Metodologías activas y TIC para prevenir el acoso escolar. Principales antecedentes de estudio y contribuciones

Active methodologies and ICT to prevent bullying. Main study background and contributions.

María Pilar Cáceres Reche

Universidad de Granada

Magdalena Ramos Navas-Parejo

Universidad de Granada

María Jesús Santos Villalba

Universidad Internacional de La Rioja

María Rosario Salazar Ruiz

Universidad de Granada

RESUMEN

El acoso escolar es un problema generalizado que ha originado gran alarma social en los últimos años debido a los graves efectos que causa en los niños. En el contexto educativo es una de las expresiones más comunes de la violencia entre compañeros junto con el ciberacoso. El objetivo de esta investigación ha sido analizar la producción científica sobre la prevención del acoso escolar a través de metodologías activas y el uso de las TIC en contextos educativos formales. Este trabajo deriva de un proyecto de investigación financiado a través del Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (FPU18/00676) y es el resultado de un estudio bibliométrico, en el que se han analizado diversos artículos de actualidad mediante la aplicación de diferentes indicadores. Los resultados ponen de manifiesto que la productividad científica sobre esta temática ha proliferado en los últimos años, lo que permite entrever la relevancia concedida a estas cuestiones en la comunidad científica. Entre las conclusiones de este trabajo cabe destacar las ventajas del uso de la gamificación y la utilización de aplicaciones digitales tipo Kahoot o de elaboración de cómics digitales, que permitan a los estudiantes poder simular experiencias que se producirían en el mundo real con el fin de desarrollar nuevas capacidades, autorreflexión crítica y una mayor concienciación del problema. De la misma forma, que resulta imprescindible que los docentes a través de la utilización de estas estrategias didácticas promuevan el protagonismo del alumnado, sus expectativas hacia el aprendizaje, así como la prevención de conductas de intimidación.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Acoso escolar; prevención; metodologías activas; TIC.

ABSTRACT

Bullying is a widespread problem that has caused great social alarm in recent years because of its serious effects on children. In the educational context it is one of the most common expressions of peer violence along with cyber-bullying. The aim of this research has been to analyse the scientific production about the prevention of school bullying through active methodologies and the use of ICTs in formal educational contexts. This study derives from a research project financed through the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (FPU18/00676) and is the result of a bibliometric study, in which various current articles have been analysed through the application of different indicators. The results show that scientific productivity on this subject has proliferated in recent years, which gives a glimpse of the relevance given to these issues in the scientific community. Among the conclusions of this work, the advantages of the use of gamification and the use of digital applications such as Kahoot or digital comics, which allow students to simulate experiences that would occur in the real world in order to develop new skills, critical self-reflection and greater awareness of the problem, should be highlighted. In the same way, it is essential that teachers, through the use of these teaching strategies, promote the students’ protagonism, their expectations towards learning, as well as the prevention of bullying behaviour among peers.

KEYWORDS

Bullying; prevention; active methodologies; ICT.

Introduction

In recent years, school bullying has become a topic of public interest and research because of the short and long-term consequences it has on children’s physical and psychological health (Estévez et al., 2019; Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020; Muñoz-Fernández et al., 2019; Ortega-Barón et al., 2019; Ttofi and Farrington, 2011). Bullying is defined as those behaviours and actions that may involve physical, verbal or non-verbal aggressions, with the clear intention of causing harm. These are perpetrated by one or a group of people and directed at a victim (González-Moreno, Gutiérrez-Rodríguez and Checa-Romero, 2017; Suárez-García, Álvarez-García and Rodríguez, 2020). This intentional harm can be direct, because there is a face-to-face confrontation; indirect, when a third person is involved; or online (cyberbullying).

In the context of this type of violence, several agents are involved, specifically a victim, stalkers, reinforcers and spectators, who intervene directly or indirectly, either by encouraging the stalker, observing and even avoiding the situation that is generated, without paying due attention to the victim (Graham, 2016).

The literature consulted reveals that, despite the fact that cases of school bullying are becoming increasingly prominent in educational centres, it is a phenomenon of profound social alarm that has existed for decades, although its manifestation has now changed, among other reasons, due to the irruption of ICT, which has led to the proliferation of other variants, such as the well-known cyberbullying, which, together with traditional bullying, has negative effects on the academic, emotional and socio-affective lives of the victims (Cerezo et al., 2018; Estévez et al., 2019; Hymel and Swearer, 2015; Ttofi and Farrington, 2011; López-Meneses et al., 2020). Currently, the use of the Internet and digital tools has increased the triggering of bullying behaviors and attitudes at younger ages, due to the easy access that children have to mobile devices and the lack of parental control (Cáceres-Reche et al., 2019; Tabuenca, Sánchez-Peña and Cuetos-Revuelta, 2019).

International survey data indicate that between 30 % and 80 % of school-age youth have experienced some form of bullying or peer violence (Graham, 2016). Similarly, data from the latest UNESCO report (2018) on school violence and bullying shows that 36 % of students admit to having been involved in some form of violence and that 1 in 3 children suffer some form of bullying on one or more days in the last month. All of this generates great concern among families, students, education professionals and society as a whole, seeking to work in a decisive and responsible manner to face a situation that, like this one, is situated in the uneasiness experienced at times in life when determining aspects of personality are forged.

