Los discursos pro-innovación en la clase de Geografía e Historia. Un análisis lexicométrico

Pro-innovation discourses in Geography and History classes. A lexicometric analysis

Diego Luna Delgado

Universidad de Sevilla

José Antonio Pineda-Alfonso

Universidad de Sevilla

Francisco Florentino García-Pérez

Universidad de Sevilla

Olga Moreno-Fernández

Universidad de Sevilla

RESUMEN

En la actualidad, la innovación educativa se ha convertido en una premisa ineludible para docentes, equipos directivos y familias. Esta aportación se propone conocer mejor la configuración de los discursos pro-innovación desde una perspectiva lexicométrica. Para ello, se aplican diversas estrategias de estadística textual al análisis de un corpus conformado por doce textos verbales, procedentes de cuatro campos discursivos: el marco normativo, el Centro educativo, el Departamento de Ciencias Sociales y la clase de Geografía e Historia en que, finalmente, los discursos pro-innovación devienen prácticas. Los resultados obtenidos, centrados aquí en las asociaciones discursivas de la innovación (colocaciones, combinaciones, concordancias y co-ocurrencias), indican que el significado de la innovación educativa se da por sentado, que solo posee connotaciones positivas y que funciona en sí mismo como argumento para justificar las reformas educativas. Además, se señala que la innovación está especialmente vinculada a las nuevas tecnologías y al vocabulario empresarial. Se concluye con una defensa de la utilidad de las técnicas empleadas, pero también con la advertencia de la necesidad de complementar el análisis realizado con otros tantos de tipo lingüístico e interpretativo.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Innovación educativa; análisis del discurso; análisis cuantitativo; Educación Secundaria.

ABSTRACT

Currently, educational innovation is an unavoidable premise for teachers, school headteachers and families. This contribution aims to provide better understanding of the configuration of pro-innovation discourses from a lexicometric perspective. To this end, we applied various textual statistical strategies to the analysis of a corpus made up of twelve verbal texts from four discursive fields: the education policy, the school, the Social Sciences Department and the Geography and History class in which, finally, pro-innovation discourses become practices. The results obtained, which focus on the discursive associations of innovation (collocations, combinations, concordances and co-occurrences), indicate that the meaning of educational innovation is taken for granted, that it has only positive connotations and that it functions as an argument to justify educational reform. In addition, it is noted that innovation is especially linked to new technologies and business vocabulary. We conclude this paper with a defence of the usefulness of the techniques used, but also with a warning of the need to complement the analysis carried out with other linguistic and interpretative techniques.

KEYWORDS

Educational Innovation; Discourse Analysis; Quantitative Analysis; Secondary School.

1. Introduction

Currently, educational innovation is an unavoidable premise for teachers, school headteachers and families. All of these groups are aware of the urgent need to transform school practices by incorporating new routines and resources that benefit students. Education laws themselves demand the introduction of innovative methodological approaches in the classroom, and schools’ educational projects are increasingly devoting more and more time to explaining their absolute commitment to innovation.

In these circumstances, an increasing number of authors highlight the importance of questioning the effects of innovation (Hall, 2014; Hofman et al., 2013; Martínez Martín & Jolonch i Anglada, 2019; Montanero Fernández, 2019; Pérez Pueyo & Hortgüela Alcalá, 2020; Richter et al., 2019; Serdyukov, 2017), comparing contexts or tracking its impact over a long period of time. However, the experiences that have been studied are still too anecdotal and far removed from everyday reality. In fact, most researchers continue to focus on the isolated, one-off study of innovative measures and projects, uncritically assuming the discursive virtues of innovation.

There are few authors who have been concerned with expressly analysing pro-innovation discourses in relation to school contexts (Cañadel, 2017a, 2017b; Carrier, 2017; Cascón-Pereira et al., 2019; Convery, 2009; Fernández-González & Monarca, 2018; Gramigna, 2010; Moffatt et al., 2016; Pascual, 2019), and we were unable to find any previous study in which lexicometric techniques based on textual statistics were used for this purpose (Breyer, 2018; Breyer & Schemmann, 2018). In any case, the research that employs methods most similar to this methodological approach is not explicitly related to educational innovation, but rather to learning to write (Agrusti, 2014; Iparraguirre & Scheuer, 2016), to innovative experiences that are too specific (Gutiérrez-Lestón et al., 2020) or to university contexts (Zabeli & Kaçaniku, 2021).

This paper defends, on the one hand, the need to critically explore discourse regarding educational innovation, with the aim of understanding the real effects that it is having in practice, and, on the other hand, the usefulness of the lexicometric analysis of texts as a prior, essential and complementary phase to subsequent analyses (linguistic, content, interpretative, etc.).

