological transformation that has influenced the economy, culture, health, trade, among others, has also had an impact on education, which cannot remain isolated from the digital revolution. Education administrations are implementing programmes to promote the use of Information and Communication Technologies (hereinafter ICT), which means that schools need to provide skills training to both their professionals and their students. This is the case of the Spanish Government, which has a Plan for Digitalisation and Digital Skills in the Education System for 2026, with an investment of over EUR 1.4 billion, aimed at advancing and improving the digitalisation of education. Organic Act 3/2020, of 29th December, amending Organic Act 2/2006, of 3rd May, on Education (LOMLOE, 2020), establishes in the Primary Education curriculum that digital competence ‘involves the safe, healthy, sustainable, critical and responsible use of digital technologies for learning, work and participation in society, as well as interaction with them’. Furthermore, it sets forth that literacy in information, communication, media education, digital content creation, security, issues related to digital citizenship, privacy, intellectual property, among others, must be developed. It is therefore essential that primary school students develop ICT knowledge and skills.

In this context, it is essential to modify teaching methods, integrating new technological tools into the classroom with the aim of developing digital competence so that students can function fully in 21st-century society and improving teaching and learning processes (Alonso-Ferreiro and Zabala-Cerderiña, 2021; Colomo-Magaña & Cívico-Ariza; Lena-Acebo et al., 2023). Furthermore, it is believed that integrating technology into the classroom can motivate students and encourage knowledge acquisition by associating it with positive emotions such as enjoyment and eliminating emotions that can lead to frustration (Córcoles-Charcos et al., 2023; Brown et al., 2020). For all these reasons, it is necessary to understand a generation that was born and is growing up immersed in the digital world, and which is currently the target audience for education. We are talking about the Alpha generation (García-Aretio, 2019).

This Alpha generation, a term coined by McCrindele (2023) to refer to individuals born between 2010 and 2025, is characterised by its inherent ability to adapt to digital technology, as they are exposed to digital devices from an early age (Rose & Rani-Thomas, 2024; Talan et al., 2024). Along the same lines, Cortés-Quesada and Vizcaíno-Verdú (2025) and Gil-Fernández and Calderón-Garrido (2023) state that members of the Alpha generation are adapted to technology from an early age and across the board, with social media being their main means of communication. This is causing them to be less critical, avoid socialising and not develop their own identity, which leads to mental health challenges such as Hikikomori syndrome, a social phenomenon characterised by isolation and limited interaction (Serrano-Yánez, 2021; Sanromán-Aranda, 2022).

In this regard, research such as that carried out by Alarcón-Mendoza (2024) and Casado and Sánchez (2022) shows that there is a strong positive correlation between the effect of social media on behaviour and an increase in emotional disorders such as insecurity and anxiety. According to Deci and Ryan (2000), this is related to Self-Determination Theory, which argues that human motivation is influenced by the pursuit of three needs: autonomy (control over one’s own decisions), competence (being able to interact with others) and relatedness (feeling connected and belonging to a group). Likewise, according to Lucciarini et al. (2021), the Alpha generation, constantly exposed to social media and seeking external validation, can fall into eating disorders such as anorexia in pursuit of the ‘perfect’ body. These data demonstrate the importance of educating the Alpha generation in the use of ICT and the amount of time they spend exposed to screens (Ortiz de Villate et al. 2023).

In relation to the above, Palacios-Núñez and Deroncele-Acosta (2020) highlight the importance of including the socio-emotional dimension in existing digital literacy models. Similarly, Mayisela (2018) and Area-Pessoa (2012) emphasise that in order to achieve digital literacy among citizens, it is essential to take into account socio-emotional aspects beyond instrumental, cognitive-intellectual, communicational and axiological skills.

Similarly, Sramova and Pavelka (2023) and Cirilli et al. (2019) point out that this generation differs from others in its commitment to technology and visual media from the earliest stages of development, thus having daily interaction with digital devices and, in general, high digital competence.

Although the Alpha generation may possess high digital skills, having been the first to grow up in a completely digital environment, the labour market is undergoing transformations generated by technological development, and this generation is not prepared for the new job landscape. According to numerous studies, so many new fields of work are emerging that it is estimated that 68 % of the jobs that this generation will occupy do not yet exist (Soto-Galarza et al., 2025; Coello, 2023). For this reason, Capelo et al. (2024) and Vázquez-Cano et al. (2017) argue that educational approaches must be modified in order to promote digital competence from an early age.

It is also important to note that familiarity with technology leads children of this generation to be less cautious about their actions in digital environments, which is why it is important for the education sector to work on the different aspects of technology with members of this generation (Lanulli, 2020). For example, primary school students should have the knowledge that allows them to understand what a digital footprint is and how personal information is shared on different digital platforms, as these students are a particularly vulnerable group due to their lack of understanding of the consequences and scope of internet misuse (Sánchez-Díaz, 2024; Pedrouzo & Krynski, 2023).

In conclusion, the digital society has transformed the way we interact and participate in society, which increasingly demands greater technological competence from its citizens. That is why the educational environment must adapt to the Alpha generation, who are born and raised in completely digital environments. However, this does not mean that they are critical of the risks of the internet. It is thus essential to rethink teaching approaches in order to integrate ICT into the classroom and develop digital competence in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes, the latter being the subject of research which shows that there is a positive attitude towards the use of ICT (Regueira & Alonso, 2022).

