Desarrollo de la empatía y valores éticos a través de los juegos de rol como innovación para la educación en valores

Development of empathy and ethical values through role-playing games as innovation for education in values

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

Ricardo Moreno-Rodríguez

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

Nerea Felgueras Custodio

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

RESUMEN

Para algunos autores, el desarrollo de la empatía es un aspecto central del desarrollo de los valores éticos. Los juegos de rol pueden ser el vehículo ideal para trasladar aprendizajes de la ficción a la realidad. El presente estudio analiza de forma exploratoria y descriptiva las puntuaciones obtenidas en el Test de Empatía Cognitiva y Afectiva (TECA) de una muestra total de 208 participantes. Aunque no se han hallado grandes diferencias entre las personas que habían participado con anterioridad en juegos de rol y las que no lo habían hecho, si se detecta una tendencia a obtener puntuaciones medias superiores a las que lanza el TECA a través de sus baremos.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Juegos de rol; Empatía; Valores éticos; Aprendizaje.

ABSTRACT

For some authors, the development of empathy is a core aspect of ethical value development. Role-playing games can be the ideal vehicle to transfer learning from fiction to reality. The present study analyzes the scores obtained in the Test of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (TCAE) of a total sample of 208 participants in an exploratory and descriptive way. Although no major differences were found between those who had previously participated in role-playing games and those who had not, there was a tendency of obtaining higher average scores than those obtained by the TCAE through its scales.

KEYWORDS

Role;playing games; Empathy; Ethical values; Learning.

1. Introduction

Empathy, if defined by integrative models, is a multidimensional construct, in which both affective and cognitive aspects are circumscribed (Arán et al., 2021). It involves skills that allow individuals to know how other people feel, understand their intentions, discern their thoughts or predict their behaviors. In other words, empathy is the tool that enables effective interaction with the social world (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004). Some authors speak of empathy as an affective response to the emotions of others, highlighting the importance of the affective component (Bryant, 1982; Hoffman, 1982). On the other hand, it would make no sense to speak of empathy without a cognitive system that regulates learning, thoughts and the manipulation of information received through the senses. According to Kerem et al. (2001), the cognitive component would act as a prelude to the affective component. López-León & Gómez (2018) highlight that, for students, having empathic or non-empathic experiences with their teachers has a direct impact on their motivation.

Some authors link the development of empathy with moral and ethical development (Hauser, 2008; Prinz, 2011a, 2011b; Rifkin, 2010, p. 174; Slote, 2007). However, while some posit that it has a secondary role, others argue that its role is determinant. Altuna (2018) raises a question describing the conflict that arises from assuming empathy as a direct road to ethics: how could empathy fulfill the moral philosophical criterion of impartiality, if it’s characterized by biases of partiality? Certainly, doubts arise about empathy’s role in moral development, but not about the relationship between the two concepts.

On the other hand, it seems that strategies such as repeatedly telling students which actions are “good” or “bad” are insufficient per se. There is a need to explore other educational avenues, focused on empirical exploration and development of moral values based on empathy. Gamification of learning may be an optimal strategy for this, as it empowers students to develop analytical thinking strategies, promotes motivation towards one’s own learning, and increases memorization and information retention skills (Chandran et al., 2020). In the specific case of role-playing games, endless possibilities for learning and teaching arise. They can be used in a similar way to what would be a reinforcement program based on token economy through the obtaining of experience points that serve to improve the capabilities and skills of the character that each player plays, thus achieving a greater probability of success. In addition, in role-playing games the consequences of the characters’ actions can be related, which will have repercussions in the narrative fiction. In the role-playing world there are several famous examples that many game directors use to make players question the morality and repercussions of their actions. One of the best known is the Orc Baby Dilemma, where, in very short, once the players have successfully overcome all the obstacles and defeated all the enemies, they reach the last chamber of the dungeon, where they find themselves with the only presence of an orc baby and must decide what to do with it (Sesenra, 2019).