2. Methodology

The results expressed in this report are part of a broader PhD research project that aimed to understand the impact of pro-innovation discourses in Geography and History classes of a teacher–researcher. In this paper, we focus on a specific moment in an intermediate analytical phase, situated between the preliminary characterisation of the texts used and the qualitative approach. The aim of this study was to make manageable the relatively large corpus, which is organised into four sub-corpora as follows:

Table 1. Composition and organisation of the research corpus.

|

Sub-corpora |

Text |

|

1) Spanish and Andalusian education policies |

1) Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre. |

|

2) Real Decreto 1105/2014, de 26 de diciembre. |

|

|

3) Orden ECD/65/2015, de 21 de enero. |

|

|

4) Decreto 111/2016, de 14 de junio. |

|

|

5) Orden de 14 de julio de 2016. |

|

|

2) School |

6) School Educational Project. |

|

7) School Regulation on Organisation and Operation |

|

|

8) Compilation of materials on the school’s methodology. |

|

|

3) Department of Social Sciences |

9) Geography and History subject guide for students. |

|

10) Annual reports for the academic years 2017-2018 and 2018-2019. |

|

|

4) Geography and History class |

11) Interviews with 44 students (11-15 years old). |

|

12) Teacher–researcher’s diary. |

Source: own elaboration.

The specific aim of the analysis shown here was to identify and graphically represent the discursive associations in which innovation is present in the texts. To this end, we focus on the following four discursive aspects: collocations, combinations, concordances and co-occurrences. The strategies employed were specifically based on statistical resources, typical of the French school of textual data analysis (ADT) (Benzécri, 1973, 1976). This type of technique is considered to be systematic and exhaustive, allowing the identification of units of analysis without the need to adopt a selection criterion beforehand.

Pardo Abril, whose mixed methodology inspired the analysis of our global research, defined “quantitative salience” as a way of representing reality based on “conceptual regularity” (2013, p. 121). In principle, the latter is a symptom of the importance of certain knowledge carried by discourses, manifested by the frequency with which certain discursive units (words, expressions, rhetorical figures, structures, etc.) appear in a text.

The most commonly used statistical unit in this type of strategy is the word as it appears in texts, although in our case, and always in a justified manner, we also opted to lemmatise or regroup certain terms derived from the same root (e.g., by translating all verb forms into the corresponding infinitive) or apply an exclusion list which included all of the terms which were irrelevant from a semantic point of view (e.g., specific articles, conjunctions, typology of paragraphs in a law, numbers, etc.).

The results presented here were specifically derived from the following actions:

Table 2. Actions carried out during the analysis.

|

Aim |

Actions |

|

Identification and graphical representation of associations |

Realisation of the distribution of the occurrences of the lemma innovation in the corpus. |

|

Development of strategic diagrams with the main collocations of the lemma innovation (modifiers, verbs, prepositions, attributes, etc.). |

|

|

Identification of the most frequent contexts and combinations of words derived from the lexemes nov and nuev (new). |

|

|

Identification of the main word combinations derived from the lexemes nov and nuev (new). |

|

|

Identification of the main concordances of the key lexical units. |

|

|

Identification of the main co-occurrences of the key lexical units. |

|

|

Calculation of the coincidence frequencies of the main co-occurrences. |

|

|

Elaboration of a perceptual map showing the degrees of association between the main co-occurrences and the central concept of the research. |

Source: own elaboration.

In order to develop this exploratory–descriptive study, Sketch Engine (SE) was mainly used as a textual analysis and visualisation tool due to its operational convenience and wide range of functionalities, together with MAXQDA (for specific actions, such as the identification of contexts and combinations).

3. Analysis of the results

Next, we proceeded to deconstruct the textual materiality of our corpus by identifying certain connections between the different lexical units identified. These were selected, not only because of their frequency or singularity, but also because they represented or were directly linked to the central concept of the research: educational innovation.