Therefore, the objective of this research is to determine what knowledge, skills, attitudes, and emotions 5th and 6th grade primary school students have regarding the use of technology. Therefore, several research questions are established:

•What is the profile of 21st-century students of the so-called Alpha Generation?

•Are there differences in the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and emotions of students based on the establishment they attend, their gender, and their year?

•Is there a relationship between your knowledge and their skills in relation to technologies?

•Is there a link between the person who informs me most about how to use electronic devices and the skills possessed by the student?

2. METHODOLOGY

This study falls within the quantitative paradigm in order to fulfil the objective and attempt to answer the questions posed. Therefore, a non-experimental, cross-sectional, exploratory method was used (Hernández-Sampieri & Mendoza-Torres, 2018).

2.1. Sample2

This research, which was conducted between March and April 2025, was based on a non-probability convenience sample involving 5th and 6th grade primary school students from five schools in the Bay of Cádiz. In accordance with ethical considerations, the anonymity of both the students and the establishment was guaranteed, as agreed by the management team. The sample consists of a total of 274 students distributed as follows (Table 1):

Table 1. Distribution of the sample by educational establishment, gender and year.

|

Centro |

Gender Year |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Establishment 1 |

Girl |

5th year |

2 |

22.2 |

|

6th year |

7 |

77.8 |

||

|

Total |

9 |

100.0 |

||

|

Boy |

5th year |

3 |

50.0 |

|

|

6th year |

3 |

50.0 |

||

|

Total |

6 |

100.0 |

||

|

Establishment 2 |

Girl |

5th year |

13 |

72.2 |

|

6th year |

5 |

27.8 |

||

|

Total |

18 |

100.0 |

||

|

Boy |

5th year |

11 |

73.3 |

|

|

6th year |

4 |

26.7 |

||

|

Total |

15 |

100.0 |

||

|

Other |

5th year |

1 |

100.0 |

|

|

Establishment 3 |

Girl |

5.º |

9 |

39.1 |

|

6.º |

14 |

60.9 |

||

|

Total |

23 |

100.0 |

||

|

Boy |

5.º |

9 |

50.0 |

|

|

6.º |

9 |

50.0 |

||

|

Total |

18 |

100.0 |

||

|

Other |

5.º |

2 |

100.0 |

|

|

Establishment 4 |

Girl |

5.º |

25 |

47.2 |

|

6.º |

28 |

52.8 |

||

|

Total |

53 |

100.0 |

||

|

Boy |

5.º |

42 |

50.6 |

|

|

6.º |

41 |

49.4 |

||

|

Total |

83 |

100.0 |

||

|

Other |

5.º |

1 |

100.0 |

|

|

Establishment 5 |

Girl |

5.º |

10 |

35.7 |

|

6.º |

18 |

64.3 |

||

|

Total |

28 |

100.0 |

||

|

Boy |

5.º |

11 |

68.8 |

|

|

6.º |

5 |

31.3 |

||

|

Total |

16 |

100.0 |

||

|

Other |

6.º |

1 |

100.0 |

|

Source: SPSS

2.2. Assumption

In this research, based on the questions, the following assumptions were established:

1.There are significant differences between the dimensions (1, 2, 3 and 4) and the year.

2.There are significant differences between the dimensions (1, 2, 3 and 4) and the gender.

3.There are significant differences between the dimensions (1, 2, 3 and 4) and the establishment.

4.There are significant differences between the dimensions 1 and 2.

5.There are significant differences between the person who informs me most about how to use electronic devices and the skills possessed by the student.

2.3. Instrument

In relation to the instrument, the questionnaire designed and validated by Bastarrachea et al (2023) with a Cronbach’s alpha of.936 was used. It is divided into four well-defined dimensions: knowledge (d1), skills (d2), attitudes (d3) and emotions (d4). Each of them has a Cronbach’s alpha greater than.80. In addition, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis was performed to validate this questionnaire. For the first variable, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was performed, with a result of.803, and Bartlett’s sphericity test (x2 = 6479; gl= 2485; p = <.001). These data is correct. As for the AFC data, the data was suitable: (χ2 = 5834.402; gl = 2408; p = <.001; CFI =.920; TLI =.918; RMSEA =.100 [IC 90 %:.097-.103]; SRMR =.133). For the sociodemographic section, the questionnaire designed by Sáinz-Ibáñez (2007) was used.

2.4. Procedure

To develop the results, the following statistical tests were performed using SPSS v.29.0.2.0:

1.Descriptive analysis

2.Significance tests (Wilcoxon W and Kruskal-Wallis H). To establish levels, ranges were established shed for each level, as shown below (Table 2):

Table 2. Mean ranges according to levels.

|

Dimensions |

None |

Little |

Fair |

Very much |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Knowledge |

2.00-2.50 |

2.51-3.00 |

3.01-3.50 |

3.51-4.00 |

|

2. Skills |

1.00-1.75 |

1.76-2.50 |

2.51-3.25 |

3.26-4.00 |

|

3. Attitudes |

2.00-2.50 |

2.51-3.00 |

3.01-3.50 |

3.51-4.00 |

|

4. Emotions |

1.00-1.75 |

1.76-2.50 |

2.51-3.25 |

3.26-4.00 |

Source: Prepared by the authors

2.5. Analysis of correlations according to Spearman

In accordance with legal and ethical considerations, this research followed the protocol of the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, in keeping with open science, the research data is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15359020

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive analysis

In the analysis of the students’ profiles, it can be said that 98.9 % have electronic devices such as mobile phones, computers, tablets, etc. In addition, 98.5 % have an internet connection and 32.5 % use it for more than 10 hours a week to play games (50.7 %).

