Mindfulness (MBI) en la formación continua y evaluación de la transferencia en la empresa pública

Mindfulness (MBI) in continuous training and evaluation of the transfer in the public sector

Laura Molina-García

Universidad de Almería

César Bernal-Bravo

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2802-1618

Antonio Hilario Martín-Padilla

Universidad Pablo de Olavide

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0136-2735

RESUMEN

En este artículo de investigación, se presentan los resultados de transferencia al puesto de trabajo de la formación Mindfulness: Cultivando la atención plena, recibida por parte personas trabajadoras de la Diputación de Sevilla. La acción formativa es recibida como formación continua dentro de los planes de formación continua de la Diputación de Sevilla.

Concretamente la acción formativa presencial, es una Intervención Basada en el Mindfulness (MBI): Mindfulness: cultivando la atención plena, con una duración de 28 horas.

De esta intervención MBI se han analizado varios parámetros, uno de ellos la transferencia de los conocimientos adquiridos a la práctica profesional y personal.

Los datos analizados desprenden resultados positivos en todas las personas participantes, por lo que se puede afirmar que la formación en mindfulness supone una mejora en capacidades como la paciencia, resiliencia, comunicación, resolución de problemas, reducción del estrés, entre otras cuestiones a destacar en el clima empresarial y en la salud mental de las personas que la componen.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Mindfulness; formación continua; transferencia al puesto de trabajo.

ABSTRACT

This research article presents the results of transfer to the workplace of the training received by workers of the Diputación de Sevilla. The training action is received as continuous training within the continuous training plans of the Diputación de Sevilla. Specifically, the face-to-face training action is a Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI): Mindfulness: cultivating full attention, with a duration of 28 hours.

Several parameters of this MBI intervention have been analyzed, one of them the transfer of the knowledge acquired to professional and personal practice.

The analyzed data show positive results in all the participants, so it can be affirmed that mindfulness training supposes an improvement in capacities such as patience, resilience, communication, problem solving, stress reduction, among other issues to be highlighted in the business climate and the mental health of the people who make it up.

KEYWORDS

Mindfulness; continuous training; transfer to the workplace.

1. Introducción

The search for a fulfilling life, well-being, and happiness is a constant in the lives of most people. However, due to external factors, many people find themselves needing to respond, with utmost speed, to the multitude of stimuli that come with, at the very least, a competitive attitude. The obstacles of daily life and the rejection that generates fear or aversion add to this difficult situation. In this scenario, our survival system frequently generates a stress reaction over extended periods of time, thus hindering the management of emotions and, with it, our actions (Marina, 2006; Segal, 2006). In recent years, the enormous increase in research and studies analyzing the effectiveness of mindfulness should be highlighted. The information that arises is that people who practice mindfulness obtain psychosomatic improvements, stress reduction, recovery from depressive states, dependencies, and eating disorders, optimize emotional management, quality in interpersonal relationships, and a sense of well-being (Hervás et al., 2016; Garrote-Caparros et al., 2021). From this perspective, developing emotional management is necessary to generate emotional processes that are suitable for the demands of our personal and work environments (Villalba, 2019; López-Martínez, 2021). When we are unable to create a space between emotions, and it seems like they dominate us or throw us off balance, on other occasions, they cause unfortunate actions that end up becoming new sources of suffering (Villalba, 2019; Hanh, 2020; Lyddy et al., 2021).

To the problems that occur in the personal sphere, those generated in other environments such as the workplace are added; an environment dominated by competitiveness, multitasking, or the demands of speed and immediacy typical of the technological era (Germer, 2011). This scenario creates a breeding ground for diseases and disorders associated with stress, depression, or anxiety. As Sainz Martínez (2017) describes, the business and organizational environment is increasingly changing, which leads to higher demands on the working population, who are required to be more effective, efficient, and profitable in the work they perform.

Furthermore, all these problems usually have a close link to the processes of interpersonal relationships that occur in work environments, which further contributes to a worsening of physical and mental health problems. Resolving this situation is not an easy task when, at the same time, the figures related to work absenteeism resulting from burnout syndrome, workplace harassment, or stress-related disorders are increasingly high. Therefore, companies and organizations, through movements such as CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility), and motivated by the need to comply with laws on occupational risk prevention, have been introducing the attention to the prevention of psychosocial risks into their organizational structures. This movement is contributing to developing a spirit of seeking physical, psychological, and social well-being from human resources (García del Junco et al., 2018). It is necessary, in short, for people to learn to optimize emotional management as a tool that helps reduce stress and improve the perception of well-being or happiness, which serves to promote personal and professional empowerment (Simón, 2011). Therefore, developing an efficient attentional capacity can be of great use when facing everyday events, as efficiency implies achieving any goal with the least expenditure of energy and time (Sesha, 2019). On the other hand, learning methods and strategies for conscious attention facilitates self-observation and acceptance of reality, promoting effective management of emotions, recurrent thoughts, impulses, etc., contributing to more equanimous mental and emotional states (Steyn, 2013).

To achieve the development of mindful attention, the increasingly accepted and scientifically proven option is through mindfulness practice through meditation. And this is where continuous training within companies and organizations finds in mindfulness a resource of demonstrated effectiveness in situations such as those mentioned above (De la Cuesta, 2004). In fact, mindfulness has strongly emerged in the continuous training of organizations as a result of its demonstrated effectiveness in other contexts. In this sense, more and more organizations are incorporating the implementation of mindfulness in their training processes, creating spaces where the integration of this practice in work contexts can be generated (Glomb et al., 2011). Large corporations such as Apple, Google, Facebook, Procter & Gamble, Nike, Ikea, Ford, Twitter, Starbucks, Heineken, Xerox, etc., and even Spanish companies such as Endesa, Repsol, Mahou, San Miguel, Naturgy, or Altadis, have included mindfulness practice in their continuous training. This trend has also been present in the public sector, in agencies and councils of different autonomous communities such as Andalusia, Aragon, the Basque Country or the Valencian Community, among others (García-Campayo and Demarzo, 2018).

The reason for this is the strong evidence of the results that mindfulness practice has on people’s mental processes. After all, it involves deploying attention and concentration, promoting the tackling of obstacles and difficult situations, finding creative solutions and responses, improving the development of attitudes that generate better intra and interpersonal relationships (one of the main causes of conflicts, poor communication, and stress in the work context), or increasing understanding, equanimity, and compassion (Karlin, 2018; Shapiro and Carlson, 2014; The Mindfulness Initiative, 2018). Ultimately, all these skills favor personal and professional empowerment, giving the feeling of having a fuller life (Steyn, 2013).