All this concern is justified, taking into account not only the increase in cases of school bullying in recent years, but also by the fact that its effects are not limited to a specific moment (Goldbach, Sterzing and Stuart, 2017), but leave an indelible mark on who we are and how we define ourselves, which, at the same time, is reflected in serious emotional imbalances, emotional deficiencies and problems of social maladjustment.

In this respect, it can be admitted that in this digital and knowledge era, there is a growing interest in promoting preventive and intervention programs for school bullying through the use of ICT, taking advantage of the potential that these offer to increase motivation and willingness to learn among students, thus constituting essential elements to promote their social, emotional and affective well-being (Nocentini, Zambuto and Menesini, 2015). The use of active and innovative methodologies such as gamification, as well as the use of the Internet, social networks or video games are, therefore, tools of inestimable value that can be used with a clear pedagogical purpose, in search of the development of civic and social skills that guarantee the improvement of school harmony.

1. Conceptualization and antecedents of bullying

The phenomenon of school bullying is a type of violence that is increasingly latent in the social context and has great impact on children and adolescents worldwide. However, in recent times, the awareness and sensitization campaigns undertaken have helped to make it visible among the population (González-Moreno et al., 2017). This type of violence takes place in the school context and occurs among students repeatedly and intentionally, with a difference in power between the roles of the bully/s and the harassed, so that the victims feel denigrated, while the bullies seek to make the rest of their classmates feel panic or admiration for them (Mendoza and Maldonado, 2016).

Research into this phenomenon would be initiated by authors such as Olweus (1993), who would focus on clarifying the factors that contribute to an accurate understanding of the processes of intimidation among minors, defining these as “aggressive and intentional acts carried out by a group or an individual repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend himself” (p. 48). This author would highlight the deliberate nature of bullying and the existence of power instability between victim and perpetrator, with situations of violence including those involving physical, verbal and psychological harm. Other authors, however, point out that harassment is more of a phenomenon that involves other students in a group rather than an interaction between harasser and victim (Graham, 2016, Salmivalli, 2010). Along the same lines, it should be noted that, in a situation of bullying, there would be participants other than the perpetrator and the victim, reinforcers, who would encourage the bully to continue, and spectators who are present at the event but rarely come to help the victims. All this can therefore take the format of a direct harm, with face-to-face, indirect confrontation, involving a third person, and online, characterized by the prominence of digital tools, leading to situations of cyberbullying (Ortega, 2010).

With regard to the prevalence of bullying, according to age, Hymel and Swearer (2015) point out that bullying reaches its highest level in secondary education and decreases at the end of it. Similarly, Zych, Ortega-Ruíz and Del Rey (2015), show that the highest prevalence rate is among 11-14 year olds. In terms of gender, most studies highlight the predominant role of men over women as aggressors, while there are no significant differences when it comes to victims (Félix-Mateo, Soriano-Ferrer and Godoy-Mesas, 2009; Olweus, 1993).

In the scientific community there has been a proliferation of meetings in recent years aimed at establishing joint lines of work with which to rigorously profile those variables and factors related to this phenomenon. After extensive processes of deliberation and debate, they reached a common agreement that in the processes of intimidation there is a clear intention to generate harm, in addition to the recurrence of situations of imbalance between harasser and victim, with the consequent gradual loss of power of the victim, which increases in the figure of the aggressor (Menesini and Salmivalli, 2017; Hymel and Swearer, 2015).

In view of the above, it is necessary to establish a profile associated with the various members of a bullying situation. Table 1 shows some of the indicators that allow for a clear identification of the profiles associated with these members.

Table 1. Typical profile of participants in a bullying situation

|

AGGRESSOR |

VICTIM |

OBSERVER |

|

Low self-control and high impulsivity |

Low self-esteem |

Passivity |

|

Lack of empathy |

Some tendency to introversion |

Collaboration |

|

Assumption of leadership role |

Physical or mental disability |

Fear of harassment when reporting |

|

Low academic performance |

Emotional fragility |

Neutrality |

|

Disruptive behavior in the classroom |

Learning disabilities |

Tolerance of bullying |

|

Family breakdown |

Difficulty in establishing interpersonal relationships |

Proclamation of conflict situations |

|

Aggressiveness and intolerance |

Source: Own elaboration from Zych, Ortega y Del Rey (2015).

Most victims of bullying are individuals who lack the assertiveness and complexity to express their feelings (Hodges and Perry, 1999), which makes them seen by the bullies as incapable of defending themselves and of providing solid arguments to give credibility to the bullying situations to which they may be subjected (Nickerson, 2019). Victimization is associated with a range of diverse issues such as depression, anxiety and low self-esteem (Cook et al., 2010; Hawker and Boulton, 2000). Similarly, there is a correlation between victims’ personality characteristics and adverse interpersonal situations, such as low peer acceptance, few friendships and even being part of a problematic peer group (Menesini and Salmivalli, 2017).

In addition, many children who are bullied have a history of being bullied in other places, even from broken homes (Finkelhor, Ormrod and Turner, 2007), lacking the necessary affection and with a great deal of emotional uprootedness. However, other research highlights that victims may also be part of a family context characterized by secure attachment and overprotection (Cook et al., 2010; Lereya, Samara and Wolke, 2013). Victims of bullying also experience greater school difficulties, including poor academic performance and less school participation.

With regard to bullies, there are three subgroups, the intelligent, the popular and the intelligent but unpopular (Rodkin, Espelage and Hanish, 2015). These have feelings of grandiosity and lack of empathy, feel safe when they attack and expect positive results from the aggression, such as approval from the peer group (Menesini and Salmivalli, 2017). Finally, observers in a situation of harassment show a passive and neutral attitude, do not help the victim and do not report the intimidation for fear of being harassed (Zych et al., 2015).