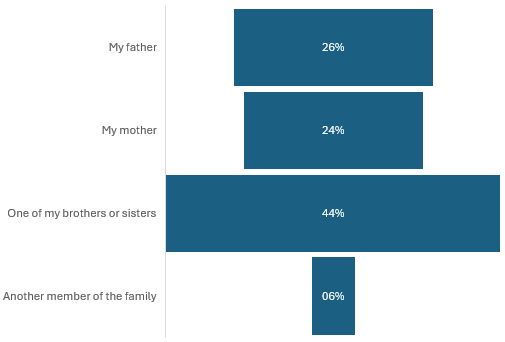

When analysing the family environment, siblings are the most frequent users of electronic devices (44.2 %), followed by fathers with 26.3 % (Figure 1). This may be due to their similar ages or when they started using technology.

Figure 1. Person who uses electronic devices most frequently.

Source: SPSS

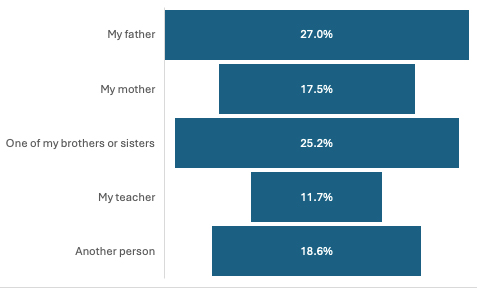

Peers within the family, i.e. siblings, are the ones who have encouraged them most to use technology (Figure 2), followed by their father with 27 %. It is noteworthy that only 11.7 % of teachers encourage their use.

Figure 2. Person who most encourages the use of electronic devices.

Source: SPSS

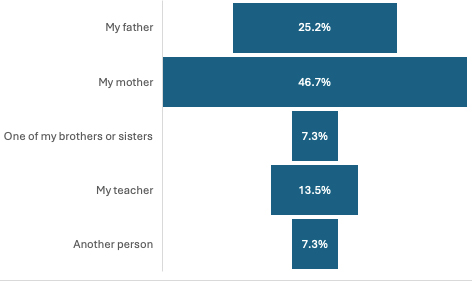

On the other hand, mothers (Figure 3) discourage their use the most and exercise greater control over students’ use (46.7 %), while siblings and other people do so the least (7.3 %).

Figure 3. Person who most discourages the use of electronic devices.

Source: SPSS

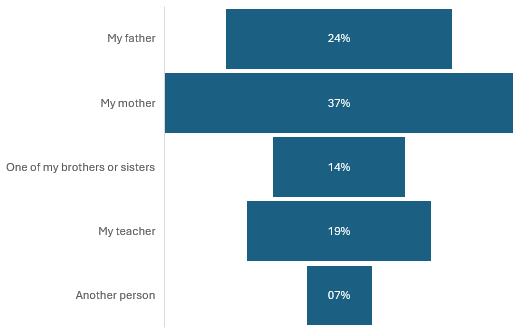

Along the same lines, highlighting the foregoing, mothers are also the ones who provide the most information to students about how to use them (36.5 %), while only 19.3 % of teachers inform students about their correct use.

Figure 4. Person who provides the most information on how to use electronic devices.

Source: SPSS

3.2. Significance tests

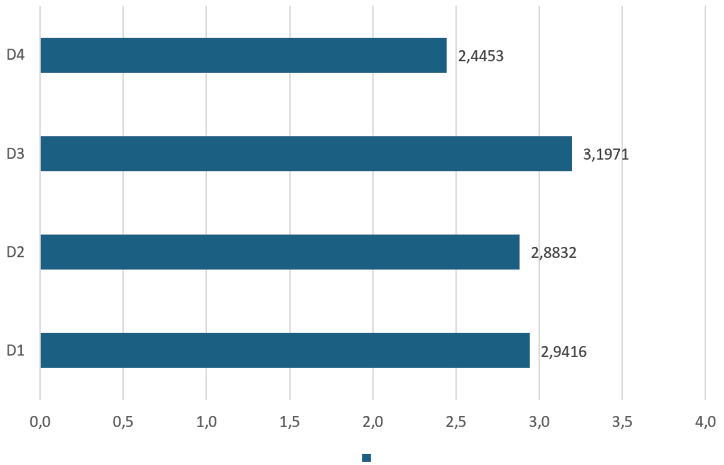

A general study of the sample (Figure 5) shows that students have poor knowledge of technologies, although their skills are moderate. In addition, students have a moderate attitude (dimension 3) towards technologies and do not experience any emotional reactions.