Studies evaluate how mindfulness practice is highly effective in reducing common problems in the business and organizational environment such as burnout, stress, anxiety, and significantly improving intra and interpersonal relationships, empathetic and compassionate abilities (Chiesa and Serretti, 2009; Farb et al., 2010).

With mindfulness training and practice, a series of attitudes are developed that, when contextualized in the business world, offer great benefits in the medium and long term. In this regard, García-Campayo and Demarzo (2018) describe the advantages of mindfulness training for workers and the company. Specifically, regarding the benefits that mindfulness can produce in the workplace, these authors describe that:

•Attracts and retains talent.

•Increases the involvement of workers.

•Increases commitment and sense of belonging.

•Increases job satisfaction of workers.

•Increases work performance.

•Creates more committed, creative, and productive work teams.

•Reduces work-related illnesses.

•Generates an optimal climate for innovation.

•Improves communication and work environment in the company.

•Reduces absenteeism and “fake work attendance”.

For the working population that is trained in mindfulness, changes are also generated that facilitate their personal and professional development, given the training and its practice. Ultimately, when a company invests in a training process and offers spaces for mindfulness practice, it is possible to develop many important capacities such as attention, concentration, resilience, or acceptance of reality, which promote personal and professional empowerment. All of this suggests that mindfulness plays a role in developing high potential and effectiveness in organizational processes (Hyland et al., 2015; Karlin, 2018).

Continuous training is therefore a strategic element of vital importance for organizations. By implementing continuous and systematic training actions, the aim is to respond to the training needs of the workforce, modifying or developing their competencies. In this sense, many resources are allocated to this type of action, making it necessary to establish channels that allow us to know both the level of knowledge acquisition and the satisfaction of the people receiving the training, as well as how that training contributes to the development of the organization and whether the investments made have been effective and efficient (Pineda-Herrero and Quesada-Pallarés, 2013).

The effectiveness of training should be evaluated from different perspectives. In this sense, it is necessary to know to what extent the training actions carried out have improved the competitiveness of the organization, whether they have facilitated the adaptation of human resources to the changes that may have occurred, and whether they have facilitated the personal and professional development of the participating individuals (Pineda et al., 2020). Ultimately, evaluating the effectiveness of training actions implies (González Ortiz de Zárate et al., 2017):

•Evaluating the learning of the participating individuals.

•Evaluating the profitability of the training by analyzing the relationship between training costs and benefits.

•Evaluating the transfer of the training received.

Therefore, implementing a system for evaluating the transfer of training will increase its impact and provide relevant information to the responsible bodies of the organization to explain the development of training, its strengths, and the improvements that can be made. Thus, we can find two types of transfer evaluation (González-Ortiz et al., 2017; Pineda et al., 2020):

•Direct evaluation of transfer. It focuses on measuring the degree to which the knowledge and competencies acquired during training are put into practice in the workplace, understanding such evaluation as a result of the training. Indicators used include changes that occur in relation to the performance, satisfaction, or job security of those who participate in the training action.

•Indirect evaluation of transfer. It consists of detecting and evaluating those factors that have a significant impact on transfer. Thus, information can be obtained about the aspects that hinder or facilitate transfer in an organization, predict the degree of transfer that will occur, and make the necessary adjustments to improve it.

This type of evaluation involves using instruments created specifically for each training action, collecting observable evidence of application, analyzing the perceptions of the workers themselves, their superiors, and colleagues, and conducting pre- and post-training competency analyses (Pineda-Herrero et al., 2014). Indirect evaluation is shown to be a more plausible alternative, as it takes into account the factors that hinder and facilitate the application of learning to the workplace (Pineda-Herrero and Quesada-Pallarés, 2013). This type of evaluation is less costly, both in terms of effort and economics (Tomás-Folch and Durán-Bellonch, 2017).

In this sense, Pineda, Quesada, and Ciraso (2020) have developed the FET Model (Factors for Indirect Evaluation of Transfer), which is adapted to the Spanish context. It is table 1.

Table 1. Modelo FET de factores para la evaluación de la transferencia

|

Dimensions |

Factors |

|

Participant Dimension |

– Satisfaction with training – Motivation to transfer – Internal locus of control – |

|

Work Environment Dimension |

– Accountability for Implementation – Environment possibilities for implementation – Support to transfer – |

|

Training dimension |

– Orientation to the needs of the work place |

Source: Pineda-Herrero et al., (2020)

The FET Model integrates different theories related to training transfer and proposes two instruments: the FET Questionnaire and the CdE Questionnaire. The FET Questionnaire consists of 42 items, which are rated using a 5-point Likert scale. It gathers the participant’s perception of the model’s factors discussed earlier and provides a diagnosis of the transfer that has occurred. The Efficacy Questionnaire (CdE) aims to identify the degree to which participants have applied what they have learned on the job. If the FET Questionnaire has been administered previously, it also allows for an assessment of the predictive capacity of the factors. This questionnaire is composed of 6 items, rated using a 5-point Likert scale, and analyzes only the efficacy factor (Pineda-Herrero et al., 2020).

The FET Model suggests that, in the public administration, effective training is one that (Pineda-Herrero et al., 2014):

•Is linked to job needs.

•Generates a positive reaction from participants towards the training, its design, and the trainer’s role.

•Is considered by the participant as depending directly on their own person (internal locus of control) for the successful application of learned competencies.

•Takes place in a work environment that enables transfer.

•Involves accountability to higher positions with responsibility.

2. Material and methods

Annually, the Public Employee Area of the Seville Provincial Council manages the training of the personnel belonging to said public institution. The main objective is to respond to the emerging training needs that the assigned personnel may present.

The intervention “Mindfulness: Cultivating conscious attention” is therefore designed as a response to the needs presented from various sources within the Continuous Training Department. It has responded to the needs for mindfulness since 2018 and until the end of 2021, during 14 implemented editions, 6 of them face-to-face (2018/2019).

The majority profile is personnel working with youth, elderly, and/or social inclusion collectives of the Seville Provincial Council and its agencies, personnel from municipalities, associations, and consortia of the province of Seville (Seville Provincial Council, 2019). The course has also had professionals from other fields such as members of local security forces, professionals in the psychological and legal fields, and maintenance personnel.