Collocations

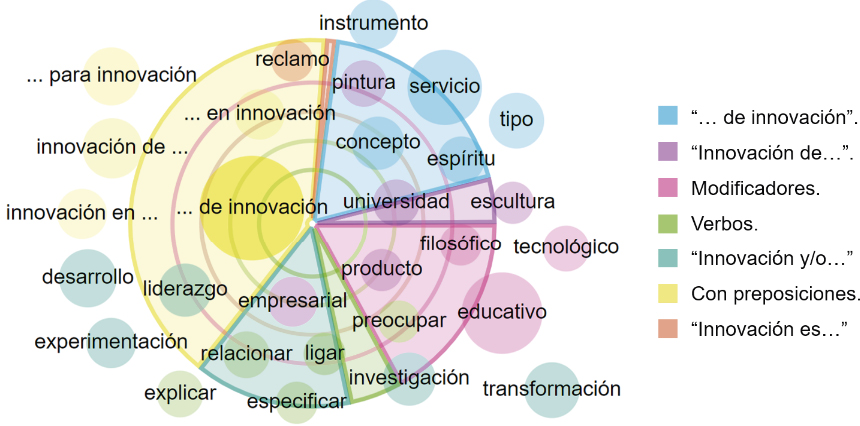

Taking the term innovation, lemmatised as a starting point, the first thing to highlight is the diversity of collocations in which it was present. In the SE Word Sketch functionality, the frequency with which each element or collocation appears in the corpus was represented by the size of its corresponding circle. On the other hand, the position that each occurrence occupied in the target reflected the score obtained according to the possibilities of that same element or collocation appearing exclusively linked to the lemma innovation, in this case (which was represented by the centre of the target), and not to any other.

Figure 1. Strategy diagram with some examples of the main collocations of the lemma innovation in the corpus

Source: own elaboration.

As is shown, the only finding corresponding to the collocation “innovación es…” (“innovation is...”) is: “innovación es un reclamo” (“innovation is a claim”). Without knowing either the text or the context in which it is written, it is quite significant that this single occurrence denotes such a degree of scepticism. Consistent with this lack of clarification, we also observed a certain lack of concern for characterising, defining or specifying the phenomenon by means of modifying adjectives (see Figure 2).

At first glance, this type of result would have led us to intuit that, in the twelve texts of the corpus, the concept of innovation is normally used as a naturalised phenomenon about which no questions can be raised. In fact, the high frequency of the adjective “educativo” (“educational”) would show that, in the majority of cases in which it has been considered appropriate to accompany innovation with an adjective, it was assumed that this adjective, in coherence with the different contexts of the production of the texts, was the appropriate and sufficient one to refer to the meaning that was to be adopted.

Figure 2. Strategy diagram with the main modifiers of the lemma innovation in the corpus

Source: own elaboration.

However, the modifier to which our analysis tool drew the most attention, giving it the highest score of all, was not “educativo” (“educational”), but “empresarial” (“business”). In this sense, we had to note the possible existence of an interesting triangle between innovation, education and business. The adjective “tecnológico” (“technological”) is not surprising, as new ICT-based resources are great allies to new methodologies promoted by pro-innovation discourses. In the case of “filosófico” (“philosophical”), its presence is most likely to be due to an aspect related to the contents or curricular objectives of a Philosophy subject.

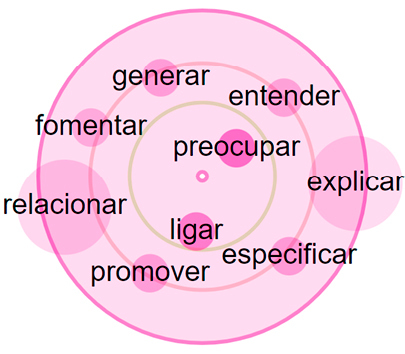

The following figure represents those verbs that take innovation as a direct object. This allows us to know the uses or processes in which innovation is applied or used, although not the intentionality with which this is done. In this respect, the first thing that stands out is the great diversity of actions in which innovation is the protagonist.

Figure 3. Strategy diagram with the main verbs of the corpus that take the lemma innovation as direct object

Source: own elaboration.

Automatically, we can think of several different categories of actions, all of them favourable, in principle, to innovation: nurturing and expanding its development (“preocupar” (“concern”), “generar” (“generate”), “fomentar” (“encourage”), “promover” (“promote”)); linking it to other aspects (“relacionar” (“relate”), “ligar” (“link”)); or trying to clarify its nature or objectives (“especificar” (“specify”), “explicar” (“explain”), “entender” (“understand”)). In terms of our research objectives, the last category is undoubtedly the most interesting of all.

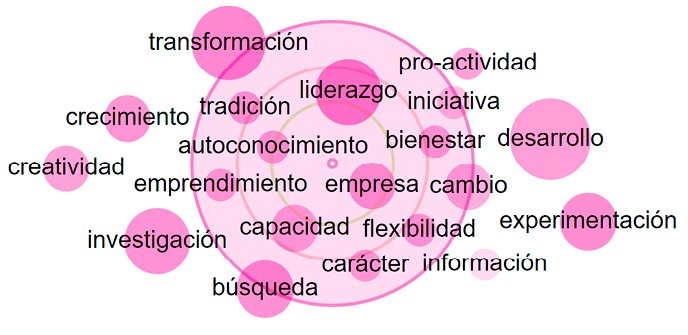

In order to determine which typology of concepts innovation is linked with in our corpus, the search for the collocation “innovation and/or...” was particularly useful. As we can see in Figure 4, the variety of occurrences is quite high, and the meaning they present seems to be in the same line of positivity as the verbs we identified.