Source: SPSS

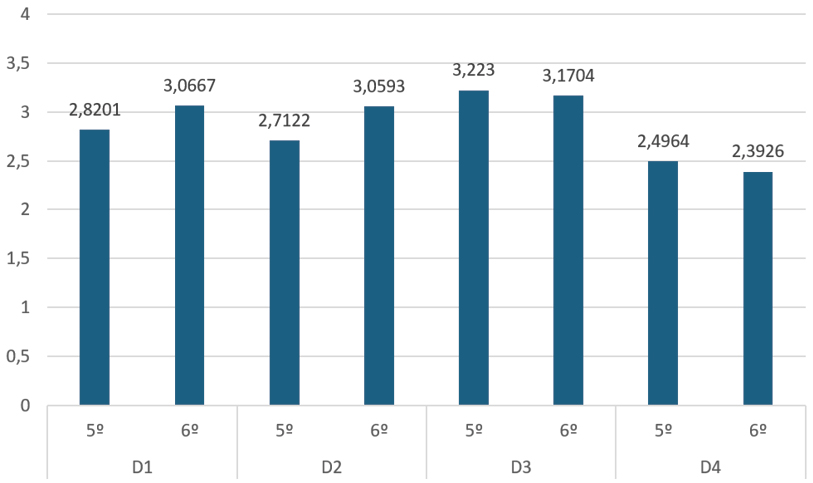

In the comparison between the different courses (Figure 6), there is significance (.001<.05; Wilcoxon W 17246.5 and 16447 respectively) only in dimensions 1 and 2 in favour of the 6th-year students. Therefore, we reject the null assumption and accept the alternative assumption. The latter course has an acceptable level of knowledge, compared to the 5th-year students, who have little knowledge. As for skills, both can be improved, as they are limited, although the level is better in 6th year. There are no significant differences in the other two dimensions. In relation to dimension 3 (.331>.05; Wilcoxon W 18005), both courses have a moderate attitude towards technologies, but with a higher average in Year 5. In contrast, they display few emotions (.130>.05; Wilcoxon W 17700.5) at both educational levels. In these cases, we assume the null assumption.

Figure 6. The average dimensions in relation to educational levels.

Source: SPSS

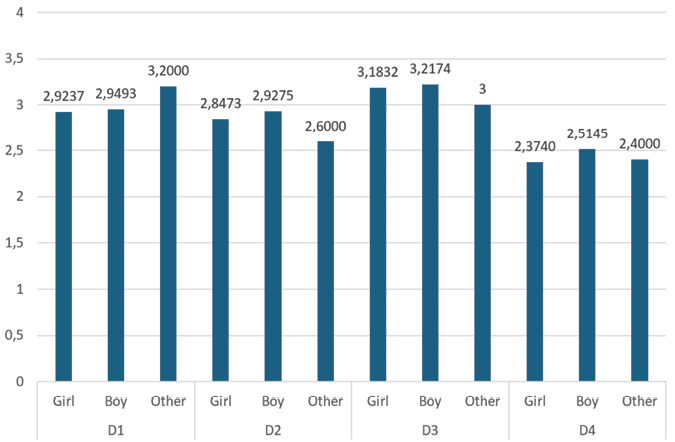

As for the comparison between genders (Figure 7), there are no significant differences in any of the dimensions (p>.05). Therefore, we assume the null assumption. In dimension 1 (.635>.05, Kruskal-Wallis H.909), girls and boys have little knowledge of technology compared to those in the ‘other genders’ category, whose knowledge is acceptable. In terms of skills (.374>.05, Kruskal-Wallis H 1.968), all genders show limited skills, with a lower average in ‘other’ than boys and girls. In dimension 3 (.767>.05, Kruskal-Wallis H.531), the opposite situation occurs to that in dimension 1, as the ‘others’ show few attitudes towards others (girls and boys) and a moderate attitude towards technology. And finally, girls and ‘others’ experience few emotions (.052>. 05, Kruskal-Wallis H5.908) compared to boys who, even if only minimally, show greater restraint.

Figure 7. Average dimensions in relation to gender.

Source: SPSS

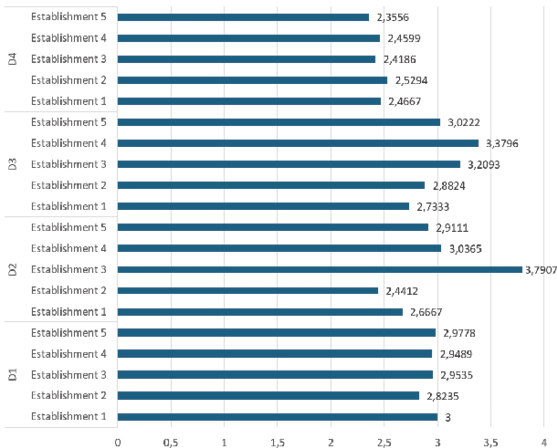

In the analysis of educational establishments (Figure 8), there are significant differences in dimensions 2 and 3, with the average being higher in establishments 3 and 4, respectively. With regard to dimension 1 (.847>.05, Kruskal-Wallis H 1.385), in all establishments, there is little knowledge. In contrast, in dimension 2 (.001<.05, Kruskal-Wallis H 26.122) establishments1 and 3 have acceptable skills, but establishment 2 has few. As we have seen, establishment 3 has many skills with regard to the use of technology. As for attitudes (.001<.05, Kruskal-Wallis H 33.308), establishments 1 and 2 show few, compared to the others, which are moderate, with establishment 4 standing out with the highest average. In relation to dimension 4 (.676>.05, Kruskal-Wallis H 2.324), it is found that all establishments show few emotions, compared to establishment 2, where their presence is moderate.