The training action “Mindfulness: Cultivating conscious attention” is a Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI), which takes the reference of three different mindfulness protocols for its design, in terms of content index, duration, and organization. Mainly, the protocol of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction MBSR by Kabat-Zinn (1982; 1990) is taken as a model for the order of the first six sessions, with certain modifications and the introduction of complementary materials. On the other hand, references are taken from the Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy MBCT (Cognitive Therapy based on Mindfulness for Depression) protocol to design content related to the knowledge and management of thoughts (Segal et al. 2002; 2006). Finally, from the Mindfulness Self-Compassion MSC program by Neff & Germer (2013; 2019), a specific module is incorporated where self-compassion has a relevant weight. The index of the training action is established as follows:

•Topic 1. What is mindfulness. Basic awareness.

•Topic 2. Mindfulness, attention, and brain neuroplasticity.

•Topic 3. What are thoughts and how to manage them. Elements of the mind.

•Topic 4. Stress as an evolutionary response. Respond instead of reacting.

•Topic 5. Emotion management from mindfulness.

•Topic 6. Non-violent communication and conflict management.

•Topic 7. Compassion and loving-kindness.

Different issues have been assessed from this intervention, but in the article, the results of the transfer questionnaire are described:

The transfer of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes acquired to the job position, as a response to whether the participating individuals have applied what they learned in the training action in their job positions.

Transfer analysis This questionnaire follows the FET model (validated in 2011). This model, and the questionnaire derived from it, has served as a basis for developing a specific questionnaire adapted to the context of the Diputación de Sevilla and the implemented training action. It aims to analyze knowledge transfer and the effectiveness of transferring mindfulness to the workplace. Therefore, the methodological perspective adopted in this work has an integrative and comprehensive approach to phenomena, falling within the type of non-experimental research. It is framed as non-experimental methodology, given that no situation or control group is generated, but rather the situations that develop after the implementation of the training intervention are observed (Hernández-Sampieri et al., 2010).

Transfer evaluation questionnaire The data extracted for our research are those collected in the knowledge transfer questionnaire to the workplace, demanded by the Diputación de Sevilla from participants in the 2019 training action editions. To analyze the effectiveness of the transfer of mindfulness knowledge to the workplace, a specific questionnaire has been developed, responding to the parameters established by the Diputación de Sevilla. One of the most notable aspects is that a maximum of 13 items is established when preparing the transfer evaluation questionnaire. This aspect has forced a thorough adaptation and analysis of which factors from the FET model with 42 items (Pineda-Herrero et al., 2020) needed to be emphasized and which could be left out of the analysis when preparing the questionnaire used. Thus, the questionnaire has finally focused on the following factors of the FET model, which have already been defined in the previous section:

•Environment possibilities for application.

•Motivation to transfer.

•Support for transfer.

•Internal locus of control.

Finally, the questionnaire consists of 13 items, as established by the Diputación de Sevilla. Items 1 to 12 have a Likert-type closed response scale from 1 to 5, where 1 corresponds to “Completely disagree” and 5 corresponds to “Completely agree”. Item 13 does not follow this type of response as it is an open-ended question. The questionnaire is configured as follows: Items 1 to 8 focus on analyzing to what extent the knowledge and competences acquired in the training action have been applied to the workplace and to what extent this has helped to improve the work performance of each participant. In this way, the extent to which MBI has fostered greater innovation, increased motivation or performance is analyzed. It should also be noted that items 7 and 8 have an inverse result, having been formulated in a negative sentence. Items 9 to 12 specifically focus on analyzing the perceived effectiveness of the mindfulness knowledge, procedures, and attitudes acquired and their applicability in the work environment. Finally, item 13, called observations, serves to collect the different experiences of the participating individuals regarding mindfulness, its applicability, and its contextualization in the work environment.

Population sample

The participants in the training program during the year 2019 consist of a total of 63 professionals from the Diputación de Sevilla (56 women and 7 men). These individuals attended the training program “Mindfulness: Cultivating Conscious Attention” after voluntarily requesting the course and being selected for it. The sample is composed of all participants in the three editions in which the transfer questionnaire was conducted.

Table 2. Number of participants by edition of the training program

|

Edition |

Dates |

Certified students |

Certified women |

Certified men |

|

2019_20190801 |

10/09/2019 al 01/10/2019 |

22 |

20 |

2 |

|

2019_20190802 |

03/10/2019 al 24/10/2019 |

21 |

18 |

3 |

|

2019_20190803 |

29/10/2019 al 19/11/2019 |

20 |

18 |

2 |

Source: own elaboration.

Age and gender

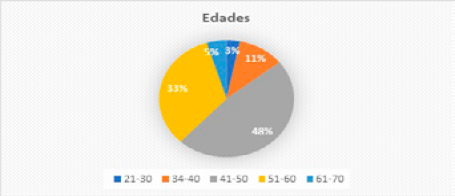

The information collected on the ages and genders of these individuals is as follows:

•21-30 years (3.17 %): 2 women.

•31-40 years (11.11 %): 6 women and 1 man.

•41-50 years (47.62 %): 27 women and 3 men.

•51-60 years (33.33 %): 18 women and 3 men.

•61-70 years (4.76 %): 3 women.

These data show that 80.95 %, the vast majority of participants, are in the age range of 41-60 years. On the other hand, 47.62 % are between 41-50 years old and 33.33 % are between 51-60 years old. The other age group is between 31-40 years, with a lower percentage (11.11 %). Finally, the extreme age groups of 21-30 years and 61-70 years show very small percentages of 3.17 % and 4.76 %, respectively. This information can be consulted in Figure 1. Percentage of participants by age.

Figure 1. Percentage of participants by age

Of the total participants in the three editions of the training program, 88 % were women and 12 % were men. This significant difference is often a constant factor to consider in mindfulness training. Both men and women are more represented in the age range of 41-60 years, perhaps indicating when people tend to train in mindfulness. This may be related to professional or personal processes that develop during these years of maturity.

Figure 2. Percentage of participants by gender

Based on the gender variable (56 women and 7 men), a higher number of women in all editions of the course were shown, with 88.88 %. This may be due to differential socialization, which contributes to women developing professions more focused on care and education due to gender stereotypes.

Educational level

The educational level of the people who participated in the training program is another variable that has been considered. The data are presented below:

Table 3. Educational level of participants

|

Educational level |

Mujeres |

Hombres |

|

Compulsory Secondary Education |

2 |

0 |

|

High School |

2 |

2 |

|

Professional Training |

15 |

1 |

|

Degree |

17 |

2 |

|

Bachelor degree |

16 |

2 |

|

Master’a degree |

5 |

0 |

|

PhD |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

57 |

7 |

As seen in Table 3. Level of education of participating individuals, in relation to the level of education, 66.67 % of the people who access the course have university studies, with the majority group being those with a diploma (30.16 %), followed by the group of people with a bachelor’s degree (28.57 %), and the percentage of people with third-grade university studies (Master’s degree) is only 7.94 %. Comparing this data based on the gender variable, 71 % of women have university studies, compared to 57 % of men.