Figure 4. Strategy diagram with the typology of occurrences of the collocation “innovation and/or...” in the corpus

Source: own elaboration.

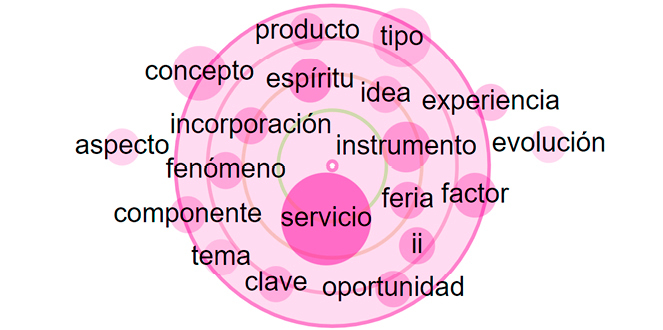

The following diagram focuses on collocations involving the use of a preposition. Of all of them, the most prominent is undoubtedly “... of innovation”, both in terms of frequency and punctuation. This collocation refers to the possible existence of concepts that have features or functions related to the performance of an activity considered innovative.

Figure 5. Strategy diagram with the typology of occurrences of the lemma innovation with prepositions in the corpus

Source: own elaboration.

As shown in the following diagram (Figure 6), our tool explored precisely the typology of terms involved in the previously mentioned collocation. As we can see, the most prominent occurrence is “servicio” (“service”), probably relating to some kind of organisation in charge of promoting innovation. In general, the variety of words is extraordinary, although, with the exception of a couple of specific cases (“feria” (“fair”) and “producto” (“product”)), the common feature is a high level of abstraction (“experiencia” (“experience”), “concepto” (“concept”), “idea” (“idea”), “aspecto” (“aspect”), “fenómeno” (“phenomenon”), “factor” (“factor”), “tema” (“issue”), “espíritu” (“spirit”), etc.), which makes it difficult to understand the message without knowing the context.

Figure 6. Strategy diagram with the typology of occurrences of the collocation “... of innovation” in the corpus

Source: own elaboration.

Combinations

In any case, ideas related to educational innovation would not only be represented by the word innovation, but, in general, by the set of forms derived from the lexemes nov and nuev (new). Once the relatively notable presence of such units in our corpus (798 occurrences in total) was verified, we then focused on them and their possible variants. The following table (3) shows the sixteen most frequent and relevant occurrences in this sense:

Table 3. Most frequent words derived from the lexemes nov and nuev (new)

|

Range |

Word |

Frequency |

Range |

Word |

Frequency |

|

1 |

Nuevas (new) |

187 |

9 |

Novedades (news) |

10 |

|

2 |

Nuevos (new) |

120 |

10 |

Renovación (renewal) |

9 |

|

3 |

Innovación (innovation) |

107 |

11 |

Innovadora (innovative) |

8 |

|

4 |

Nuevo (new) |

92 |

12 |

Innovar (innovate) |

8 |

|

5 |

Nueva (new) |

78 |

13 |

Innovaciones (innovations) |

7 |

|

6 |

Innovadoras (innovative) |

17 |

14 |

Novedad (new) |

6 |

|

7 |

Innovadores (innovative) |

17 |

15 |

Novedosos (new) |

6 |

|

8 |

Innovador (innovative) |

10 |

16 |

Novedoso (new) |

5 |

Source: own elaboration.

In order to gain a better understanding of this varied typology, the next step was to identify the most frequent contexts and combinations of these units. As we can see in the following Table (4), this information is a mere sample of the great semantic and discursive richness that surrounds the innovative phenomenon.

Table 4. Most frequent contexts and combinations of words derived from lexemes nov and nuev (new)

|

Text |

Contexts |

Combinations |

|

1 |

Education; educational institutions; development; society. |

Centre for Innovation and Development in Distance Education (CIDEAD); new patterns of behaviour; new profiles of citizens and workers; new needs; new generations; new technologies. |

|

2 |

Pupils; knowledge; teaching; learning. |

Innovative methodological approaches; new curricular configuration; new approaches to learning and assessment; new learning needs; new knowledge. |

|

3 |

Sense of initiative and entrepreneurship; digital competence. |

Creative and innovative capacity; technological innovations; new knowledge; new skills; new technologies. |

|

4 |

Experimentation; research; teaching; learning. |

Innovative methodological approaches; new approaches to learning and assessment; new knowledge. |