As with most games, role-playing games have their own characteristics that make them a useful tool for education and learning. Like other types of games, role-playing games entail their own rules, fun, entertainment, and imagination, among others (Brell, 2006). It is common for role-players to conceive this type of games as a refuge, even functioning as a source of emotional catharsis, with the benefits and risks that this entails, which are mentioned in almost all the manuals that can be found on the market. The role-playing game acts as a figurative mirror that shows what one is and what one is not simultaneously from a fictitious prism, fed directly by reality (Romero, 2019).

It is easy to find very diverse definitions about role-playing games, since practically all game manuals usually begin with an explanatory section where they try to explain what this type of games consists of. For example, Hite (2018) defines role-playing games as:

One of the most recent forms of artistic expression of storytelling, where players tell or perform stories for an audience composed of themselves, under the guidance of the rules or logic of the game but limited only by their imagination. (p. 40).

On the other hand, Gil et al. (2019) define them as:

An adventure board game without a board, where one player assumes the role of game director and the others become adventurers. The game director narrates a story as if it were the script of a movie, describing the locations and situations that occur, while the players act freely based on the rules contained in the manual. (p. 8).

Some definitions are even given in a humorous way, making a simple circular definition: “what you are holding in your hands right now is a role-playing game” (Pamundi & Piñol, 2020, 7), adding that it is easier to play a role-playing game than to explain what it consists of.

There are several precedents for the use of role-playing games -even in their “live” variant or in the form of video games- within the field of education. Simkins & Steinkruehler (2008) revealed that role-playing games were frequently associated with improved student learning and tended to stimulate their curiosity, as well as being successfully used as a support to promote scientific development and in subjects such as mathematics, history (Sánchez et al., 2022), reasoning and literacy. Barbosa & Trindade (2020) describe the activities carried out by the Osterskov Efterskole, in the words of its director, Mads Lunau:

We use “learning games” to teach the curriculum. Once a week, we present students with a variety of universes and let them play with that universe. [...] Within that universe, students interact with each other and experience the limits of the constructed “reality”. They are presented with problems, cases, tasks, and knowledge that are relevant to their roles and to the (game) universe they are trying to master.

Storm & Jones (2021) conducted an investigation focused on the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons within an after-school space oriented towards people belonging to the LGTBIQ+ collective. In this case, the participants were involved in a deconstructive critique with perspectives towards the future, building a utopian world through their narration. They explored the injustice of the present time, while imagining a radically different, more just and inclusive future.

Da Silva (2020) designed a role-playing video game where he aims to raise awareness of the implications of “invisible” disabilities and other medical conditions in everyday life. They have even been used within therapeutic intervention as a tool to increase users’ social connection (Abbott et al., 2021). Anderson (2019) has used role-playing games in the educational ambit within the branch of philosophy. In addition, he provides a brief guide to introduce philosophy into games -and not the other way around-, serving as an additional technique that aims to improve the impact of philosophy in everyday life. García-Fernández et al. (2017), presented an innovative educational proposal based on gamification and mobile applications with the aim of helping students to create collaborative learning contexts and improve content retention, in addition to promoting a safe and assertive school climate (Miranda de la Lama & Daturi, 2021).

The use of role-playing games for educational purposes is part of game-based learning as an active methodology that uses the game as a vehicle and tool for learning. Since participation in play is consubstantial to the human being as an occupational being, the use of role-playing games to educate in values allows addressing affective, motivational, cognitive and motor aspects.

2. Method

Participants.

First, we proceed to eliminate all outliers, that is to say, all those cases in which their Z scores are more than three standard deviations away from the mean. The purpose of this exclusion of cases is to prevent extreme scores from biasing subsequent statistical analyses.