Figure 8. Average dimensions in relation to educational establishments.

Source: SPSS

3.3. Correlation analysis

In this analysis, one of the first considerations will be to look at the correlation between knowledge and skills. Table 7 shows how students who have greater knowledge of technologies also have better skills to develop in them. Although this correlation is significant, the p-value is.0664, which does not indicate a strong link, so the alternative hypothesis can be accepted.

Table 7. Correlation between knowledge and skills dimensions.

|

D1 |

D2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Spearman’s Rho |

D1 |

Correlation coefficient |

1.000 |

.664** |

|

Next (bilateral) |

. |

<.001 |

||

|

N |

274 |

274 |

||

|

D2 |

Correlation coefficient |

.664** |

1.000 |

|

|

Next (bilateral) |

<.001 |

. |

||

|

N |

274 |

274 |

||

Source: SPSS

The second correlation to be analysed shows that there is no significant relationship between the skills that students possess and the person who provides them with the most information on how to use electronic devices (,632>,05) (Table 8). Therefore, the null assumption is accepted.

Table 8. Correlation between skills and the person who reports the most use of electronic devices.

|

D2 |

The person who informs me most about how to use electronic devices is |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Spearman’s Rho |

D2 |

Correlation coefficient |

1.000 |

.029 |

|

Next (bilateral) |

. |

.632 |

||

|

N |

274 |

274 |

||

|

The person who informs me most about how to use electronic devices is |

Correlation coefficient |

.029 |

1.000 |

|

|

Next (bilateral) |

.632 |

. |

||

|

N |

274 |

274 |

||

Source: SPSS

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study has determined the profile of these students and their characteristics. Based on their date of birth, they could be classified as Generation Alpha (McCrindle, 2014), as most of them have electronic devices, are connected to the internet and spend more than 10 hours a week playing games, or, in the words of Rangel et al. (2021, p.140), ‘Mobile devices and apps are part of children’s everyday lives and are integrated into social spaces.’

The family environment is very important, as it must adapt to the digital world of their children so that they can guide them, advise them and resolve conflicts on social media (Martín-Vivar, 2021). In line with this, our study showed that mothers become advisors (Palacio, 2003). And according to our study, they are also the ones who most discourage their children from using them (46.7 %). Furthermore, teachers are important in this technological training, although in our study only 19.3 % have been informed about how to use them. This may be because current teachers may have little training and are afraid to explain how to use them properly (Flores-Tena et al., 2021). It should be noted that this lack of knowledge or training is not only found among teachers, but also among families, as there is a generation gap between them and their children (López-Sánchez & García del Castillo Rodríguez, 2017).

In this regard, the results reflect the need to establish teacher training programmes aimed at improving digital competence, since, as mentioned above, teachers play a less influential role in digital matters than other family members such as siblings and parents. These findings highlight the opportunity for improvement with regard to the role of teachers as critical mediators in the use of technology. Therefore, the main training action established is to reinforce teaching programmes that develop technical skills, but also pedagogical and ethical aspects regarding the use of digital elements (Martins & Carvalho, 2024). Likewise, these teacher training programmes should be approached from a skills-based perspective, incorporating practical workshops that address aspects such as digital content development, virtual classroom management, cyber coexistence, and the use of digital educational platforms, among other topics. Strategies should also be implemented to ensure that teachers are role models in the responsible use of technology by promoting good practices on the internet (Sánchez-Antolín et al., 2014).

In the concept of the generation gap, knowledge and skills are two elements that can be used—it would be impossible to distinguish between good and bad use. This research has generally shown that they have little knowledge of, for example, copyright, licences and restricted materials, how cloud storage works, video conferencing platforms, etc. This is because they focus more on the knowledge, they need to play games and are unaware of the full potential and dangers that this lack of knowledge can entail. This was further exacerbated by the pandemic (Munar et al., 2025). This results in poor skills in this case (Núñez-Naranjo, et al., 2025). In fact, our study has demonstrated this correlation (.001<.05;.664), although it is not strong, as it has been verified that students have poor knowledge and moderate, acceptable skills.

When comparing 5th and 6th-year students, there are significant differences in knowledge and skills, although the averages are similar. It can be concluded that in the third cycle there are no major differences between them (Villegas et al., 2017; Antonio et al., 2006). In terms of gender, there are no significant differences either, as in general they have little knowledge and their skills are limited, with a slightly higher average among boys and those who identify with other genders. However, studies such as those by Aesaert and Van Braak (2015) show that girls have greater control than boys. They have little knowledge about the differences between the educational establishments, but there are significant differences in terms of size, as establishment 4 has many skills compared to the others, which are not as good. This is consistent with the limited technological education provided in schools to enable students to ultimately acquire good digital skills, as required by the act on education.