1.1. Types of bullying

In view of the above arguments, it is essential to make a terminological distinction between the different types of bullying (Cerezo et al., 2018). In principle, mention should be made of physical harassment, which is the most frequent and palpable, consisting of the perpetration of blows, beatings and pushing between one or more aggressors to a specific victim. In addition to this, psychological harassment should be highlighted, which causes serious emotional scars, and in which actions that project into discrimination, intimidation and contempt, and even mockery with racist and sexual content, predominate. It is also worth noting the existence of harassment of a sexual nature, accompanied by malicious references to certain intimate parts of the victim’s body. With the intention of isolating the victim from her group of belonging, so-called cases of social harassment may also emerge, with indifference and loneliness as the central axes. Finally, cyber-bullying should be highlighted, in which the use of technological supports such as mobile phones, social networks and e-mails are used as instruments at the service of humiliation and its spread to as many people as possible (Garaigordobil, 2015). Currently, the use of social networks has proliferated to expose the victim or ridicule him/her in front of the world. This type of harassment is characterized by the fact that the harasser has the ability to hide, occurs outside the school and involves other agents as spectators (Cano and Vargas, 2018).

Experts on the subject have tried to delimit cyberbullying by taking into account various elements of reference, so that some authors understand cyberbullying from the perspective of the bullied as a health problem that affects the whole of society, whose solution lies in anticipating it by raising public awareness and offering a system of help to those who suffer it, due to the negative effects on mental health, anxiety and suicidal thoughts (David-Ferdon and Feldman 2007; Deschamps and McNutt, 2016). Other authors postulate that the problem stems from a lack of education in values in schools and focus on teachers to promote prevention and intervention programs in cases of bullying (Willard, 2007; Deschamps and McNutt, 2016). Finally, there are those who focus attention on the harasser as a person who transgresses the norm and point out that the judicial sphere must act and respond to this situation (Cesaroni, Downing and Alvi, 2012).

Both school bullying and cyberbullying present common risk factors and recent research points to the existence of some overlap between the two, since victims of school bullying tend to be bullied through digital devices as well (González-Cabrera et al., 2018; Ortega-Ruíz, Del Rey and Casas, 2016). In this regard, it is necessary to continue along this line of study and promote the development of prevention and intervention programs that respond to the specific needs of victimized youth, taking into account that this is a social problem and it is the responsibility of all agents to respond to it. This approach requires greater public awareness of the serious consequences of harassment and cyber-bullying on the youth population. In this regard, it is essential that teachers be aware of their important work in this context, using innovative and participatory methodologies capable of encouraging students to play a leading role, increasing their expectations of learning and preventing disruptive behaviour, including that associated with the phenomenon of bullying.

2. Active methodologies in the field of education

Currently, the new pedagogical trends tend to leave aside the traditionalist methodologies, to give way to another type of didactic strategies that stand out for being active and innovative, as well as, for favoring participation and autonomous learning. The use of these methodologies is on the rise and they provide a better response to educational demands (Abellán-Toledo and Herrada-Valverde, 2016; Cáceres-Reche et al., 2020; Roque-Herrera et al. 2020) However, according to Zúñiga et al. (2017) the suitability of the method will depend on the educational context in which it is applied and the knowledge of the teaching staff. In addition to being able to discern the most appropriate one to suit the needs of the students and to enable the objectives set to be met. In the same line, De Miguel et al. (2006) defend the use of different methodologies in the teaching-learning process that promote significant learning and the training of the student.

Research into educational innovation therefore seeks to improve certain aspects, leaning towards the inclusion of active or emerging methodologies (Gros and Noguera, 2013) that achieve greater student involvement in their learning. These are educational practices in which the students have a greater role, learning from experimentation and interaction with their peers. The role of the teacher becomes that of a guide in learning, so that the planning part of teaching becomes more relevant than the expository part (Konopka et al., 2015). To all this, we must add the need to use ICT as resources to support teaching, capable of creating new environments, personalizing learning and motivating students. But their use does not always imply innovation and educational improvement; for it to be effective, it must be adjusted to the needs of the classroom and to an appropriate methodology, as well as being used critically and effectively by the educational community (Agulló-Benito, 2016, García-Umaña and Tirado-Morueta, 2018; López-Belmonte et al., 2020).

Innovative methodologies, therefore, involve the set of methods and strategies in which students are the central axis of the teaching process, achieving their active participation and autonomous learning (Moreno, Leiva and Matas, 2016). In this sense, Marín, Ramos and Fernández (2019) state that an effective methodology is one that promotes meaningful and lasting learning, the development of competencies and socialization. These methodologies should have the following characteristics: adaptable to the learning rhythm and to the diversity of each student; that it awakens the interest and motivation of the students; that it allows free decision making by the students; that it promotes socialization and creativity; that it encourages intellectual development and the creation of mental schemes. Examples of this type of teaching strategies are the Flipped Classroom (Moreno-Guerrero et al., 2020), Project Based Learning (Casal et al., 2019), Visual Thinking (Fernández-Fontecha et al., 2019), Problem-Based Learning (Luy-Montejo, 2019), Gamification (Oyola-Moreno, 2019), Design Thinking (Brown and Katz, 2019) and Collaborative Learning (Pinto-Llorente et al., 2020), among others.