|

5 |

Research; objectives; curriculum; resources. |

Innovative solutions; new organisation of Secondary Education; new technologies; new knowledge. |

|

6 |

Values education; pedagogical model. |

Willingness to innovate; new paradigm. |

|

7 |

– |

– |

|

8 |

Editorial reference; methodology. |

Educational Innovation Service; innovative teaching methods; new learning; new methodologies; something new. |

|

9 |

Contents. |

New topic. |

|

10 |

Methodology; proposals for improvement. |

Innovative activities; more innovative methodologies; new methods of work and study monitoring; new teacher; new awards; new strategies. |

|

11 |

Contents. |

New things; mostly new things; new subjects. |

|

12 |

Methodology; reflection. |

Innovative; innovation; we innovate; innovadulia; new subject; new technologies; new approach; new things. |

Source: own elaboration.

The highlighted combinations present a certain coherence with the context of discursive production from which each of them is derived, although there are others, such as “new technologies”, that span the entire corpus. In fact, a quick overview of the interesting content in the corpus in relation to our research objectives could be made through such combinations.

However, our next aim was to analyse these same combinations or segments more deeply, for which the N-Gramas functionality of SE was used, adopting the following search parameters: segments of between two and six components, containing the characters nov and nuev (new), with nesting of several complementary segments and, finally, with a specific focus on those that should be considered characteristic of this corpus in comparison with the reference corpus proposed by the tool itself, the Spanish Web 2018 (esTenTen18).

Of the 484 total results that our search yielded, only a selection of those segments or combinations that obtained a higher score in the tool is shown below, that is, only those combinations with a better guarantee that they are characteristic of our texts and not of any others.

Table 5. Main word combinations derived from the key lexemes in the corpus

|

Range |

Combination |

Punctuation |

|

1 |

Innovation |

1,61 |

|

2 |

New technologies |

1,57 |

|

3 |

Educational innovation |

1,29 |

|

4 |

Educational Innovation Service |

1,22 |

|

5 |

New elements |

1,22 |

|

6 |

New materials |

1,22 |

|

7 |

New knowledge |

1,2 |

|

8 |

New information and communication technologies |

1,11 |

|

9 |

New strategies |

1,11 |

|

10 |

The news |

1,09 |

Source: own elaboration.

With all of these results, we obtained a first notion of the typology of words that could modify the central concept of the research, offering, at the same time, a first view of the way in which this concept is associated with other existing ideas in the corpus. Herein, we refer to such combinations as key lexical units.

Concordances

In order to analyse the key lexical units in more depth, the next step was to explore their concordances. To elaborate upon the following four tables, one for each discourse field considered in this research, we used the Shuffle lines option in SE, so as not to lose the order or the representative character of the highlighted segments. These results are presented and analysed below.

Table 6. Sample of concordances of key lexical units (I).

|

Previous co-text |

Combination |

Later co-text |

Text |

Location (p.) |

|

Likewise, there is an emphasis on new approaches to learning and evaluation that, in turn, imply changes in the organization and school culture as well as the incorporation of |

innovative methodological approaches. |

Competence-based learning, understood as a combination of knowledge, abilities, skills and attitudes appropriate to the context, promotes autonomy and the involvement of students in their own learning and thus their motivation to learn. |

Decreto 111/2016, de 14 de junio. |

2 |

|

Taking risks, |

being innovative, |

having skills for persuasion, negotiation and strategic thinking are also included among the skills that must be mobilized in youth to help train citizens with entrepreneurship capacity. |

Orden de 14 de julio de 2016. |

180 |

Source: own elaboration.

The concordances in the legislative texts reveal the use of innovation or novelty as a self-justifying argument (reform is necessary because the new circumstances demand it) or as a means of seeking solutions. One of the strongest combinations is undoubtedly “innovative methodological approaches”, which is associated with the development of competences and the multiple virtues that this it is supposed to bring with it. There is also a direct link between innovation and “entrepreneurship”, probably in the context of the general objectives of a subject in the area of Economics.

Table 7. Sample of concordances of key lexical units (II)

|

Previous co-text |

Combination |

Later co-text |

Text |

Location (p.) |

|

(…) thus achieving the development of personal qualities such as creativity, |

willingness to innovate, |

self-confidence, achievement motivation, leadership and resistance to failure. |

Educational Project. |

8 |

|

The teacher, with other colleagues, has for many years been researching and applying the |

new methodologies |

with his students. He has written numerous articles that are enlightening and very practical. |

Compilation of materials… |

14 |

|

In the last few decades we have been enriched by a range of |

innovative teaching methods |

which develop organisational skills and responsibility and which emphasise the analysis and investigation of solutions to real problems (...). |

Compilation of materials… |

29 |

Source: own elaboration.