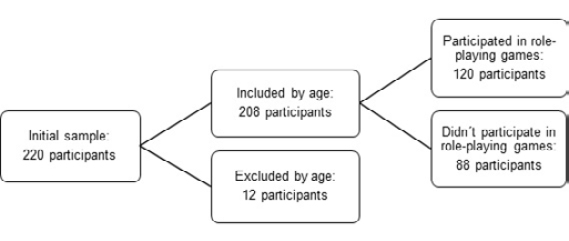

Thereafter, the initial sample consists of a total of 220 participants, selected through a non-probability snowball sampling strategy. From this initial sample, twelve cases were excluded because they did not meet the minimum age requirement of 18 years, resulting in a sample of 208 participants (N=208).

The participants ranged from 20 to 53 years of age, divided into three age groups. Between 20 and 29 years of age, there were 98 participants, between 30 and 39 years of age, there were 50 participants, and between 40 years of age and older, there were 60 participants. The average age was 32.25. Moreover, 111 participants were women, while 97 were men.

Figure 1 Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of participants.

Own work.

Most of the participants have higher education. Of the total number of participants with higher education, 102 participants have received a university education, 37 have a university master’s degree and another five have a doctorate. On the other hand, six participants have completed secondary education, 24 have a bachelor’s degree and 34 have completed vocational training.

Of the remaining 208 participants, a filter was also established among those who had participated in a role-playing session: 88 had never participated, while 120 had done so on at least one occasion. Of the participants who had played role-playing games, the majority were men (87), compared to the number of women who had played role-playing games (33), while 78 women and 10 men had never participated in role-playing games.

In relation to the degree of experience that the participants have in role-playing games, most of the sample have been playing for more than five years (78), while some had started playing less than six months ago (5), between six months and one year (11), between one and two years (8) or between 2 and 5 years (18).

Regarding the frequency of participation in role-playing sessions, 50 participants played role-playing games infrequently, 25 played frequently and 35 played very frequently. Some of the participants admitted having given up the hobby (10).

Table 1 Frecuency table. Description of the selected sample.

|

Category |

Group |

No. of participants |

|

Age |

20 – 29 years |

98 |

|

30 – 29 years |

50 |

|

|

40 years and older |

60 |

|

|

Gender |

Woman |

111 |

|

Man |

97 |

|

|

Educational level |

Secondary Education |

6 |

|

Baccalaureate |

24 |

|

|

Vocational education |

34 |

|

|

University education |

102 |

|

|

University master’s degree |

37 |

|

|

Doctorate |

5 |

|

|

Experience level |

Less than 6 months |

20 |

|

Between 6 months and 1 year |

18 |

|

|

Between 1 and 2 years |

15 |

|

|

Between 2 and 5 years |

75 |

|

|

More than 5 years |

3 |

|

|

Playing frequency |

No longer participates |

10 |

|

Infrequent |

50 |

|

|

Frequent |

25 |

|

|

Very frequent |

35 |

Own work.

Instrument

For the purpose of collecting information, the Cognitive and Affective Empathy Test (CAET) was used. This is a standardized test composed of four scales that measure both the cognitive and affective aspects of empathy. On the one hand, the cognitive dimension is assessed through the Perspective Adoption (PA) and Emotional Understanding (EU) scales. On the other hand, the affective dimension includes the Empathic Stress (ES) and Empathic Joy (EJ) scales. The test has 33 items in total, which are divided into the four scales mentioned above, with 8 items per scale, except for the EU scale, which has 9 items (López-Pérez et al., 2008, 8, 17).

In the statistical justification section, the CAET itself indicates that the psychometric tests were carried out with a heterogeneous sample of adults (N=380), aged between 16 and 66 years, 58 % of whom were women and 42 % men. The Shapiro-Wilk statistic was used to assess the distribution of the scores on the scales. The results show that a normal distribution can be assumed for the Perspective Adoption and Empathic Stress scales, but not for the Emotional Understanding and Empathic Joy scales, due to the existence of a significant negative asymmetry. (López-Pérez et al., 2008, 15).