However, despite the fact that there is no doubt that these methodologies are the ones that best respond to the students’ educational needs, they have not yet been introduced in the classrooms completely due, mainly, to the resistance of the teachers to carry out this change of role, which implies a new and totally unknown way of carrying out their teaching work. To this lack of experience in the development of these innovative methodologies, we must add the lack of training in them, which in short means the continuation of traditional teaching methods (Valdés-Sánchez and Gutiérrez-Esteban, 2018; Robledo et al., 2015).

2.1 Innovative teaching strategies as bullying prevention tools

Given the existing concern about school bullying, since the 1990s there has been a considerable increase in research on methodological innovation to effectively combat it (Colmenero, 2016). To this end, it is necessary to design anti-bullying methods that can be implemented as soon as possible in educational classrooms from the moment that risk situations may arise (Rubin-Vaughan et al., 2011).

The first bullying prevention programme was carried out by Olweus. Since then, most of the current programs against bullying have been based on it, sharing its fundamental pillars (Smith, Cousins and Stewart, 2005), among others, the existence of an anti-bullying policy, the control of adults within educational centers and the creation of a preventive committee.

According to Smith (2013) the actions carried out to combat school bullying can be classified into three types: prevention, to avoid its appearance; intervention, to eliminate bullying situations once they have occurred and the combination of both.

Among the various methodologies that have been proposed as a form of preventive action and/or intervention against school bullying, the following stand out: the Kiva programme, which emerged in Finland in 2006 with the aim of responding to the phenomenon of bullying through prevention and intervention. To achieve this goal, this program has 10 lessons of 1.5 hours each, where teachers are responsible for transmitting them to their students, encouraging their active participation through debates, teamwork and the use of empathy with those involved in a case of bullying. In addition, families are provided with a manual containing all the information necessary to identify whether their children are involved in a case of harassment (Nocentini and Menesini, 2016). Peer support programs are another anti-bullying strategy created with the aim of preventing these situations, allowing students to increase their social and emotional skills, in order to develop morale, improve the classroom climate and relationships, and break the law of silence that usually exists when a bullying situation occurs. These programmes include school mediation, indirect friends and school assistants (Martín-Criado y Casas, 2019). Finally, there is the instrument called Test Bull-S, which consists of a technique derived from the sociogram, where data is collected through anonymous questions about interpersonal relationships in the classroom, to be analyzed later with software. In this way, it is possible to know the type of relationships that exist between students, the degree of group cohesion and the social role that each one of them plays (Cerezo 2009). This information is very relevant for preventing or detecting risk situations.

However, although various educational strategies have been implemented to prevent school bullying, Macías-Muñoz (2017) points out that there is little teacher training in this area and specifically in the methodologies and strategies best suited to combating it. For their part, students do not have sufficient information on this subject either. This same author also highlights the importance of teachers knowing the basic concepts of bullying, the legislation in force, as well as which professionals are related to school relationships, in addition to the most appropriate techniques and methodologies for working in the classroom. In this way, the use of active methodologies that encourage the participation and integration of students, through cooperative work or with the introduction of conflict resolution techniques, would help to create a good atmosphere in the classroom. Both aspects are key to observe and detect problems of coexistence or suspicious behaviours of conflict in the classroom.

3. The use of ICT to prevent bullying

Today, the students who occupy the classrooms of the 21st century are known as “digital natives”, since they have been born into technology, which has been integrated into their lives, making its use indispensable in society at all levels, including education (Peinado y Mateos, 2016). In this context, ICT can be highly beneficial to learners, in that they promote well-being in many aspects of their lives, add a motivating incentive to learning, and furthermore enrich it (Aznar, 2018).

Fombella-Canal (2018) and other authors such as Vázquez-Cano and López-Meneses (2014) highlight the great advantages that the use of ICT offers to education. Among them, the possibility that students can share information, taking advantage of the technological context in which they are immersed. ICT within the classroom are perceived as an instrument that connects teaching with the real world (Cabero-Almenara, Vázquez-Cano and López-Meneses, 2018). On the other hand, they allow feedback to be obtained, both from other classmates and from the teaching staff, with instantaneous knowledge of errors. These resources also respect the students’ learning rhythms, allow the simulation of experiences that are presented in the real world, developing new capacities, and make it possible to deal with sensitive subjects in a totally anonymous way.

Currently, making use of the potential offered by ICT, they have also been integrated into the field of school bullying prevention, through programs that cover the different devices (Nocentini, Zambuto and Menesini, 2015; Peinado and Mateos, 2016). For example, in Spain there is a telephone number, with a large number of specialists, for reporting school bullying, which was launched in the 2016-2017 academic year. The call to this number leaves no trace. Another Spanish proposal is the Protégete programme, which is an application for smartphones that also allows you to report cases of bullying. Finally, the app Always On has the functions of permanent location of the child and control of incoming and outgoing messages.

On the other hand, video games have been manufactured to be used as anti-bullying resources, which have positioned themselves as one of the most used strategies to fight bullying due to their innovative and motivating character. Within these video games, serious games stand out, which are those that establish goals, which must be reached by the player through his or her own decisions. The aim of these games is for participants to develop social skills that can be used in real life (Guerra, 2017). Some examples of serious games are as follows: Mii-School, which addresses not only the issue of bullying to prevent it, but other types of risky behaviour such as drug use (Cangas, 2018). Fear not, this program recreates a school, in which different characters with different roles appear (bully, spectators, defenders of the bullied or harasser...), the player must choose between the different options, while the program shows him the consequences of each decision taken (Colmenero, 2016).