Figure 3. Percentage of participants by educational level

3. Results

Next, we present the information obtained from the transfer questionnaire for the training course “Mindfulness: cultivating mindful attention”. The Provincial Government of Seville is responsible for selecting those training courses on which transfer to the job is evaluated, and to date, this course has not been evaluated in these terms again. The total number of people who have responded to the questionnaire is 48. We must remember that the total number of people who have completed and certified the three editions of the training course is 63 (56 women and 7 men). This means that 76.19 % of the people who participated in the training course have responded to the questionnaire. Regarding participation in the questionnaire by edition, 20 people would have participated in the questionnaire corresponding to Edition 1, 13 in Edition 2, and 15 people in Edition 3. The information collected in each of the items is described below:

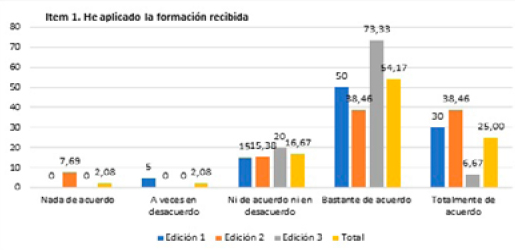

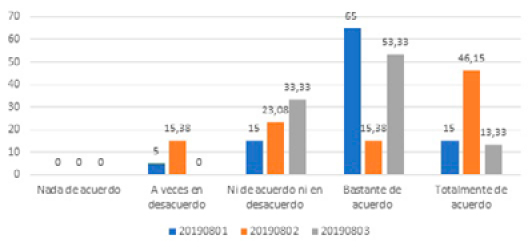

Item 1: I have applied the training received

The results obtained regarding whether “I have applied the training received” show 79.17 % in the sum of the values of “Quite agree” (54.17 %) and “Completely agree” (25 %). Therefore, it can be affirmed, based on the data obtained, that the application of the training received has been carried out in the vast majority of cases. In fact, negative values, “Not at all agree” and “Sometimes disagree”, only account for 4.16 % of the total. Finally, it should be noted that 16.67 % of the people who responded to the questionnaire maintain a neutral assessment in this regard. The data can be consulted in the following figure.

Figure 4. Results of responses to Item 1

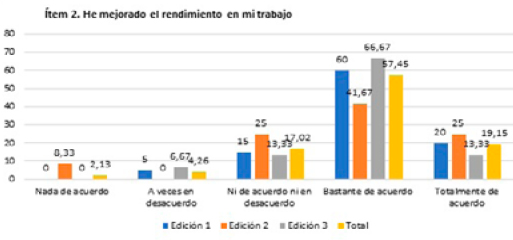

Item 2. I have improved my job performance

The data collected for this item, regarding the statement “I have improved my job performance,” is also very positive. At least 76.6 % of the respondents believe that they have improved their job performance, with 57.45 % indicating they are “Quite in agreement” and 19.15 % stating they are “Completely in agreement.” In contrast, only 6.38 % believe that they have not improved, with 2.13 % indicating they are “Not at all in agreement” and 4.26 % indicating they are “Sometimes in disagreement.” Lastly, it should be noted that 17.02 % are “Neither in agreement nor in disagreement.”

Figure 5. Results of responses to Item 2

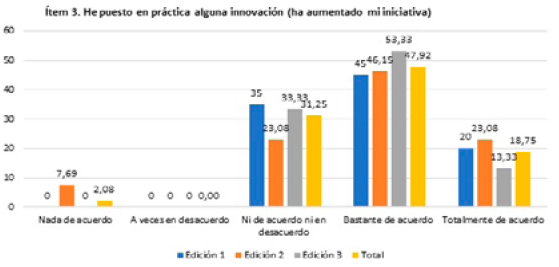

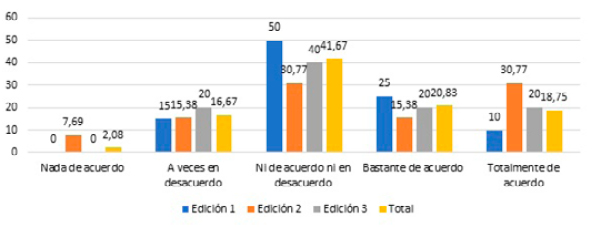

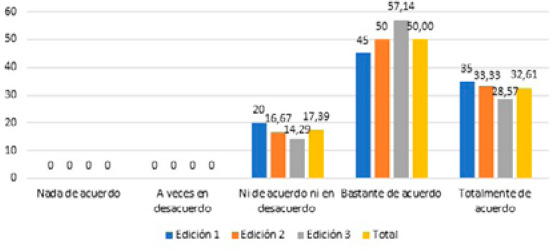

Item 3. I have implemented some innovation (my initiative has increased)

Regarding Item 3, which questions whether “I have implemented some innovation (my initiative has increased),” 66.67 % responded affirmatively, with 47.92 % of the respondents being “Quite in agreement” with the statement and 18.75 % being “Completely in agreement.” Negative scores are also much lower than the previous ones, as only 2.08 % (1 person out of the 3 editions) indicated they were “Not at all in agreement.” The percentage of people who indicate they are in an intermediate point “Neither in agreement nor in disagreement” is 31.25 %.

Figure 6. Results of responses to Item 3

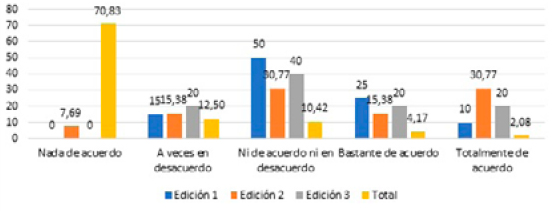

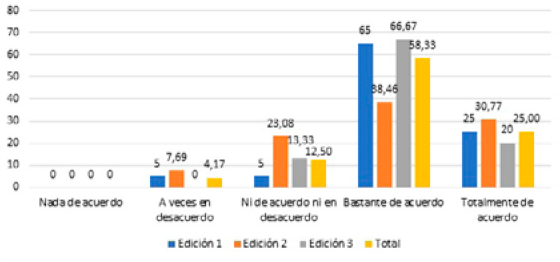

Item 4. My level of motivation at work has improved

Item 4 questions the level of agreement with the statement “My level of motivation at work has improved.” In this sense, 80 % of the people who participated in Edition 1 are “Quite in agreement” (65 %) or “Completely in agreement” (15 %) with this statement. Regarding Edition 2, the data indicates that 61.53 % are in agreement or completely in agreement with the statement, and for Edition 3, 66.66 % of the respondents to the questionnaire express their agreement on this matter.