To assess reliability, the authors of the test (López-Pérez et al., 2008, 17) used two procedures. On the one hand, the reliability coefficient was calculated by the method of two halves, obtaining an rxx=.86. This shows that 86 % of the variance is due to the variability shown by the participants in the trait evaluated, and, therefore, that only 14 % can be explained by measurement errors. On the other hand, Cronbach’s internal consistency coefficient was calculated, which yielded a=.86 for the total scores and, in any case, above.7 for each of the scales. This indicates that the internal consistency of the CAET is good, since it exceeds.8 (Nunnally, 1978).

With respect to content validity, the CAET is based on a solid theoretical foundation, taking into account all the aspects that define empathy, through the scales and dimensions described above.

Initially, 48 items were elaborated, of which 15 were discarded for presenting factorial validity difficulties. For the factorial validity analysis, a principal component extraction and an oblique rotation (Oblimin) were performed. These analyses confirmed the existence of four factors that coincide with each of the scales, saturating many of the items with values above.6 and.7. Only one item had a saturation higher than.3 in two factors, and there is none that saturates below in its own factor.

Finally, López-Pérez et al. (2008) conducted a correlational analysis with other questionnaires that measure the same construct. They obtained a=.804 with the Questionaire Measure of Emotional Empathy (QMEE) and a=.786 with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI).

When it comes to gender, significant differences between men and women were detected in the development of the CAET, so the test itself provides gender-differentiated scales for each of the four scales of which it is composed. This does not occur with other factors such as, for example, age.

Procedure

For the preparation of this study, the following hypotheses are proposed:

•H1: People who have played role-playing games obtain a higher mean score in their rating than the results given by the CAET.

•H2: People who have played role-playing games score higher on the different scales that make up the CAET than those who have not played role-playing games.

The present study attempts to investigate whether role-playing games naturally help the development of empathy, i.e., without specific intervention applied for this purpose, resulting in an exploratory study that aims to investigate the current state of the question. To this end, we have tried to obtain as many participants as possible, and thus compare their scores obtained in the CAET. It is proposed that the more time a person has spent participating in role-playing games, the higher his or her percentile will be within the scale provided by the test itself. It is estimated that the total duration of the questionnaire, including the application instructions and the sociodemographic questionnaire necessary for the preparation of this study, is around 15 minutes.

The questionnaire was transferred to digital format in order to reach the largest possible number of participants. It was distributed through social networks and groups specialized in role-playing games, as well as publishers specialized in the publication of role-playing games and the group of participants of the educational innovation project carried out in collaboration with the City Council of Alcorcón, through the Center for Studies and Didactic Resources for the Support of People with Disabilities. Participants were also asked to share the link to the questionnaire with people they knew and were close to, in order to start the snowball sampling process. It should be noted that participation was voluntary and completely anonymous, in addition to being a study prior to the development of a specific intervention within the framework of the aforementioned educational innovation project.

3. Results

First, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov nonparametric statistical test is performed to assess whether the distribution of the results in each of the scales can be considered to be in accordance with the normal distribution. In all the scales there is a significance of less than.05, so the results cannot be considered to have a normal distribution. The CAET itself reports that normal distribution cannot be assumed for the Emotional Understanding and Empathic Joy scales.

The different analyses are performed using non-parametric tests, as the normal distribution of the scores is ruled out. A preliminary exploration of the existence of significant differences for each of the scales with respect to each of the sociodemographic variables is carried out. For this purpose, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H statistic (Ostertagová et al., 2014) is used.

In the gender variable, there are significant differences in all scales except for Perspective Adoption. Women score higher and the standard deviation is lower, so it can be said that the responses are more homogeneous. The same is true for the total scores.

