E-instantáneas culturales como recurso digital: análisis de su influencia en la competencia digital

Cultural e-snapshots as a digital resource: analysis of their influence on digital competence

Ernesto Colomo Magaña

Universidad de Málaga

Andrea Cívico Ariza

Universidad Internacional de Valencia

RESUMEN

Los avances tecnológicos permiten crear diferentes tipos de recurso educativos. Las instantáneas culturales, vinculadas a narraciones que conjugan el cine, la música y la literatura, son ahora desarrolladas a través de vídeos, blogs o podcast, denominándose e-instantáneas. La creación de estos recursos digitales influye en el desarrollo de la competencia digital. Debido a ello, el objetivo de este estudio es conocer la influencia que la elaboración de e-instantáneas culturales tiene en el nivel de competencia digital de futuros docentes. Se aplicó un diseño cuantitativo de panel longitudinal (pre-test y post-test), con un enfoque descriptivo e inferencial. La muestra la componen 113 futuros docentes de primaria de la Universidad de Málaga (España) en el curso 2021/2022. Se utilizó como instrumento el Cuestionario de Competencia Digital para Futuros Docentes. Los resultados indican una percepción notable del nivel de competencia digital tras crear las e-instantáneas, mejorando de forma significativa respecto al momento anterior a su desarrollo. En cuanto a la variable sexo, existen diferencias significativas en favor de los hombres. Como conclusión, la creación de e-instantáneas culturales supone una alternativa creativa para el diseño de recursos educativos que favorece la mejora de la competencia digital.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Competencia digital; innovación pedagógica; docentes en formación; tecnología educativa; instantánea cultural.

ABSTRACT

Technological advances make the creation of different types of educational resources possible. Cultural snapshots, linked to narratives that combine cinema, music, and literature, are now developed through videos, blogs, or podcasts, and are called e-snapshots. The creation of these digital resources influences the development of digital competence. Due to this, the objective of this study is to determine the influence that the creation of cultural e-snapshots has on the level of digital competence of pre-service teachers.

A quantitative longitudinal panel design was applied (pre-test and post-test), with a descriptive and inferential approach. The sample is made up of 113 pre-service primary teachers from the University of Malaga (Spain) during the 2021/2022 academic year. The Digital Competence Questionnaire for Pre-service Teachers was used as an instrument. The results indicate a notable perception of digital competence levels after creating the e-snapshots, improving significantly with respect to the moment prior to their development. Regarding the gender variable, there are significant differences in favour of men. In conclusion, the creation of cultural e-snapshots is a creative alternative for the design of educational resources that favours the improvement of digital competence.

KEYWORDS

Digital competence; teaching method innovations; teachers in training; educational technology; cultural snapshots.

1. Introduction

The concept of culture is a multifaceted reality that has evolved and transformed throughout history (Seidmann, 2022). Among the different definitions, the focus in this case is placed on the content or information that is socially transmitted, considering everything that a person can acquire and transmit through a learning process that gives meaning to the sociocultural reality that surrounds us. Therefore, culture would be a learned behaviour (Pupo, 2014), where the so-called cultural elements would constitute the channel through which people become familiar with and learn a culture as well as some of the values that prevail and give meaning to it (Colomo, 2014). For the acquisition of all these aspects, education becomes the fundamental instrument and vehicle of cultural transmission (Jiménez et al., 2020; López et al., 2020). From the moment they are born, people are exposed to a determined cultural manifestation and to continuous teaching and learning processes that shape, condition, and define them, in order to make them social members of the reference group to which they belong. To this end, the process of continuous interaction between the subject and other members of the community is key (Jagielska-Burduk & Stec, 2019; Luna et al., 2019), where each human being develops their personality through a process of introspection and personal (re)construction. In connection with this process, it should be emphasized that people are social beings who learn in contact with others. Based on the latest proposals around Bandura’s Social Cognitive Learning Theory (2011), the observation of the behaviours of other people similar to us can be fundamental for the development of new, self-regulated learning (Barbosa & García, 2021; Muquis, 2022). For this reason, the emotional component is particularly important (Bisquerra & García, 2018; Rodríguez & Cantero, 2020), since preferences and tastes influence knowledge acquisition, and it is even more relevant in the field of cultural aspects.