Digital management, as shown by studies by Carcelén-García et al. (2024), Merejildo y Silva (2024), It evokes emotions and attitudes in young people, considering them ‘affective technologies’ (Serrano-Puche, 2015). This research has demonstrated that students experience a moderate attitude and few emotions when using technology. As for the courses, there are no significant differences, as both show a moderate attitude, although with a greater presence among 5th-year students. Instead, they show few emotions. All of this may be because they have been immersed in the technological world since the beginning (Romero et al., 2021; Alonso-Ferreiro et al., 2019). In relation to gender, there are no significant differences, but it should be noted that boys convey more emotions than girls. We could look for a link with the use of games, as the study carried out by Tejada-Garitano (2024) indicates that boys use them more than girls and that games produce emotions (González & Blanco, 2008). With regard to educational establishments, there are no significant differences, but establishments 1 and 2 show few attitudes, unlike establishment 4, which has a greater presence of attitudes. Therefore, in terms of emotions, all subjects display few emotions, but the establishment has a moderate presence. Therefore, from these last few lines, it can be seen that schools must also work on this socio-emotional competence that is present in our daily lives and has a direct impact on the use of technology.

These results reveal the need to incorporate emotional aspects into digital literacy programmes, since the absence of emotions when using technology could indicate an instrumental and decontextualised relationship focused solely on consumption. This contrasts with the importance of emotions from a pedagogical perspective, since they are fundamental to commitment, motivation and autonomous learning, as developed in Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Therefore, it is advisable to include training activities that integrate the emotional component.

As a pedagogical interpretation of the differences between educational establishments, it is found that the analysis between establishments revealed significant differences in skills and attitudes towards technology, with establishments 3 and 4 obtaining the best results. This could be interpreted based on the policies of each establishment, since educational establishments with greater digital competence could make greater investments in technological resources and promote educational plans aimed at developing digital competence (Sánchez-Antolín et al., 2014). These differences may also be due to the training of teachers in these establishments (González-Rodríguez et al., 2022).

One of the limitations of our study is the accessibility to more educational centres and also being able to conduct a questionnaire with families to analyse each family environment and identify digital profiles. Furthermore, as part of this study, a triangulation of school, students and family could be carried out, and the use of artificial intelligence could also be analysed.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

HHP, MFRO: Methodology, Validation. SGM, HHP, MFRO: Formal analysis, research, data curation, revisions and corrections, supervision. HHP: Draft of original text.

NOTES

1.This article is linked to the project PID2021-126392OB-I00 ‘Lecturas no ficcionales para la integración de ciudadanas y ciudadanos críticos en el nuevo ecosistema cultural (LENFICEC)’ and the doctoral thesis Contribución de los libros ilustrados de no ficción en el aprendizaje de materias no lingüísticas. Un estudio de diseño centrado en la competencia mediática e informacional by Salvador Gutiérrez Molero.

2.The names of the educational establishments are not specified in order to preserve anonymity.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

(2024). Las redes sociales y su impacto en la generación alfa: un análisis de comportamiento. Universidad Laica “Eloy Alfaro” de Manabí. https://repositorio.uleam.edu.ec/handle/123456789/6876

, & (2024). Competencia digital y diseño universal para el aprendizaje en la formación de maestros: un análisis multifactorial. Hachetetepé. Revista científica De Educación Y Comunicación, (29), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.25267/Hachetetepe.2024.i29.2206

, , & Actitudes de alumnado preadolescente ante la seguridad digital: un análisis desde la perspectiva de género. Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED), 19(61), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.6018/red/61/02

, & (2021). Competencia digital del alumnado de educación primaria de Galicia. Investigación: cultura, ciencia y tecnología, (25), 18-26. https://portal.reunid.eu/documentos/61933e496a8ab2204173bc46?lang=de

& (2018). Epitextos milénicos en la promoción lectora: morfologías multimedia de la era digital. Revista Letral, 20, 71-85. https://doi.org/10.30827/RL

, , & (2016). El desarrollo de las competencias digitales de niños de quinto y sexto año en el marco del programa de MiCompu.Mx en Tabasco. Perspectivas docentes, (61), 37-46. https://doi.org/10.19136/pd.a0n61.1858

, , & (2022). La transformación digital de la docencia universitaria. Profesorado, Revista De Currículum Y Formación Del Profesorado, 26(2), 1–5. https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/profesorado/article/view/25560

& (2012). De lo sólido a lo líquido: las nuevas alfabetizaciones ante los cambios culturales de la Web 2.0. Comunicar, 19(38), 13-20. http://doi.org/10.3916/C38-2012-02-01

, , & (2023). Diseño y validación de un instrumento para medir la competencia digital en estudiantes de educación primaria. PUBLICACIONES, 53(1), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.30827/publicaciones.v53i1.28059

Boletín Oficial del Estado. Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación (LOMLOE).

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , & (2020). EDUCAUSE Horizon Report Teaching and Learning Edition. EDUCAUSE.

, , & (2024). El ABP para el desarrollo de competencias técnicas en la UEF Isabel de Godín. Riobamba - Ecuador 2024. Dominio de las Ciencias, 10(3), 1983–2007 https://doi.org/10.23857/dc.v10i3.4020

, , & (2024). Territorios de la vulnerabilidad digital: situaciones, emociones y actitudes de los jóvenes en el entorno online. Revista Española de Sociología, 33(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.22325/fes/res.2024.208

& (2022). Revisión sobre la salud mental y nuevas tecnologías: análisis de las redes sociales y los videojuegos en las primeras etapas de desarrollo como factores modulares de una salud mental positiva. Revista INFAD de PsicologÌa. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 2(1), 79-88. https://revista.infad.eu/index.php/IJODAEP/article/view/79-88/2003

, & (2021). El rol docente y estudiante en la era digital. Revista Boletín Redipe, 10(2), 287-294. https://doi.org/10.36260/rbr.v10i2.1213

& (2019). Las instituciones de educación superior y su rol en la era digital. La transformación digital de la universidad: ¿transformadas o transformadoras? Ciencia y Educación, 3(1), 21-33. https://doi.org/10.22206/cyed.2019.v3i1.pp21-33

, & (2019). Digital skills from silent to Alpha generation: An overview. In Luis Gómez-Chova, Alicia López-Martínez & Ignacio Candel-Torres (Eds.), Edulearn. 11th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies (pp. 5134-5143). Actas de EDULEARN19.