There are also Digital Game Based Learning on the market. This type of videogame emerged in 2001. Through their participation, different knowledge and social skills are developed to improve relationships between peers (Guerra, 2017). Another category of game is Kahoot, which is an app that, as a contest, allows you to ask questions with several answer options. Its use for the prevention of bullying can be very practical to evaluate and check that the student has correctly integrated all the information received (Glidden, 2019).

Another typology of ICT resources used to prevent school bullying is the digital comic book, which contains a great educational and value transmission capacity, being very motivating and effective in the fight against school bullying.

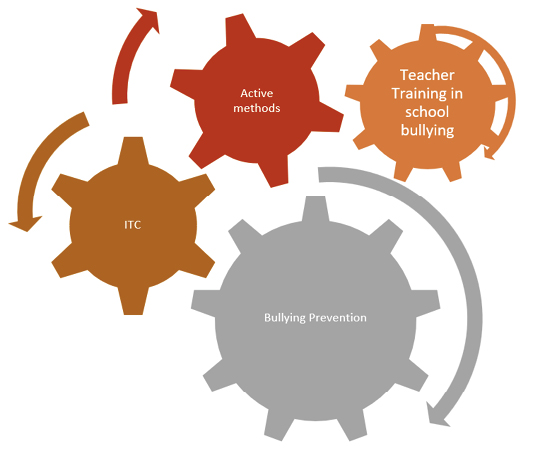

In short, there are many ICT resources that can be used successfully to intervene in this problem, provided that they are linked to an active pedagogical strategy and the teacher has all the necessary information to know how to deal with it. With these ingredients, the gear that is formed, is the perfect set to prevent risk situations in the interpersonal relations of students (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Interconnection and positive feedback relationship between active methodologies, ICT, teacher training and bullying prevention.

Source of own elaboration.

3.1 Digital comics: an ICT resource for the prevention of bullying in formal education

Traditional reading tends to be replaced by other types of activities that have resulted from the development of technology. Many young people now read in digital formats, preferably leaving paper in the background. In this context, the digital comic book emerges as an evolution of the classic comic book that has joined the trend of the society that is increasingly digitized, joining the benefits that reading brings to the interests and motivations of young people towards ICT. In this way, this type of comic has become the main option within the didactic strategies that use reading to inculcate educational values among students (Rina et al., 2020)

Comic books use a graphic-narrative language very suitable for the communication and entertainment of their readers. These aspects, together with the appropriate methodology, can be very useful to facilitate the assimilation of values, in addition to learning educational content (Martínez, 2016). Batanova et al. (2016) highlight the importance of holding a discussion after reading a digital comic book, in order to strengthen the values that they are trying to transmit. In the case of bullying prevention, their study showed that significant conversations and debate on the subject are generated, leading to reflection and the correct assimilation of the message. In this way, it was possible to verify the effectiveness of this medium as an anti-bullying strategy.

Several successful interventions for the prevention of school bullying have been carried out through this ICT strategy. Some examples are the following: Rahimi (2019) used the digital comic strip to create a superheroine called Cipta with which the students felt identified. Cipta uses her superpowers to combat the bullying that takes place in her school. By reading this comic book, he tries to get students to take a stand against bullying by recognizing certain inappropriate situations from the fictional school, which may occur in their real school. Hall (2016), on the other hand, designed a comic book in which, instead of having a hero as the main character, the main characters are made up of a group of heroes and heroines called The Group Hero, who fight against bullying at their school. The purpose of this choice is to give value to diversity.

Teachers have a wide range of creative methodological options to use digital comics in the prevention of school bullying, achieving very positive results that are transmitted outside the classroom, influencing the values of society. One of these options is to give the leading role to the students and allow them, through the service-learning methodology, to make the comic and promote themselves the values of companionship and anti-bullying in the school (Reid and Moses, 2020). This type of creative activities favours both the active participants who edit the comic and reflect on the content they themselves create, developing critical thinking, and the receivers to whom it is addressed, who receive the information from their peers, who have the same concerns and speak the same language (Gómez-Trigueros and Ruiz-Bañuls, 2019)

Today there are many simple digital tools that can be used by students of all ages. In addition, so-called “digital natives” have an innate ability to quickly master any type of device and technological resource. They are usually accustomed to cell phones, photo and video cameras, some write scripts and edit their own videos and stories, using these media as a way of thinking and expression (Sánchez-Carrero, 2011). In addition to their ethical and social value, carrying out this type of activities that use ICT in the classroom also contributes to the development of both digital and communication skills (Moral-Pérez et al., 2019).

When preparing a comic book, you should start by organizing the ideas in it. In this sense, the Storyboard application is a graphic resource used for planning prior to the creation of a comic book. It is frequently applied in the cinema and in the advertising industry (Casas, 2015). In education, it is very useful for understanding an audiovisual narrative (Sánchez-Carrero, 2011).

For comic book designs, it is possible to use video montage, stop-motion animations, photomontages based on graphic elements or even other comics (Gasek, 2017). This type of elaboration develops expression, communication and digital and artistic skills (Althuizen et al., 2016).

There are a number of apps for digital comic book publishing that include a tutorial to facilitate their use (Smith, Shen and Jiang, 2019). These are simple tools with which you can edit comics by choosing templates, including characters, objects, different backgrounds, text balloons and even in some cases your own images. Some examples are the following (Casida and VanderMolen, 2018; Pantaleo, 2019): Storyboardthat, Pixton, Scratch, Moviemarket.