Regarding the different age ranges, in the scales Emotional Understanding, Empathic Joy and Perspective Adoption, there are significant differences between participants aged 20 to 29 years and the rest of the age ranges, but not between participants aged 30 to 39 years and 40 years and over (p=. 66). The highest mean scores are found in the 20-29 years age group (EU=36.7, EJ=36.9 y PA=33.9), and the responses are more homogeneous, while in the 30-39 years age group they are very heterogeneous. In the Empathic Stress scale, there are significant differences between the three age groups, with, once again, the scores of participants aged 20 to 29 years being higher (ES=29.1). In the total scores, there are also significant differences between all the groups, although on this occasion the responses of the group between 20 and 29 years of age are more heterogeneous with respect to the other groups.

The mean scores of people who had never played role-playing games were higher in all scales except for Perspective Adoption, although no significant differences were found except for the Empathic Stress scale and the total scores.

Regarding variables such as educational level, the results would not be reliable due to the large relative sample difference between the different groups. The groups composed of participants who had completed secondary education (6 cases) and doctorate (5 cases) generate significant biases, so these cases are not taken into account for the Kruskal-Wallis H-test. Significant differences are found in the Empathic Stress scale and in the total scores. In both cases, the differences are found in the scores of the participants who had completed vocational training ((ES=23.2 and TS=127.4), the mean score being lower than those of the participants who had completed high school and university education, who presented very similar intergroup means. Those who had completed high school had a mean score of 25.1 in empathic stress and 131.9 in total scores, while those who had completed university education showed means of 27.1 and 131.8 respectively.

On the other hand, taking into consideration only those who had participated in role-playing sessions (N=120), comparative analyses were carried out taking into consideration two variables: the experience level of the participants and the playing frequency. Regarding the experience level, most of the participants had extensive experience with role-playing games (78 participants), having started the hobby more than 5 years ago. Thus, very minority groups emerge for the rest of the categories that make up this variable. As a result, the results are widely biased and, therefore, are not taken into consideration.

With regard to the playing frequency, only those participants who continue to participate in role-playing sessions are taken into account (N=110). Significant differences were found in the Empathic Stress (p=.024) and Perspective Adoption (p=.029) scales. In the case of Empathic Stress, differences were found between participants who participated infrequently and those who participated very frequently (p=.008), with higher mean scores in the “infrequent” group. However, the opposite is true for Perspective Adoption. The relationship of inequality occurs in the same way, between the groups that participate “infrequently” and “very frequently” (p=.012), but on this occasion the mean scores of the participants who play role-playing games more frequently are higher.

Finally, in order to contrast whether H1 is fulfilled, a comparison is made between the mean scores of the participants who have ever played role-playing games and the mean scores obtained in the CAET rating, both for each of the scales and for the total scores, as shown in the following tabla 2.

Tabla 2 Comparison of averages and standard deviations.

|

CAET (N=380) |

Participants (N=120) |

||||

|

Average |

Standard deviations |

Average |

Standard deviations |

||

|

PA |

29 |

4,43 |

34 |

3,15 |

|

|

EU |

30 |

5,06 |

35,7 |

4,49 |

|

|

ES |

24 |

5,69 |

23,9 |

6,78 |

|

|

EJ |

32 |

4,24 |

36 |

3,07 |

|

|

Total Scores |

115 |

13,98 |

129,7 |

10,62 |

|

Own work.

4. Conclusions

The main objective of the present work is to assess whether role-playing games naturally have any influence on the development of empathy and, therefore, of ethical values. In general terms, the data obtained do not indicate significant differences in this aspect; nevertheless, these results open the way to new experimental designs of a different nature. However, the mean scores obtained are higher in the case of the participants than the means obtained in the TECA scoring process in three of the four scales. These scales are Perspective Adoption, Emotional Understanding and Empathic Joy, as well as in the total scores.

Contrasts were also made according to different sociodemographic variables. Based on the different age ranges, younger participants showed higher scores on all scales, so it can be stated that, in this case, younger participants have a higher development of their empathic skills. It is possible that these data are affected by other sociocultural factors, moreover, it seems that the current trend and evolution of role-playing games seems to be heading towards a much more inclusive environment (Williams et al., 2018).