The School’s Educational Project establishes “willingness to innovate” as an objective to be pursued, which, ultimately, can be linked to what the same text calls the “new paradigm” which it defends. In the compilation of materials on methodology, it is striking that one of the authors of these materials “has been researching and applying the new methodologies for many years”, which may lead one to wonder how many years it takes for a methodology to cease to be new. Finally, such methods, the impacts of which are always presented as positive, are associated with supposed educational enrichment.

Table 8. Sample of concordances of key lexical units (III)

|

Previous co-text |

Combination |

Later co-text |

Text |

Location (p.) |

|

In addition, work has also been carried out occasionally with applications such as Kahoot, Quizizz, KeyNote or Picollage (...). |

The great novelty |

and, at the same time, the great failure of this course in terms of tools has been the digital blog. |

Annual reports… |

10 |

|

Despite this, it has been possible to reverse this negative situation in the 3rd quarter, due to the special emphasis placed on working with maps, using |

all kinds of innovative activities, |

which sought no other objective than arousing the curiosity and motivation of students to study these contents. |

Annual reports… |

18 |

Source: own elaboration.

In the annual reports, we found the greatest semantic deployment of the third sub-corpus, for example, when referring to elements that are “new” compared to the previous year, although one of them was also a “great failure”. It is interesting that the concept of “innovative activities” is linked to the objective of “arousing the curiosity and motivation of pupils”. Finally, there is a call for “new strategies”, a lexical unit intended to represent the formulas for solving a given problem.

Table 9. Sample of concordances of key lexical units (IV)

|

Previous co-text |

Combination |

Later co-text |

Text |

Location (p.) |

|

What we mean by innovate or what we innovate for on this site is another matter.... I do not think my colleagues and I are clear about that, although I would dare to talk about |

innovadulia, |

as a kind of obsession to innovate without thinking about the implications or consequences. |

Teacher-researcher’s diary. |

3 |

|

My concept of innovation is almost a reaction to the imposed concept of innovation that predominates at the School. For me, |

to innovate |

is to make each class a different adventure, surprising students with new ways of doing things. |

Teacher-researcher’s diary. |

28 |

Source: own elaboration.

The most interesting concordances in the fourth and last sub-corpus were mainly found in the diary of the teacher–researcher. The neologism “innovadulia” appears there, the co-text of which confirms its critical charge. In addition, the expression “new things” appears, which very effectively represents the great quantity and variety of elements that can be new in a certain moment. Finally, we found a definition of the verb “to innovate” based on personal experience, in perfect coherence with the context in which it is produced.

Co-occurrences

The last step involved determining which specific concepts innovation is preferentially associated with in the corpus. To do this, we chose to calculate the frequencies of coincidence or co-occurrence between, on the one hand, the typology of key lexical units (those combinations formed by words derived from the key lexemes) and, on the other hand, the present words in the respective concordances of each of these same units.

To develop this task, the Collocations option, within the Concordance functionality of SE, was used, selecting a range of between -10 and 10 words around each searched unit. As statistical measures, T-score and logDice were used. The former basically reflects the degree of certainty with which we can affirm that there is an association between the searched units and the terms that accompany them, that is, that the co-occurrences found are not by chance. logDice indicates the typicity of the collocations formed from such co-occurrences, relating the frequencies of the unit searched in the entire collocation it is a part of.