In total, 70.83 % of the participants stated they were “Quite in agreement” (47.92 %) or “Completely in agreement” (22.92 %). Only 6.25 % of the total participants indicated they were “Sometimes in disagreement,” and 22.92 % indicated they were “Neither in agreement nor in disagreement.” In conclusion, the results indicate that going through the course has significantly increased motivation towards the work being done. The complete summary of data can be seen in both the following table and the figure.

Figure 7. Results of responses to Item 4

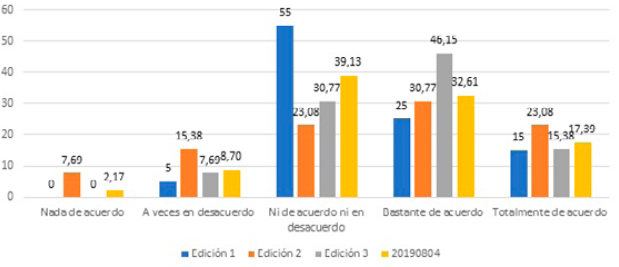

Item 5. The work environment facilitates the application of the training received

The results obtained regarding questioning the attendees whether “the work environment facilitates the application of the training received” are not as definitive and clear as in previous items. The majority of the respondents, with 41.67 %, indicate that they are “neither agree nor disagree” with the statement. 39.58 % of the surveyed individuals agree with the statement. Specifically, 20.83 % of them state that they are “Quite agree” and 18.75 % are “Completely agree”. On the other hand, 18.75 % disagree with the statement, with 2.08 % indicating that they are “Not at all agree” and 16.67 % are “Sometimes disagree”.

Overall, everything seems to indicate that the majority of the respondents think that the environment neither facilitates nor hinders the application of the knowledge acquired after participating in the intervention. However, the sum of the positive results is higher than the negative ones.

Figure 8. Results of responses to Item 5

Item 6. I have the necessary resources to apply the knowledge acquired in the workplace

In item 6, participants were asked whether they had “the necessary resources to apply the knowledge acquired in the workplace.” In this regard, 50 % of respondents answered positively, as 32.61 % strongly agreed and 17.39 % completely agreed. 10.87 % of respondents indicated disagreement, with 2.17 % indicating strong disagreement and 8.7 % indicating occasional disagreement. 39.13 % of responses did not lean towards either extreme and indicated neither agreement nor disagreement.

Figure 9. Results of responses to Item 6

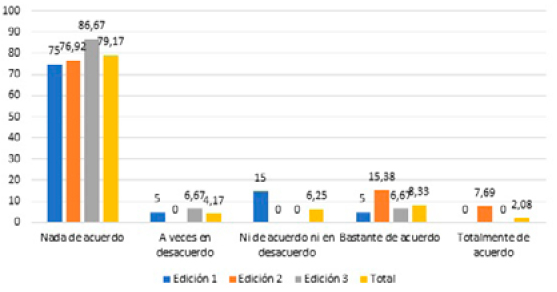

Item 7. Currently, I do not apply the knowledge learned because I am not working or I have changed positions

Item 7 is phrased in the negative, so the meaning of the responses must be reversed. In response to the statement “currently, I do not apply the knowledge learned because I am not working or I have changed positions,” the responses are very significant. 79.17 % of respondents answered “strongly disagree,” and 4.17 % of respondents indicated occasional disagreement. This suggests that 83.34 % of people continue to work in their same positions and apply the knowledge learned. Only 10.41 % agreed with the statement, with 8.33 % strongly agreeing and 2.08 % completely agreeing. In this item, intermediate responses are lower compared to other items, as only 6.25 % of respondents indicated neither agreement nor disagreement.

Figure 10. Results of responses to Item 7

Item 8. I do not apply what I have learned because it is not within the competences of my job position

Item 8, like the previous item, is also formulated in a negative way. In this sense, with respect to the phrase “I do not apply what I have learned because it is not within the competences of my job position,” 6.25 % of the surveyed individuals agree with the statement (4.17 % “somewhat agree” and 2.08 % “totally agree”). The majority of the responses, that is, 83.33 %, are contrary to this phrase. Thus, 70.83 % of the people comment that they “strongly disagree” and 12.5 % are “sometimes in disagreement”. Like item 7, the intermediate responses are also low, accounting for only 10.42 %. Most of the participants who have responded understand that the acquired knowledge is perfectly applicable to their job position and, in fact, is part of the competencies required for that position.

Figure 11. Results of responses to Item 8

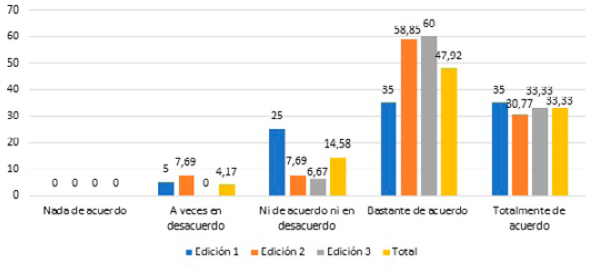

Item 9. The knowledge about Mindfulness (mindfulness, stopping, focusing, single-tasking, nonviolent communication, compassion, etc.) has allowed an improvement or empowerment in your professional life

Item 9 is the first in the questionnaire that focuses specifically on the topic of training action. When asked if the knowledge acquired about mindfulness has allowed an improvement or empowerment in the professional field, 81.25 % of the respondents agreed. Specifically, 47.92 % indicated they “somewhat agree” and 33.33 % indicated they “totally agree”. Only 4.17 % indicated they “sometimes disagree” with the statement, which would not be a strongly negative response in any case. 14.58 % of the responses maintain an intermediate profile by indicating they are “neither agree nor disagree”.

Figure 12. Results from Item 9 responses

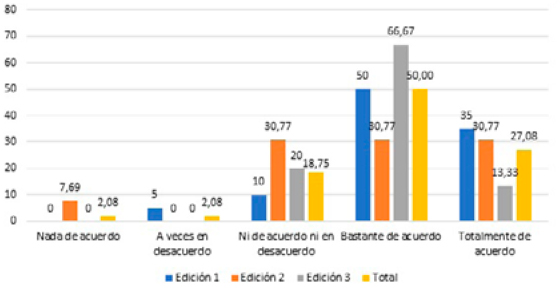

Item 10. Knowing how stress works and its power to generate automatic reactions, as well as the ability we have worked on to stop and bring our attention to our breathing, refocusing on the situation that stresses us without judgment and accepting the reality around us, has improved my daily functioning in my workplace

Regarding the statement in Item 10, which focuses on questioning the ability of mindfulness to “improve daily functioning in the workplace,” 77.08 % of respondents agree. Specifically, 50 % of people strongly agree with the statement and 27.08 % indicate that they totally agree. On the other hand, only 4.17 % of people disagree with the statement (2.08 % for both the “Not at all agree” and “Sometimes disagree” ratings). 18.75 % of responses are neither in agreement nor disagreement with the statement.