(2023). La empleabilidad sostenible en personas mayores de 50 años en el sector financiero cooperativo. [Proyecto de Investigación fin de Licenciatura, Universidad Técnica de Cotopaxi]. https://repositorio.utc.edu.ec/items/72d0df37-82ff-4617-8772-a0540396dbc9

, , & (2024). Computational intelligence, educational robotics, and artificial intelligence in the educational field. A bibliometric study and thematic modelling. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 22, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.10369

& (2023). E-instantáneas culturales como recurso digital: análisis de su influencia en la competencia digital. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 19, 94-108. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.7569

, , & (2023). Uso de entornos de realidad virtual para la enseñanza de la Historia en educación primaria. Education in the Knowledge Society (EKS), 24, e28382-e28382. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.28382

& (2025). Deslizar, interactuar y conectar: Un análisis del comportamiento de consumo de la generación Alfa en TikTok. Icono14, 23(1), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v23i1.2183

, & (2000). El “qué” y el “por qué” de la búsqueda de objetivos: Necesidades humanas y la autodeterminación del comportamiento. Psychological Inquiry, 11 (4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

España digital 2026. El Plan de Digitalización y Competencias Digitales del Sistema Educativo. Plan #DigEdu. https://espanadigital.gob.es/lineas-de-actuacion/plan-digedu

, , & (2021). El uso de las TIC digitales por parte del personal docente y su adecuación a los modelos vigentes. Revista Electrónica Educare, 25(1), 1-21. http://doi.org/10.15359/ree.25-1.16

(2019). Necesidad de una educación digital en un mundo digital. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 22(2), 9-22. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.22.2.23911

& (2020). El rol docente en la sociedad digital. Digital Education Review, (38), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1344/der.2020.38.1-22

, & (2023). Challenges of social media in education. Review and bibliometric analysis of scientific production to map trends and perspectives. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 9(2), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2023.v9i2.16340

& (2008). Emociones con videojuegos: incrementando la motivación para el aprendizaje. Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información, 9(3) 69-92. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2010/201017343005.pdf

, , & (2022). Diferencias en la formación del profesorado en competencia digital y su aplicación en el aula. Estudio comparado por niveles educativos entre España y Francia. Revista española de pedagogía, 80(282), 371-390. 371-389. https://doi.org/10.22550/REP80-2-2022-06

, & (2018). Metodología de la investigación: las rutas cuantitativas, cualitativas y mixta. McGraw-Hil.

, , , , & (2022). Online Education amid COVID-19 Crisis: Issues and Challenges at Higher Education Level in Pakistan. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 18, 240–259. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.6429

(2020). El mercado de los niños del siglo XXI: la generación alpha y el desafío para las empresas. [Tesis de grado, Universidad de San Andrés. Escuela de Negocios]. Repositorio Digital San Andrés. http://hdl.handle.net/10908/18396

, , , & (2023). Social media and smartphones as teaching resources: Spanish teacher’s perceptions. Pixel-Bit. Revista De Medios Y Educación, 66, 239–270. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.96788

, & (2017). La familia como mediadora ante la brecha digital: repercusión en la autoridad. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Sociales, 8(1), 108-124. https://doi.org/10.21501/22161201.1928

, & (2021). Anorexia y uso de redes sociales en adolescentes. Avances en Psicología, 29(1), 33-45. https://doi.org/10.33539/avpsicol.2021.v29n1.2348

(2024). Jóvenes y consumo de información en redes sociales influencers y cambios en la percepción sobre el periodismo. Revista Argentina de Estudios de Juventud, 18, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.24215/18524907e081

& (2024). Formación de la competencia digital docente en la era de la inteligencia artificial. COMeIN: Revista de los Estudios de Ciencias de la Información y de la Comunicación, 8(144), https://doi.org/10.7238/c.n144.2446

(2018). Enhancing first-year students’ digital content creation at a South African university. Proceedings of theInternational Conference on e-Learning, ICEL, 243-248.

(2014). The ABC of XYZ: understanding the global generations. UNSW Press.

(2023). Generation Alpha. Hachette Australia.