Regarding the degree of prior experience, the data are underdetermined, discrete, and seemingly contradictory. There are significant differences between the groups participating very frequently with the group participating infrequently on the Empathic Stress and Perspective Adoption scales, given so that in the infrequent participation group the ES scale scores are higher, while in the case of the PA scale, the scores were higher in the very frequent participation group. Unfortunately, there were important biases due to the distribution of the participants in the different subgroups of the variable Degree of experience, since the great majority of the participants were veterans who had been participating in the hobby for more than 5 years, with extremely few cases of participants from any of the other groups. Because of this, this variable was disregarded and was not taken into consideration for the present study.

5. Discussion

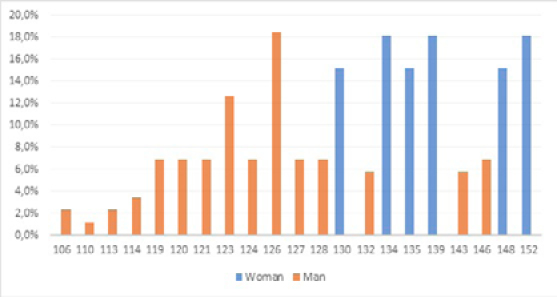

Taking the data obtained into consideration, it can be affirmed that H1 is fulfilled, since the mean scores obtained by people who play role-playing games are slightly higher than those obtained by the CAET. In any case, it seems that the differences are very discrete. In addition, there are different variables that may have influenced the results. Namely, as explained below, the gender variable has had a strong effect on the results (Figure 2), as it does in some age groups. In this aspect, it seems that younger participants have obtained higher scores in the CAET, a result that may be affected by the sociocultural context in which they have grown up and in which the participants are immersed or because social desirability has had a greater influence on their responses. Future research designs may take into consideration adding questionnaires such as the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale to assess the sincerity of the responses (Ávila & Tomé, 1989; Ferrando & Chico 2000; Gutiérrez et al., 2016).

Figure 2 Distribution of total scores according to gender.

Own work.

On the other hand, the fact that most of the participants are women, but, nevertheless, in proportion, participation in this type of games is mostly male, seems to indicate that there is a gender-based participation gap. This gap is also similarly evident in other ludic domains (García, 2017; Williams et al., 2018), as in the case of video games, where streamers and female players are much more pressured and receive more insults and harassment from spectators than in the case of male gamers (Afonso & Aguilera, 2021; Rubio & Cabañes, 2012). Fortunately, and according to Lynne (2010) there are more and more scenarios in tabletop role-playing games that can be used to teach participants about respect for diversity, opening channels of understanding between people with different identities, including aspects such as ethnicity, race, history, nationality, gender, and sexual orientation.

Returning to the results obtained, no significant differences could be found between people who had never played role-playing games and those who had, except for the Empathic Stress scale and the total scores, which were higher in the group of people who had never played role-playing games. H2 is therefore rejected. It is relevant to take into account that most of the sample were women, being in turn most of the sample who had never played role-playing games. This fact may explain why the scores are higher among the group of participants who had never played role-playing games, since, according to the CAET (López-Pérez et al., 2008), the mean scores obtained by women are higher than those obtained by men in all scales.