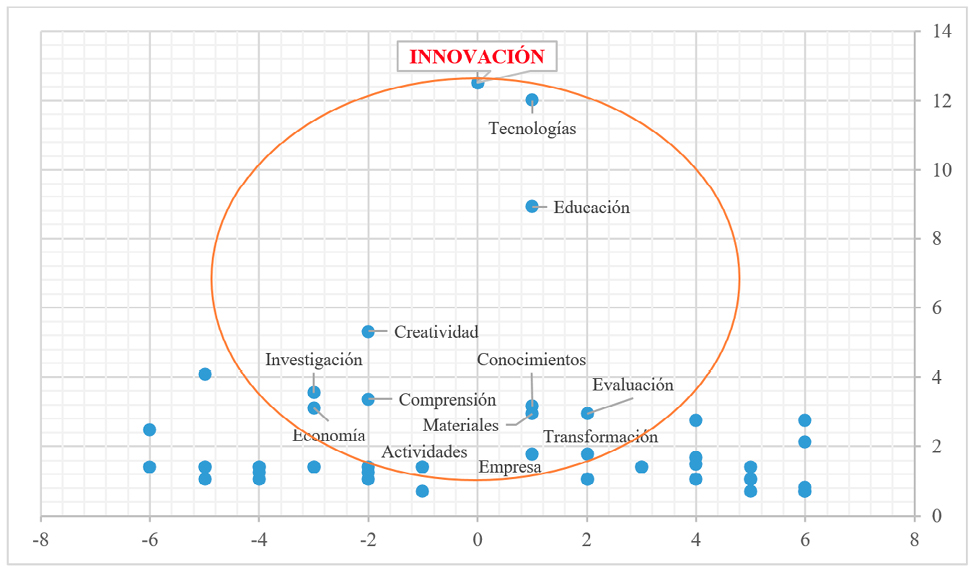

With such data, a perceptual map was then drawn up to represent the degree of association between the main co-occurrences and the possible ideas related to innovation. To do this, we accounted for the degree of co-occurrence and the position of the co-occurrences in the co-text. In the case of several lemmatised words, the position of the word with the highest percentage of co-occurrence was taken.

Figure 7. Perceptual plane representing the degrees of association between the main co-occurrences and the central concept of the research

Source: own elaboration.

As can be seen, two co-occurrences were particularly close to the concept of “innovación” (“innovation”): “tecnologías” (“technologies”) and “educación” (“education”). This confirms, on the one hand, the great prominence of technologies in pro-innovation discourses and, on the other, the suitability of these texts for use in understanding the impact of educational innovation. In somewhat more distant positions, we found concepts which, in line with what we have seen in previous sections, represent aspects of both the educational and economic spheres (“investigación” (“research”), “creatividad” (“creativity”), “actividades” (“activities”), “transformación” (“transformation”), etc.). In fact, some of the lemmas in this select group are “economía” (“economics”) and “empresa” (“business”).

4. Discussion and conclusions

The lexicometric analysis carried out here allowed us to make more manageable our large corpus, but also to gain a better understanding of it in terms of the discursive associations established between innovation and other concepts. In methodological terms, we can confirm the usefulness of the techniques employed, both for investigating our corpus and for applying them to all types of educational discourse (Breyer, 2018; Breyer & Schemmann, 2018). On this occasion, the results obtained were progressively transformed, in parallel to the transformation of the units of analysis themselves (Pardo Abril, 2013): from innovation as a simple lemma implied in multiple collocations, passing through the main combinations of key lexemes and their corresponding concordances, to the deconstruction of the concordances of the latter in co-occurrences that reflect the special typology of concepts that accompany innovation in the texts.

In this sense, we must confirm the possibility of getting very interesting data, without the need to adopt a previous selection criterion, due to the lexicometric approach. The wide range of functionalities offered by SE or MAXQDA was key to develop this inductive procedure. Thanks to the strategic diagrams created with SE, we could easily visualise some crucial aspects, eg., the great variety of collocations or actions in which innovation is implied. In addition, another of SE’s main contributions was its capacity, not only to calculate word frequencies, but to identify key units, through the application of statistical measures that allowed us to compare our corpus with a reference corpus. This last task is fundamental in terms of applying critical discourse analysis in any research.

In general, all the discursive associations analysed allow us to characterise educational innovation in the following ways: 1) according to an obvious lack of clarification and characterising, its meaning is taken for granted (Carrier, 2017) and works as an argument to justify changes (Moffatt et al., 2016; Serdyukov, 2017) such as changes in LOMCE educational reform in Spain (Cañadel, 2017b); 2) in its main collocations, it coincides with particularly abstract words (“experience”, “concept”, “idea”, “aspect”, “phenomenon”, etc.) (Cascón-Pereira et al., 2019); 3) its co-occurrences and concordances only suggest positive connotations (“leadership”, “well-being”, “growth”, “development”, etc.); 4) it is closely linked to business, entrepreneurship and economics, as even its psychological implications reflect (“self-confidence, achievement motivation, leadership and resistance to failure”) (Cañadel, 2017a; Fernández-González & Monarca, 2018); and 5) it appears closely linked to “new technologies” (the second main word combination derived from the key lexemes) and not particularly linked to new methodologies (Martínez Martín & Jolonch i Anglada, 2019; Montanero Fernández, 2019; Richter et al., 2019).

These findings demonstrate the great benefit of the lexicometric analysis: to identify patterns in the macrostructure of discourses, through a number of texts, that would not be visible when analysing smaller corpora or single texts. From a proper preliminar analysis to familiarise ourselves with the corpus, as well as to recognise the demands of the topic itself, the lexicometric analysis can be a profitable addition to the great spectrum of methodological approaches in education research. Even though it belongs to linguistic sciences, the present study shows the potential of this kind of analysis to approach every kind of education discourses, regardless of its production context (policies, schools, departments, classes…).