Figure 13. Results from Item 10 responses

Item 11. After taking the course, I can talk about an increase in self-awareness, improvement in attention, ability to concentrate, active listening, etc. in my work position

Item 11 asks if “After taking the course, I can talk about an increase in self-awareness, improvement in attention, ability to concentrate, active listening, etc. in my work position.” The positive results to this statement are very high, as 83.33 % of respondents answered in such a way, where 58.33 % strongly agree and 25 % totally agree. 4.17 % of people indicated they are sometimes in agreement or not in agreement, and no one indicated they are not at all in agreement. 12.5 % of responses did not lean towards either end, indicating they are neither in agreement nor in disagreement.

Figure 14. Results from Item 11 responses

Item 12. We have worked on understanding and accepting emotions, managing their influence on decision-making (response vs reaction) and in our interpersonal relationships, and I have noticed the benefits of the knowledge acquired in my work environment.

Item 12 considers the benefit of knowledge acquired in the work environment from understanding and accepting emotions, managing them in decision-making, and how they influence interpersonal relationships. Here, 82.61 % of people responded positively, where 50 % were quite in agreement and 32.62 % were completely in agreement. The remaining 17.39 % of responses did not have a clear determination, answering neither agree nor disagree. No results were obtained for responses sometimes in disagreement or not in agreement at all.

Figure 15. Results of responses to Item 12

Item 13. Observations (Add any comments you consider relevant regarding the applicability of what you have learned to your job)

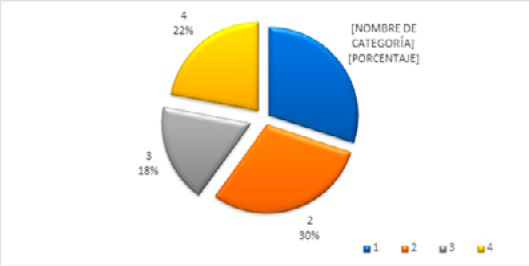

Item 13, observations, allowed each participant to add comments regarding the applicability of what they learned to their job. The 22 results shown are global for the three editions. They have been grouped into four categories that refer to the usefulness of mindfulness in personal and work growth, as well as the importance of its application in work environments. Finally, it should be noted that there is a need to continue with deeper or more extended mindfulness training.

C1_Mindfulness is useful for my personal growth. 7 responses

C2_Mindfulness is useful for my work growth. 7 responses.

C3_Mindfulness should be applied in the work environment. 3 responses

C4_Mindfulness training should be expanded to another edition, longer duration, or more depth. 5 responses

Figure 16. Results of responses to Item 12

4. Discussion

The information obtained from the questionnaire provides enough data to affirm that both the set objectives and the hypotheses proposed about the transfer of knowledge related to mindfulness to the workplace have been fulfilled. Motivation, involvement, active listening, self-awareness, and interpersonal relationships have been improved, as well as the work environment. In this section, the correspondence between objectives, hypotheses, and the items involved in their achievement is presented in a graphic and descriptive way.

Regarding the first objective and its correspondence with the first hypothesis, it has been fulfilled, as shown by the obtained average data, by achieving 63.75 % of positive results. The items that are taken to make such an affirmation are:

•Item 1 I have applied the training received.

•Item 5. The work environment facilitates the application of the training received.

•Item 6. I have the necessary resources to apply the knowledge acquired in the workplace.

•Item 7. Currently, I do not apply the knowledge learned because I am not working or have changed positions.

•Item 8. I do not apply what I have learned because it is not within the scope of my job.

Table 4. Relationship between OE1-H1 and items

|

OBJETIVE |

HYPOTHESIS |

ITEMS |

RESULTS POSITIVE |

|

OE1. Analyze the level of transfer and applicability of knowledge to the job after the training action. |

H1. Participation in the training action “Mindfulness: Cultivating mindful attention” will enhance among participants a set of knowledge, procedures, and attitudes applicable to their jobs. |

1 |

79,17 % |

|

5 |

39.58 % |

||

|

6 |

50 % |

||

|

7 |

79.17 % |

||

|

8 |

70.83 % |

||

|

Total: 63.75 % |

|||

As can be seen, most of the items score above 70 %. However, in item 5 (39.58 %) and item 6 (50 %), participants’ perception is not as positive. From this, it can be deduced that participants feel that they do not have the necessary means and resources to practice mindfulness at their workplaces. Nevertheless, despite this, the overall results indicate that participants in the training action “Mindfulness: Cultivating mindful attention” have applied the acquired knowledge to their jobs. This implies that although these individuals do not have resources at their workplaces, they consider themselves capable of applying the acquired mindfulness knowledge to their jobs, showing clear transfer of knowledge from the training action to their work life (Pineda et al., 2020).

Regarding the second objective and hypothesis, the information derived from the results confirms with 74.42 % that individuals who have participated in the training action “Mindfulness: Cultivating mindful attention” improve their job performance. The items analyzed are:

•Item 2. I have improved my job performance.

•Item 3. I have put some innovation into practice (my initiative has increased).

•Item 4. My level of motivation at work has improve.

Table 5.Relationship between OE2-H2 and items

|

OBJETIVE |

HYPHOTESIS |

ITEMS |

RESULTS POSITIVE |

|

O.E.2. To determine if the training carried out has had a direct impact on the improvement of job performance of the participants. |

H2. Participants in the training program “Mindfulness: Cultivating mindful attention” will improve their job performance in terms of performance, initiative, and motivation. |

2 |

76.60 % |

|

3 |

66.67 % |

||

|

4 |

80 % |

||

|

Total: 74.42 % |

|||

The data indicates that those who participated in the training program believe they have improved their job performance, as well as increased innovation, initiative, and motivation in their work. It should be noted that these three attitudes involve introducing innovations and initiatives in the development of work, which often improve organizational processes. On the other hand, increased motivation in the actions we perform confers empowerment at the work level, making us feel like an active part of the organization’s productive process, generating a process of engagement, that is, greater emotional connection which results in a greater commitment to the activities performed (Ballesteros, 2018).