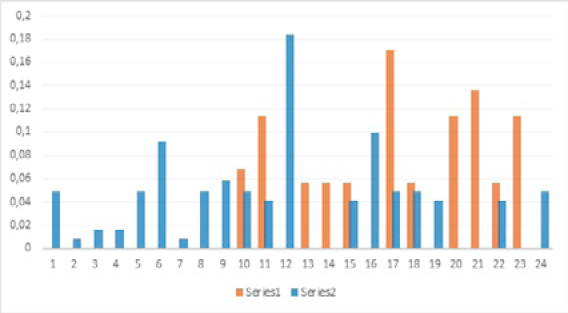

It is striking that the empathic stress scale is the only one in which there are significant differences. Figure shows how people who had never participated in role-playing sessions obtained higher scores than those who had. According to Lazarus & Folkman (1986), both problem-solving strategies and support seeking are part of successful coping with anxiety. In the functional substratum of role-playing games, the game director proposes problematic situations that the players must solve through decision-making processes within the fiction, achieving a group narrative development that is often reinforced by the search for support among the played characters themselves. This fact may constitute the beginning of a future line of research based on the stress management capacity of role-players by itself, using for this purpose other standardized tests such as the Coping Responses Inventory – Adult Form (CRI-A), developed by Moos and adapted by Kirchner & Forns (2010) or the Escalas de Apreciación del Estrés (EAE), by Fernández-Seara & Mielgo (2017).

Figure 3 Direct Empathic stress scores as a function of previous experience with role-playing games.

Own work

The possibility of replicating the study with a larger sample also arises, since it is necessary to avoid possible biases that could not be controlled, derived from groups that are too unequal and with too few participants. To this end, studies of different types (exploratory, descriptive and correlational, both cross-sectional and longitudinal) are also needed, in more controlled environments and with specific interventions aimed at critical ages for the development of empathy and ethical values.

Although the results of the research do not indicate the existence of significant differences in the development of empathy based on participation in role-playing sessions, there are many avenues to be explored in future research. Perhaps the most obvious is the design of a specific intervention aimed at children and adolescents based on a child-oriented role-playing game such as Tiny Dungeons (Bahr, 2018) or Magissa (Patsaki & Reyes, 2016), so that we can assess whether there is indeed a learning factor with respect to empathy and moral and ethical development.

Finally, the development of a possible assessment tool can be taken into consideration. This is not the first time that games have been used as a tool to assess performance in various categories. For example, the Weschler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-V) approaches some of its tests as games (cubes, visual puzzles, picture span or similarity). In this way, they are more attractive and are not too tedious for users (Amador & Forns, 2019).

REFERENCES

, & (2021). Table-top role-playing games as a therapeutic intervention with adults to increase social connection. Social Work with Groups, 45(1), 16-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2021.1932014

& (2021). Desigualdades en el mundo de los videojuegos desde la perspectiva de los jugadores y las jugadoras. Investigaciones feministas, 12(2), 677-689. https://doi.org/10.5209/infe.60947

(2018). Empatía y moralidad: las dimensiones psicológicas y filosóficas de una relación compleja. Revista de Filosofía, 43(2), 245-262. https://doi.org/10.5209/RESF.62029

& (2019). La escala de inteligencia de Wechsler para niños, quinta edición: WISC-V. Documento de trabajo. https://bit.ly/3xhM9vI

, & (2021). Aproximación neuropsicológica al constructo de empatía: aspectos cognitivos y neuroanatómicos. Cuadernos de Neuropsicología / Panamerican Journal of Neuropsychology, 6(1), 63-83. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4396/439643203006.pdf

& (1989). Evaluación de la deseabilidad social y correlatos defensivos emocionales. Adaptación castellana de la Escala de Crowne y Marlowe. En A. Echevarría y D. Páez (Eds.), Emociones: perspectivas psicosociales (505-514). Fundamentos.

(2018). Tiny Dungeon. Akuma Studio.