4. Conclusions

Bullying is a phenomenon that continues to be latent in the educational and social reality of our society and its negative effects cause serious harm to the victims who suffer it. In Spain, according to data collected by the NGO Save the Children (2018), among the Spanish population aged 10 to 17, it is clear that 82 % of pre-adolescents/adolescents had observed some kind of violence or humiliation, through teasing, physical and verbal aggression, among others. And that 23 % had participated in some type of violence or humiliation. In view of this situation, we would like to emphasize the necessary involvement of both public and private organizations to make society aware of school bullying. Likewise, the need to make visible the cases of bullying among adults and that there is a deep knowledge of the characteristics of the students involved in these situations together with the variables that make one student more prone to bullying than another is clear.

From the educational context, bullying prevention and intervention programs should be developed that focus not only on the victim but also on the bullies and bystanders, as advocated by Rubin-Vaughan et al. (2011).

In this sense, teachers need to be trained to better understand the dynamics of bullying and to be able to detect cases of bullying both in the classroom and in other spaces. As well as the use of innovative and active methodologies that allow them to respond to the current demands of students and that promote both meaningful learning and socialization among students.

The ICTs used in a coherent manner with any type of active methodology can be very valuable educational resources to combat school bullying from any of its aspects, whether to prevent, intervene or carry out both actions together (Nocentini, Zambuto and Menesini, 2015; Peinado and Mateos, 2016).

Among all the programs and didactic strategies that exist to prevent and intervene in cases of bullying, the digital comic book stands out. It can be a motivating factor when it comes to getting students to get involved in the task of preventing and intervening in possible bullying situations that may occur in their school. Through digital comics, an awareness of this problem can be achieved, which helps to solve it in the educational field, even extrapolating it to the social field. In addition to developing other key competencies such as communication and digital skills (Rina et al., 2020; Martínez, 2016; Batanova et al., 2016).

The limitations found in the realization of this study refer to the lack of bibliography on active methodologies that directly and concretely concern school bullying. Since those analysed do so in a very general way. It was also difficult to find a link between the active methodologies and the ICT resources used jointly to combat bullying.

Finally, we can say that for all the above reasons, we think that it is essential to continue investigating in order to find the most effective way to prevent bullying, to inform and involve the whole educational community in the fight against it, as well as to make available to them the most appropriate resources and methods according to the research and experiences of good practice.

Support

Study funded through the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (FPU18/00676).

REFERENCES

& (2016). Innovación educativa y metodologías activas en educación secundaria: la perspectiva de los docentes de lengua castellana y literatura. Fuentes, 18(1), 65-76.

(2016). Uso de las TIC para la creación de entornos colaborativos e inclusivos En R. Roig-Vila (Ed.). Tecnología, innovación e investigación en los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje. (pp.32-39) Barcelona: Octaedro.

, & (2016). Managerial decision-making in marketing: Matching the demand and supply side of creativity. Journal of Marketing Behavior, 2(3), 129-176. https://doi.org/10.1561/107.00000033

, , & (2018). Descubriendo el entorno desde nuevos enfoques: la realidad aumentada como tecnología emergente en educación. En J. Ruiz-Palmero, E. Sánchez-Rivas y J. Sánchez-Rodríguez (Eds.). Innovación pedagógica sostenible. Málaga: UMA Editorial.

, , , , , & (2016) Examinando conversaciones entre pares de edades cruzadas relevantes para el personaje: ¿Puede una historia digital sobre el acoso escolar promover la comprensión de la humildad por parte de los estudiantes? Investigación en desarrollo humano, 13(2), 111-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1166014

& (2019). Change by design: how design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. New York: HarperBusiness.

, & (2018). Uso de la realidad aumentada como recurso didáctico en la enseñanza universitaria. Formación universitaria, 11(1), 25-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062018000100025

, , & (2019). The phenomenon of cyberbullying in the children and adolescent’s population: A scientometric analysis. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 4(2), 115-128.

, , & (2020). Learning analytics in higher education: a review of impact scientific literature. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, (13), 32-46. https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/IJERI/article/view/4584

, , , & (2018). Análisis de la validez del programa de simulación 3D My-School para la detección de alumnos en riesgo de consumo de drogas y acoso escolar. Universitas Psychologica, 17(2), 186-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.upsy.17-2.avps

& (2018). Actores del acoso escolar. Revista Médica de Risaralda, 24(1), 60-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.22517/25395203.14221

, & (2019). Qué proyectos STEM diseña y qué dificultades expresa el profesorado de secundaria sobre Aprendizaje Basado en Proyectos. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias, 16(2), 220301-220316.

(2015). Técnicas fundamentales para aplicar al dibujo de Cómic digital. Bubok.

& (2018). Uso de la pedagogía Storyboarding para promover el aprendizaje en un programa de educación a distancia. Revista de Educación en Enfermería, 57(5), 319-319.

, , & (2018). Dimensions of parenting styles, social climate, and bullying victims in primary and secondary education. Psicothema, 30(1), 59-65. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.360

, & (2012). Bullying enters the 21st century? Turning a critical eye to cyber-bullying research. Youth Justice, 12(3), 199-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225412459837

(2016). ¿Son eficaces los programas de prevención anti-bullying que utilizan herramientas audiovisuales? Una revisión sistemática. Revista Internacional de apoyo a la inclusión, logopedia, sociedad y multiculturalidad, 3(1), 198-214. https://riai.jimdofree.com/

, , , & (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25, 65–83.