After this, it can be mentioned that, at the corporate level, continuous mindfulness training promotes internal factors in the improvement and gain of effectiveness that a person can develop in their work position, leading to higher productivity, innovation, initiative, and motivation.

Finally, the data obtained in items 9, 10, 11, and 12 are described, from whose results it can be deduced that the third objective and the third hypothesis are fulfilled. The items are presented as a reminder:

•Item 9. Knowledge about Mindfulness (mindful attention, stopping, focusing, single-task attention, nonviolent communication, compassion, etc.) has enabled an improvement or empowerment in your professional life.

•Item 10. Knowing the functioning of stress and its power to generate automatic reactions, as well as the capacity that we have worked on to stop and bring our attention to breathing, focusing again on the situation that stresses us without judgments and accepting the reality around us, I have improved my daily functioning in my workplace.

•Item 11. After completing the course, I can speak of an increase in self-awareness, improvement in attention, ability to concentrate, active listening, etc. in my work position.

•Item 12. We have worked on understanding and accepting emotions, managing their influence on decision-making (response VS reaction) and on our interpersonal relationships, and I have noticed the benefits of the acquired knowledge in my work environment.

Table 6. Relación entre OE3-H3 con los ítems

|

OBJETIVE |

HYPHOTESIS |

ITEMS |

RESULTS POSITIVE |

|

OE3. To assess the perceived effectiveness after participation of mindfulness for participants in the training intervention. |

H3. Participants in the “Mindfulness: Cultivating mindful attention” training intervention will perceive the effectiveness of the knowledge acquired about mindfulness in their job positions. |

9 |

81.25 % |

|

10 |

77.08 % |

||

|

11 |

83.33 % |

||

|

12 |

82.60 % |

||

|

Total: 74.42 % |

|||

People who received continuous training in mindfulness perceive the effectiveness of the knowledge acquired in aspects such as mindful attention, nonviolent communication, or compassion in their job positions. Regarding stress and acquired mindfulness abilities, participants consider that it has improved the daily functioning of their workplaces. Likewise, the data confirms that those who have received MBI appreciate an increase and improvement in self-awareness, concentration, active listening, and the ability to respond rather than react to emotions, among others. All these knowledge, procedures, and attitudes allow us to flow in workspaces. Likewise, interpersonal relationships are also optimized when we converge with active listening, non-judgment, and acceptance (Rosenberg, 2016). All of this makes such participants perceive the acquired knowledge as beneficial both in their work and personal environments. These mindfulness abilities influence their improvement or empowerment in their job positions (Simón, 2011).

Finally, item 13 collects 22 observations that can be grouped into four general statements:

1.“Mindfulness is useful in personal growth.”

2.“Mindfulness is useful in job growth.”

3.“Mindfulness should be applied in the workplace.”

4.“Mindfulness training should be expanded.”

These results confirm that those who have participated in mindfulness training perceive growth at both personal and job levels, allowing them to develop a series of attitudes that promote more optimal interpretations and actions regarding life’s demands.

After the analysis carried out, it is possible to conclude that continuous training in mindfulness has generated significant changes in the workers of the Diputación de Sevilla. Participation in the “Mindfulness: Cultivating mindful attention” training intervention has improved, among other aspects, motivation, innovation, concentration, and performance of the participants in their respective job positions. Likewise, it has contributed positively to interpersonal relationships in matters such as active listening and compassion. Their training has also enhanced their capacity for accepting reality and resilience in the face of some work aspects that could result in rejection. It has also consolidated the affirmation that mindfulness reduces stress since actions such as learning to stop, focusing attention on breathing, developing non-judgmental mental processes, or establishing single-task actions, instead of reacting, favor the issuance of more appropriate responses to the demands that the environment presents on a daily basis. It is, therefore, a better way to flow with the environment through the development of optimal health capacities that generate a greater sense of well-being and empowerment in the actions that are carried out. And all of this also influences other people and the environment where we work, favoring the creation of healthier and more suitable environments for the development of job functions.

However, despite all the benefits and positive impacts of MBI, there are organizational issues that should be modified or integrated into the continuing education of the Diputación de Sevilla. A series of actions are proposed in this regard that are considered necessary to consolidate the knowledge acquired in mindfulness, as well as to deepen it.

At the organizational level, it would be necessary to facilitate the training and practice of mindfulness, based on two key aspects:

•Training: It would be necessary to expand mindfulness training at different levels in order to deepen practical and theoretical knowledge of mindfulness.

•Times and spaces for practices: Promote mindfulness practice groups in different workplaces in case the people who work there request it.

On the other hand, attitudes such as active listening, non-judgment, or acceptance, among others, will improve attention to users at a global level. Increased motivation, performance, and productivity will generate high results at the organizational level and progress and empowerment in terms of professional and personal development of the entire staff. All of this will contribute to better health and a general sense of well-being, promoting a decrease in absenteeism, thanks to the effective reduction of stress or other issues such as anxiety that mindfulness practice has demonstrated to reduce (Altman, 2019; Rosenberg; Sainz Martínez, 2017).

5. Conclusions

When Mindfulness is incorporated into the corporate culture, changes occur that favor a better communicative climate, the creation of more fluid interpersonal relationships, resilience in the face of unexpected events, more creative and innovative responses, the development of leadership capacity and decision-making, etc., (Glomb et al., 2011; Steyn, 2013).

Many outstanding companies have introduced meditation and other mindfulness techniques as a highly useful tool for the development of their personnel. Several studies, such as those conducted from 2016 to 2020 by the Adecco Group Institute and Fidelity Investments, showed that of the 102 companies certified as Top Employers, 65 had continuous training initiatives in mindfulness, silent spaces for meditation, or conscious eating practices. In addition, 80 % of the organizations surveyed planned to introduce mindfulness training in the coming years. All the studies carried out concluded that mindfulness training in companies provides a series of benefits in the workplace such as: improving the well-being and resilience of staff, increasing productivity, improving leadership skills and interpersonal relationships, creativity and innovation, development of decision-making skills, etc. (Adecco 2016, 2018, 2020).

When this type of intervention is applied, one of the most relevant issues is to analyze the transferability of the training action to the workplace. Baldwin and Ford (1988) define this issue as the level to which each participant applies the knowledge, skills, and attitudes acquired in their work context. That is, transfer occurs when the acquired knowledge is applied to the work context, remaining for a period of time. Specific instruments are required to measure transfer. In this sense, the contributions of Pineda, Quesada and Moreno (2010); Pineda, Úcar, Moreno y Belvis (2011); Porto, García y Navarro (2013) are relevant.