, & (2024). La influencia de las tecnologías de la información y comunicación en el ámbito socioemocional. Revista Latinoamaericana de ciencias sociales y humanidades, 5(4), 2654. https://doi.org/10.56712/latam.v5i4.2445

, , , & (2025). Planes digitales de contingencia en los centros educativos de las Islas Baleares en pandemia. Aula Abierta, 54(1), 65-73. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.20832

, , , , & (2025). Desarrollo de Competencias Digitales en Estudiantes de Primaria. Digital Publisher, 10(1-2), 128-154. https://doi.org/10.33386/593dp.2025.1-2.2963

(2022). El futuro de la cultura digital de la generación Alfa en México. Economía Creativa, (18), 180-209.https://doi.org/10.46840/ec.2022.18.a6

, , & (2023). Variables associated with the use of screens at the end of early childhood. Pixel-Bit. Revista De Medios Y Educación, 66, 113–136. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.96225

(2003). “Consejos a las Madres”: autoridad, ciencia e ideología en la construcción social de la función materna. Una mirada al pasado. Sarmiento, 7, 61-79. http://hdl.handle.net/2183/7779

& (2021). La Dimensión Socioemocional de la Competencia Digital en el marco de la Ciudadanía Global: Array. Maestro y sociedad, 18(1), 119-131. https://maestroysociedad.uo.edu.cu/index.php/MyS/article/view/5318

, & (2023). Hiperconectados: las niñas, los niños y los adolescentes en las redes sociales. El fenómeno de TikTok. Archivos argentinos de pediatría, 121(4), 1-1. https://doi.org/10.5546/aap.2022-02674

(2020). Sociedad De La Información, Sociedad Digital, Sociedad De Control. Inguruak. Revista Vasca De Sociología Y Ciencia Política, 68, 50-77. https://doi.org/10.18543/inguruak-68-2020-art05

, , , & (2021). Las marcas como eje de socialización de la generación Alpha. Prisma social, (34), 124-145. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/4361

& (2022). La competencia digital del alumnado de Educación Primaria desde la perspectiva de género: conocimientos, actitudes y prácticas. Estudios Sobre Educación, 42, 55-77. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.42.003

(2019). La educación constructivista en la era digital. Revista Tecnología, Ciencia Y Educación, 12, 111–127. https://doi.org/10.51302/tce.2019.244

(2018). Sociedad digital y ciudadanía: un nuevo marco de análisis. Tecnologías digitales para transformar la sociedad, 145-153. http://bit.ly/4jB3cyJ

, , & (2021). Actitudes hacia las TIC y adaptación al aprendizaje virtual en contexto Covid-19, alumnos en Chile que ingresan a la educación superior. Perspectiva Educacional, 60(2), 99-120. http://doi.org/10.4151/07189729-vol.60-iss.2-art.1175

& (2024). Generation Alpha and learning ecosystems: Skill competencies for the next generation. In Fatima Al-Husseiny y Afzal Sayed-Munna (Eds.), Preparing students for the future educational paradigm (pp. 19-46). IGI Global.

(2007). Aspectos psicosociales de las diferencias de género en actitudes hacia las nuevas tecnologías en adolescentes [Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia]. Portal de la Investigación. https://portalcientifico.uned.es/documentos/5f63fc7c29995274fc8e7575

, & (2014). Formación continua y competencia digital docente: el caso de la comunidad de Madrid. Revista Iberoamericana de educación, 65, 91-110. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2690387

(2024). Privacidad, huella digital y derecho a la protección de datos personales en Internet. Revista Internacional de Derechos Humanos, 14(2), 101-150. https://doi.org/10.26422/ridh.2024.1402.san

(2022). La responsabilidad y el cuidado que debe tener la generación alfa. Revista Universitaria, 5(37), 34-35. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11799/112873

(2021). Influencia de la familia y el entorno educativo para la construcción de la identidad en la generación alfa. [Tesis de Licenciatura en Psicopedagogía, Universidad Hemisferios]. https://revistauniversitaria.uaemex.mx/article/view/17996

, , & (2025). Generación Alfa en el Ecuador: Perspectivas y Desafíos en su Futura Empleabilidad: Generation Alpha in Ecuador: Perspectives and Challenges in their Future Employability. Revista Scientific, 10(35), 69-92. https://doi.org/10.29394/Scientific.issn.2542-2987.2025.10.35.3.69-92

& (2023). Generation Alpha media consumption during Covid-19 and teachers’ standpoint. Media and Communication, 11(4), 227-238. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i4.7158

& (2019). Las personas mayores de América Latina en la era digital: superación de la brecha digital. Revista de la CEPAL, (127), 243-268. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6890858

, & (2020). Hábitos de lectura y consumo de información de los adolescentes en el ámbito digital. Investigaciones Sobre Lectura, 13, 72-107. https://doi.org/10.24310/revistaisl.vi13.11116

, & (2024) Adopción del aprendizaje móvil de los nativos digitales en términos del modelo UTAUT-2: un modelo de ecuación estructural. Innoeduca. Revista Internacional de Tecnología e Innovación Educativa, 10(1), 100–123. https://doi.org/10.24310/ijtei.101.2024.17440

, , , & (2024). 12-year-old students of Spain and their digital ecosystem: the cyberculture of the Frontier Collective. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 13, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44322-024-00017-6

, , & (2017). Competencia digital del alumnado de la Universidad Católica de Santiago de Guayaquil. Opción: Revista de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales, 83, 229-251. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/310/31053772008/html/

, , , & del (2017). Uso de las TIC en estudiantes de quinto y sexto grado de educación primaria. Revista Apertura, 9(1), 50-63. http://doi.org/10.18381/Ap.v9n1.913

(2020). Lector, vuelve a casa. Cómo afecta a nuestro cerebro la lectura en pantallas. Deusto.