& (2007). Electronic media, violence, and adolescents: An emerging public health problem. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(6), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.020

, , , , & (2006). Metodologías de enseñanza y aprendizaje para el desarrollo de competencias: orientaciones para el profesorado universitario ante el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior. Madrid: Alianza editorial.

& (2016). Cyberbullying: What’s the problem? Canadian Public Administration, 59(1), 45-71. https://doi.org/10.1111/capa.12159

, , & (2019). The Influence of Bullying and Cyberbullying in the Psychological Adjustment of Victims and Aggressors in Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 16(12), 2080. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122080

, & (2009). Descriptive study about school bullying and violence in obligatory education. Escritos de Psicología, 2(2), 43-51.

, , & (2019). A multimodal approach to visual thinking: the scientific sketchnote. Visual Communication, 18(1), 5-29.

, & (2007). Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 7–26.

(2018). Ventajas y amenazas del uso de las TIC en el ámbito educativo. En S. Rappoport (Ed). Debates y prácticas para la mejora de la Calidad de la Educación. (pp. 67-83). Guadalajara: Asociación Investigación, Formación y Desarrollo de Proyectos Educativos.

(2015). Ciberbullying en adolescentes y jóvenes del País Vasco: Cambios con la edad. Anales de Psicología, 31(3), 1069-1076. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.3.179151

& (2014). Efecto del Cyberprogram 2.0 sobre la reducción de la victimización y la mejora de la competencia social en la adolescencia. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 19(2), 289-305.

& (2018). Digital Media Behavior of School Students: Abusive Use of the Internet. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 7(2), 140-147. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2018.7.284

(2017). Frame-by-frame stop motion: the guide to non-puppet photographic animation techniques. Florida, Estados Unidos: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi. org/10.1201/9781315155166

(2019). Alleviating Bullying Behaviors Among Adolescents. (Master’s Theses). California State University. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/504

, & (2017). Challenging Conventions of Bullying Thresholds: Exploring Differences between Low and High Levels of Bully-Only, Victim-Only, and Bully-Victim Roles. Journal of youth and adolescence, 47(3), 586-600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0775-4

& (2019). El cómic como recurso didáctico interdisciplinar. Revista Tebeosfera, 3 (10).

, & (2017). Percepción del maltrato entre iguales en educación infantil y primaria. Revista de Educación, 377, 136-160. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2017-377-356

, , , , & (2018). Relationship between cyberbullying and health-related quality of life in a sample of children and adolescents. Quality of life research, 27(10), 2609-2618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1901-9

(2016). Victims of Bullying in Schools. Journal Theory into Practice, 55, 136-144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1148988

& (2013). Mirando el futuro: Evolución de las tendencias tecnopedagógicas en educación superior. Campus Virtuales, 2(2), 130-140.

(2017). Estudio evaluativo de prevención del acoso escolar con un videojuego (Tesis doctoral). Universidad de Extremadura. http://hdl.handle.net/10662/6030

(2016). El héroe del grupo: un arquetipo cuyo tiempo ha llegado. En S.B., Schafer, (ed.). Explorando el inconsciente colectivo en la era de los medios digitales. (pp. 214-231) Editorial IGI Global.

& (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 441–455.

& (1999). Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 677–685.

& (2015). Four Decades of Research on School Bullying. American Psychologist, 70(4), 293-299. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038928

, & (2015). Active teaching and learning methodologies: some considerations. Creative Education, 6(14), 1536-1545.

, & (2013). Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: A meta-analysis study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37, 1091–1108.

, , & (2020). Proyección pedagógica de la competencia digital docente. El caso de una cooperativa de enseñanza. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, (14), 167-179. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.3844

, , & (2020) Socioeconomic Effects in Cyberbullying: Global Research Trends in the Educational Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 17(12), 4369. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124369

(2019). El Aprendizaje Basado en Problemas (ABP) en el desarrollo de la inteligencia emocional de estudiantes universitarios. Propósitos y Representaciones, 7(2), 353-383.

(2017). Trabajar el bullying con los alumnos del grado de educación primaria: Las metodologías activas, fortalezas y debilidades. En R. Martínez-Medina, R. García-Moris y C. R. García-Ruiz (Eds). Investigación en didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Retos preguntas y líneas de investigación. (pp. 213-222). Universidad de Córdoba.

, & (2019) Metodologías Activas para la Enseñanza Universitaria: Proyecto Enseña+. En F.J., Hinojo Lucena, I. Aznar Díaz y M. P. Cáceres Reche, (Eds.). Avances en recursos TIC e innovación educativa. (pp.101-116). Editorial Dykinson.

& (2019). Evaluación del efecto del programa “Ayuda entre iguales de Córdoba” sobre el fomento de la competencia social y la reducción del Bullying. Aula abierta, 48(2), 221-228. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.48.2.2019.221-228

, , & (2020). Cyberbullying and Social Anxiety: A Latent Class Analysis among Spanish Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 17(2), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020406

& (2017). Acoso escolar y habilidades sociales en alumnado de educación básica. Ciencia ergo-sum, 24(2), 109-116.