Finally, it should be noted that our exploratory analysis must now be complemented by a linguistic and interpretative approach of the data (Hall, 2014; Hofman et al., 2013). While the benefits of the lexicometric analysis are various, the implicit knowledge, sarcasm or, in general, qualitative relation between words, can’t be identified by it. In a new analytical phase, the actors, contexts, themes and topics reflected in the texts must be addressed, as well as the grammatical strategies through which meanings are established. This will determine the confirmation or rejection of the conclusions set out here, as well as the real intentionalities that we can associate with the subjects associated to one discursive field or another. In this way, we can ultimately come to an understanding of the different cultural models, regimes and power structures (Pascual, 2019), which are guarantors of the meanings carried by texts.

Notes

This article is part of the doctoral thesis “The impact of innovative teaching in Secondary Education. Geography and History class as a case study”.

REFERENCES

(2014). Prime analisis lessicometriche sull’esperimento Nulla dies sine linea experiment. CADMO, 2, 13-40. https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/3014911

(1973). L’Analyse des Données. Tomo I: La Taxinomie. Dunod.

(1976). L’Analyse des Données. Tomo II: L’analyse des Correspondances. Dunod.

(2018). Patterns of difference in understandings of equity and social justice in adult education policies: Comparing national reports in international contexts by a lexicometric analysis. Studies in the Education of Adults, 50(2), 152-166. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2018.1522943

, & (2018). Comparing national adult education policies on a global level. An exploration of patterns of difference and similarity in international policy contexts by method of lexicometric analysis. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 37(6), 749-762. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2018.1553211

(2017a). La innovación educativa: ¿Un paso más hacia la educación neoliberal? Nuestra bandera: revista de debate político, 236, 86-95.

(2017b). Las trampas de la “Nueva” Innovación educativa. El Viejo Topo, 354-355, 80-87.

(2017). How educational ideas catch on: the promotion of popular education innovations and the role of evidence. Educational Research, 59(2), 228-240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2017.1310418

, , & (2019). An exploration of the meanings of innovation held by students, teachers and SMEs in Spain. Journal of Vocational Education y Training, 71(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2019.1575894

(2009). The pedagogy of the impressed: how teachers become victims of technological vision. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 15(1), 25-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600802661303

, & (2018). Los sentidos de la rendición de cuentas en el discurso educativo. Perfiles latinoamericanos, 26(51), 379-401. https://doi.org/10.18504/pl2651-015-2018

(2010). La paradoja de la innovación inmóvil: reflexiones críticas sobre la mitología educativa de la agenda de Lisboa. Revista española de educación comparada, 16, 43-73. http://revistas.uned.es/index.php/REEC/article/view/7524

, , , & (2020). Innovación de educación emocional en el ocio educativo: el Método La Granja. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 38(2), 495-513. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/rie.405721

(2014). Evaluando los procesos de cambio. Midiendo el grado de implementación (constructos, métodos e implicaciones). Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 12(4e), 99-130. https://revistas.uam.es/index.php/reice/article/view/2839/3056

, , , & (2013). Educational Innovation, Quality, and Effects: An Exploration of Innovations and Their Effects in Secondary Education. Educational Policy, 27(6), 843-866. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904811429288

, & (2016). “¿Cómo hablan y escriben mis alumnos?”: Concepciones lingüístico-educativas de docentes de nivel primario. Estudios pedagógicos, 42(1), 139-158. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052016000100009

Martínez Martín, M., & Jolonch i Anglada, A. (Coords.) (2019). Las paradojas de la innovación educativa. Horsori.

, , , , , & (2016). “Essential cogs in the innovation machine”: The discourse of innovation in Ontario educational reform. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 38(4), 317-340. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2016.1203680

(2019). Métodos pedagógicos emergentes para un nuevo siglo. ¿Qué hay realmente de innovación? Teoría de la educación, 31(1), 5-34. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.19758

(2013). Cómo hacer análisis crítico del discurso. Una perspectiva latinoamericana. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

(2019). Innovación educativa: un proceso construido sobre relaciones de poder. Revista Educación, Política y Sociedad, 4(2), 9-30. https://revistas.uam.es/reps/article/view/12205

, & (2020). ¿Y si toda la innovación no es positiva en Educación Física? Reflexiones y consideraciones prácticas. RETOS. Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 37, 639-647. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/7243323.pdf

, , & (2019). Responsible innovation and education: integrating values and technology in the classroom. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 6(1), 98-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2018.1510713

(2017). Innovation in education: what works, what doesn’t, and what to do about it? Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 10(1), 4-33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-10-2016-0007

, & (2021). Policy Analysis for Mapping the Discourse of Inclusion in Higher Education System in Kosovo. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 19(2), 452-483. http://www.jceps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/19-2-17-fjok.pdf