& (2020). Reflexões acerca do roleplaying game (RPG) na educação: potencialidade cognitiva. Revista Multidebates, 4(2), 114-124. http://revista.faculdadeitop.edu.br/index.php/revista/article/view/244

& (2004). The empathy Quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 163-175. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:JADD.0000022607.19833.00

(2006). Juegos de rol. Educación social: Revista de intervención socioeducativa, 33, 104-113. https://bit.ly/3oss9Rc

(1982). An index of empathy for children and adolescents. Child development, 53, 413-425. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128984

, , , , & (2020). Using entertainment media to teach undergraduate psychiatry: Perspectives on the need and models of innovation. Arch Med Health Sci, 8(1), 125-132. https://www.amhsjournal.org/text.asp?2020/8/1/125/287367

(2020). Designing a Digital Roleplaying Game to foster awareness of hidden disabilities. International Journal of Designs for Learning, 11(2), 55-63. https://doi.org/10.14434/ijdl.v11i2.27257

& (2017). Escalas de Apreciación del Estrés. TEA ediciones.

& (2000). Adaptación y análisis psicométrico de la escala de deseabilidad social de Marlowe y Crowne. Psicothema, 12, 383-389. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72712309.pdf

(2017). Privilege, Power and Dungeons & Dragons: How systems shape racial and gender identities in tabletop role-playing games. Mind, Culture and Activity, 24(3), 232-246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2017.1293691

, , , & (2017). Gamificación y aplicaciones móviles para emprender: una propuesta educativa en la enseñanza superior. International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation (IJERI), 8, 248-259. https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/IJERI/article/view/2434

, & (2019). Peacemaker. Nosolorol.

, , , & (2016). La escala de Deseabilidad Social de Marlowe-Crowne: baremos para la población general española y desarrollo de una versión breve. Anales de psicología, 32(1), 206-217. https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.1.185471

(2008). La mente moral. Paidós.

(2018). Vampiro: la mascarada (5 ed.). Nosolorol.

(1982). The measurement of empathy. En Izard C.E., Measuring Emotions in Infants and Children (pp. 279-296). Cambridge University Press.

, & (2001). The experience of Empathy in everyday relationships: cognitive and affective elements. Journal of social and personal relationships, 18(5), 709-729. https://doi.org/10.1177/026540750118500

& (1986). Estrés y procesos cognitivos. Martínez Roca

& (2018). Entendiendo la empatía en la educación del diseño. International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation (IJERI), 10, 51-63. https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/IJERI/article/download/3456/2742/0

, & (2008). Test de Empatía Cognitiva y Afectiva (TECA). TEA ediciones.

& (2021). La empatía y su trascendencia en la educación. La colmena, 112, 51-62. https://doi.org/10.36677/lacolmena.v0i112.15772.

(2010). CRI-A. Inventario de Respuestas de Afrontamiento. TEA ediciones.

(1978). Psychometric Theory. McGraw Hill.

, & (2014). Methodology and Application of the Kruskal-Wallis Test. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 611, 115-120. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.611.115

& (2020). Fanhunter. Devir.

& (2016). Magissa, rol para niños. Nosolorol.

(2011a). Is empathy necessary for morality?, en Coplan, A. y Goldie, P. (eds.), Empathy: Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives. Oxford University Press.

(2011b). Against empathy. Southern Journal of Philosophy, 49(1), 214-233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-6962.2011.00069.x

(2010). La civilización empática: la carrera hacia una conciencia global en un mundo en crisis. Paidós.

& (2012). El sexo de los píxeles. Del yo-mujer al yo-tecnológico. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 98, 150-166. https://www.injuve.es/sites/default/files/Revista98_11.pdf

, & (2022). Iberia: Un juego de rol para una didáctica de la historia antigua significativa e innovadora. El futuro del pasado, 13, 641-669. https://doi.org/10.14201/fdp.27394.

[Sirio Sesenra] (14 de noviembre de 2019). El dilema del bebé orco [Video]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/0A3Yw4qle1o

(2007). Moral sentimentalism. Oxford University Press.

& . (2021). Queering critical literacies: disidentifications and queer futurity in an afterschool storytelling and roleplaying game. English teaching: Practice & Critique, 20(4), 534-548. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-10-2020-0131

, , & (2018). Sociology and Role-Playing Games. Routledge.