& (2017). Bullying in schools: the state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(1), 240-253, https://doi.org.10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740

, & (2019). Evaluación de la potencialidad creativa de aplicaciones móviles creadoras de relatos digitales para Educación Primaria. Ocnos, 18(1), 7-20. https://doi.org/10.18239/ocnos_2019.18.1.1866

, , & (2020). Flipped Learning Approach as Educational Innovation in Water Literacy. Water, 12, 574; https://doi:10.3390/w12020574

, & . (2016). Mobile learning, Gamificación y Realidad Aumentada para la enseñanza-aprendizaje de idiomas. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, (6), 16-34. https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/IJERI/article/view/1709

, , , , & (2019). The Efficacy of the “Dat-e Adolescence” Prevention Program in the Reduction of Dating Violence and Bullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 16(4), 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040527

(2019). Preventing and Intervening with Bullying in Schools: A Framework for Evidence-Based Practice. School Mental Health 11, 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9221-8

& (2016). KiVa anti-bullying program in Italy: Evidence of effectiveness in a randomized control trial. Prevention science, 17(8), 1012-1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0690-z

, & (2015). Anti-bullying programs and Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs): A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.012

(1993). Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do. Oxford: Blackwell.

(2010). Agresividad Injustificada, Bullying y Violencia Escolar. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

, , , , & (2019). Effects of Intervention Program Prev@cib on Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 16(3), 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030408

, & (2016). Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q. Psicología Educativa, 22, 71-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.01.004

(2019). Estrategia de gamificación para la enseñanza de las Normas Internacionales de Información Financiera a los estudiantes de Contaduría de la Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga. EDUNOVATIC2019, 65-69.

(2019). Las posibilidades que dan sentido al componer narrativas gráficas impresas y digitales. Educación 47(4), 437-449. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2018.1494749

& (2016). Aplicaciones móviles contra el acoso escolar. Revista del centro de investigación y estudios gerenciales, 296-314.

, & (2020). La mejora del aprendizaje y el desarrollo de competencias en estudiantes universitarios a través de la colaboración. Revista Lusófona de Educação 45, 257-252. https://doi.org/10.24140/issn.1645-7250.rle45.17

(2019). Usando superpoderes para enfrentarse a la intimidación. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(11), 768. https://doi.org/10.1016/S23524642(19)30301-3

& (2020). Los estudiantes se convierten en autores-ilustradores de cómics: componer con palabras e imágenes en un taller de escritores de cómics de cuarto grado. Profesor de lectura 73(4), 461-472.

, , & (2020). Educación del personaje basada en medios digitales cómicos. Revista Internacional de Tecnologías Móviles Interactivas (iJIM), 14(3), 107-127.

, , & (2015). Percepción de los estudiantes sobre el desarrollo de competencias a través de diferentes metodologías activas. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 33(2), 369-383. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.33.2.201381

, & (2015). A relational framework for understanding bullying: Developmental antecedents and outcomes. American Psychologist, 70(4), 311–321. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0038658

, , & (2019). El uso de la gamificación para el fomento de la educación inclusiva. IJNE: International Journal of New Education, 2(1), 40-59.

, , , & (2020). Active Methodologies in the Training of Future Health Professionals: Academic Goals and Autonomous Learning Strategies. Sustainability, 12, 1485; https://doi:10.3390/su12041485

(2010). Bullying and the peer group: a review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 112–120.

(2011). Introducción a la educación mediática infantil: el diseño del Storyboard. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, (24), 69-83. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2011.24.69-83

Save the Children (2018). Percepciones y vivencias del acoso escolar y el ciberacoso entre la población española de 10 a 17 años. Informe de resultados. https://www.savethechildren.es/sites/default/files/imce/docs/maltrato_contra_infancia.pdf

, & (2019). The Science of Storytelling: Middle Schoolers Comprometiéndose con cuestiones sociocientíficas a través de ciencia ficción multimodal. Voces del Medio, 26(4), 50-55.

(2013). School bullying. Sociología, Problemas e Prácticas, (71), 81-98. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.48.2.2019.221-228

, & (2005). Antibullying interventions in schools: Ingredients of effective programs. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l’éducation, 739-762. https://doi.org/10.2307/4126453

, & (2020). Predictores de ser víctima de acoso escolar en Educación Primaria: una revisión sistemática. Revista de Psicología y Educación, 15(1), 1-15, https://doi.org/10.23923/rpye2020.01.182

, & (2019). El smartphone desde la perspectiva docente: ¿Una herramienta de tutorización o un catalizador de ciberacoso? RED: Revista de Educación a Distancia, 59, 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/red/59/01

& (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review. J Exp Criminol 7, 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1

UNESCO (2018). School violence and bullying: Global status and trends, drivers and consequences. Francia: Unesco. http://www.infocoponline.es/pdf/BULLYING.pdf

., & (2018). COETUM. Proyecto para la creación de un espacio de ágora educativa. Evaluación de un proyecto de innovación para la transformación de la formación inicial del profesorado. Innovación educativa, (28), 189-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.15304/ie.28.5188

& (2014). Los MOOC y la educación superior: la expansión del conocimiento. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 18(1), 3-12.

(2007). The authority and responsibility of school officials in responding to cyberbullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(6), 64-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.013

, , , , , & (2017). Utilización de aprendizaje basado en equipos, como metodología activa de enseñanza de farmacología para estudiantes de Enfermería. Educación Médica Superior, 31(1) 77-88.

, & (2015). Systematic review of theoretical studies on bullying and cyberbullying: facts, knowledge, prevention and intervention. Aggress. Violent Behav. 23, 1–21. https://doi.org.10.1016/j.avb.2015.10.001