There are many reasons why mindfulness gains strength in the business context, but it becomes evident that the most necessary for the proper functioning of an organization is the search for the health and well-being of its workers. For this, it is essential to know that when working conditions are bad, deficient or adverse, they have a negative impact on the safety, health, and well-being of workers, becoming a source of risk that must be managed (González-Ortiz et al., 2017; Pineda et al., 2020; López-García, 2021).

Bibliographic references

. (2018). Mindfulness. https://adecco.cl/mindfulness/

. (2020). Beneficios del mindfulness en el trabajo https://www.adeccoinstitute.es/articulos/beneficios-del-mindfulness-en-el-lugar-de-trabajo/

(2016). Practicar el mindfulness aumenta un 20 % nuestra productividad, https://www.adeccorientaempleo.com/mindfulness-aumentar-productividad/

(2019). 50 técnicas de Mindfulness para la ansiedad, la depresión, el estrés y el dolor. Libros Sirio.

(2018). El índice de engagement en redes sociales, una medición emergente en la Comunicación académica y organizacional. Revista Razón y Palabra, 102, 96-124. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6787048&orden=0&info=link

, y (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15(5),593-600. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2008.0495

(2004). El porqué de la responsabilidad social corporativa. Boletín ICE Económico, 2813, 45-58. http://www.revistasice.com/index.php/BICE/article/view/3598/3598

Diputación de Sevilla (2019). Manual de Formación Plan Agrupado de Formación Continua. Diputación de Sevilla. https://bit.ly/2X3w3Xh

, , , y (2010). Minding one’s emotions: Mindfulness training alters the neural expression ofsadness. Emotion, 10, 25–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0017151

, y (2018). Manual Práctico de responsabilidad social corporativa. Gestión, diagnóstico e impacto en la empresa. Editorial Pirámide. https://www.tagusbooks.com/leer?isbn=9788436840063&li=1

y (2018). ¿Qué sabemos del Mindfulness? Kairós.

, , , & (2021). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on psychotherapy processes: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(3), 783-798. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2676

(2011). El poder del mindfulness: libérate de los pensamientos y las emociones autodestructivas. Paidós.

y (2019). Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC). En I. Itvzan (Ed.) The handbook of mindfulness-based programs: Every established intervention, from medicine to education (357-367). Routledge.

, , and (2011). Mindfulness at Work. En Joshi, A., Liao, H. y Martocchio, J.J. (Ed.), Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management. 30 (pp. 115-157). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0742-7301(2011)0000030005

, , & (2017). Evaluación de la eficacia de la formación en la administración pública: la transferencia al puesto de trabajo. INAP.

(2020). Being peace. Parallax Press.

, , y (2014). Metodología de la investigación (6a. ed.). McGraw-Hill.

, , (2016), Intervenciones psicológicas basadas en mindfulness y sus beneficios: estado actual de la cuestión. Clínica y Salud, 27 (3), 115-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clysa.2016.09.002

(2015). On the contemporary applications of mindfulness: Some implications for education. Journal of philosophy of education, 49(2), 170-186. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12135

(1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General hospital psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3

(1990). Vivir con plenitud las crisis. Editorial Kairós

(2018). Mindfulness in the workplace. Strategic HR Review, 17(2), 76-80. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-11-2017-0077

(2021). Eficacia de un programa Mindfulness (Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) en psicoterapeutas: una propuesta 2.0. Norte de Salud Mental, 17(65), 11-24. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8047260

, , , , & (2021). The costs of mindfulness at work: The moderating role of mindfulness in surface acting, self-control depletion, and performance outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(12). https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000863

(2006). Anatomía del miedo. Un tratado sobre la valentía. Anagrama.

(2008). Responsabilidad Social Corporativa. Teoría y Práctica. ESIC Editorial.

y (2013), A Pilot Study and Randomized Controlled Trial of the Mindful Self-Compassion Program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 28-44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21923

, , , , & (2011). Evaluation of training effectiveness in the Spanish health sector. Journal of Workplace Learning. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665621111141911

, , & (2014). ¿Cómo saber si la formación genera resultados? El modelo FET de evaluación de la transferencia. Capital Humano, 292, 74-80.

, , & (2010). The ETF, a new tool for Evaluating Training Transfer in Spain. In 11th International Conference on Human Resource Development: Human Resource Development in the Era of Global Mobility. https://grupsderecerca.uab.cat/efi/en/content/etf-new-tool-evaluating-training-transfer-spain

, , & (2011). Evaluating the efficacy of e-learning in Spain: a diagnosis of learning transfer factors affecting e-learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 2199-2203. http://hdl.handle.net/11162/79202

, , (2020). Factores para la Evaluación indirecta de la Transferencia – FET. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

, y (2013). Evaluación de la transferencia de la formación continua mediante el modelo ETF de factores. Revista Iberoamericana de educación, 61 (1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie6111273

, , & (2011). Evaluating the efficiency of leadership training programmes in Spain. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 2194-2198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.427

(2016). Comunicación No Violenta. Un lenguaje de vida. 3ªedición renovada y ampliada. Editorial Acanto.

(2017). Mindfulness en la empresa: el liderazgo mindful como transformación personal, empresarial y global. Zenith.

, , y (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. Guilford.

, y (2006). Terapia cognitiva de la depresión basada en la atención plena: Un nuevo abordaje para la prevención de recaídas. Desclée De Brouwer.

(2019). Educación para una atención eficiente. La naturaleza de la atención. Asociación filosófica Vedanta Advaíta Sesha.

y (2014). Arte y ciencia de mindfulness. Desclée de Brouwer.

(2011). Aprender a practicar Mindfulness. Sello Editorial.

(2013). Professional and organisational socialisation during leadership succession of a school principal: a narrative inquiry using visual ethnography SA. Journal of Education, 33 (2), 1-17. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0256-01002013000200010&lng=en&nrm=is

(2018). Building the case for Mindfulness in the Workplace. Mindfulness Initiative.

Tomás-Folch, M. y Durán-Bellonch, M. (2017). Comprendiendo los factores que afectan la transferencia de la formación permanente del profesorado. Propuestas de mejora. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 20(1), 145-157. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/reifop.20.1.240591

, , , , , & (2013). One-pot synthesis of magnetic hybrid materials based on ovoid-like carboxymethyl-cellulose/cetyltrimethylammonium-bromide templates. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 141(2-3), 735-743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2013.06.001

, & (2019). Advancing environmental productivity: Organizational mindfulness and strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(3), 447-456. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2220

(2019). Atención plena. Mindfulness basado en la tradición budista: Teoría y práctica (Sabiduría perenne). Editorial Kairós.