Building on the above, the use of cultural snapshots (Esteban, 2016) and their digital version, cultural e-snapshots, is proposed as a particularly interesting resource for developing educational processes. Cultural snapshots are the result of selecting and combining various cultural resources that belong to three fine arts categories such as cinema, music, and literature, which allow for a clearer and simpler representation and exemplification of abstract contents for learning, thereby favouring a higher level of understanding. In this way, students reflect on a reality or issue that may be their own or someone else’s and that goes beyond what they are simply reading, watching, or listening to. It is worth highlighting the connection between this resource and the students’ deepest emotions since they put themselves in the protagonist’s place and translate the stories to the most intimate level, thereby producing an internalisation of culture (Bisquerra & García, 2018).

Despite the interest sparked by the elements involved in snapshots, today’s information society has incorporated new elements of cultural consumption linked to different technological devices (Colomo et al., 2022a; Romero et al., 2021). Moreover, the way people communicate and interact has changed (Cabero et al., 2022), making it necessary to use educational tools with new, more motivating formats that are tailored to the interests of the participants (Colomo et al., 2022b). This aspect leads us to discuss not only cultural snapshots, but also cultural e-snapshots to better align with our current reality. However, cultural snapshots revolve around storytelling, which must also be present in order to construct e-snapshots. In this way, resources such as podcasts, blogs, or social media posts, and short films, reels, or videos on TikTok can compose new cultural e-snapshots as long as the narrative element is present and facilitates the understanding of the content that is meant to be addressed.

Since there are no precedents for e-snapshots in the scientific field, it is worth highlighting the benefits of the digital resources that will form them. Videos constitute an audio-visual combination that allows stories and content to be conveyed, their greatest strength being the transmission of emotions (Ríos & Romero, 2022). Additionally, the autonomy involved in their viewing makes them a self-study strategy for learning (Roque, 2020). As for blogs, they stand out for their ease of use and the wide range of writing possibilities that combine texts with images, sounds, and links (Pedrero & Morón, 2016). Blogs favour autonomous learning (Aguaded & López-Meneses, 2009), making students the protagonists of the process, with their responsibility for the transferred information being motivational. The communicative potential of blogs must be added to this if there are interactions between the authors and visitors or readers of a given blog (Marín et al., 2020). With regard to podcasts, they stand out for their ability to share content (García & Aparisi, 2020) without playback limits (García-Aretio, 2022), their narrative structure being close to the radio world, which makes them attractive for complementing other existing resources (González et al., 2022).

While implementing e-snapshots in the classroom favours the understanding of contents, their creation also influences the development of students’ digital competence. In this sense, we are faced with a key competence within an increasingly technological reality, and its development among education professionals is necessary for successful training processes. (Cabero et al., 2020a; Gabarda et al., 2022; López-Belmonte et al., 2020; Marín Suelves et al., 2019).

Considering all of the above, this study aims to determine the influence of the creation of cultural e-snapshots on the level of digital competence of pre-service teachers. Specifically, perceptions before and after the creation of e-snapshots will be analysed, and the existence of significative differences in digital competence levels according to gender and the time of analysis will be examined.

Related studies

With respect to other works on digital competence, which is the focus of this study, Aguilar et al.’s (2022) study, with 84 new students in the Early Childhood and Primary Education degree programs at the University of Malaga, found notable perceptions regarding the students’ digital competence levels. Male participants obtained better results than females in their study, constituting a significant difference. A study carried out by Cañete et al. (2022) follows the same lines with regard to differences according to gender, although the 330 pre-service teachers’ levels of digital competence were quite basic. However, there are also studies where no differences according to gender were found in self-perceived levels of digital competence, such as one by Usart et al. (2021). Since cultural e-snapshots are a completely new concept, in order to consider how they influence the development of digital competence, the related studies will use the elements that make up e-snapshots as a reference-namely, the creation and publication of videos instead of films, blogs as an alternative to literature, and podcasts as an option for music.

In relation to videos, their inclusion favours the improvement of digital skills, thanks to the use of mobile phones as an educational element and to free editing programmes as well as dissemination on social media. Cassany and Shafirova (2021) reflected this after analysing 203 videos created by students and distributing a survey to 1,561 teachers, revealing that the creation of videos influences the learning of curricular content and the development of digital competence and creativity. Moreno et al. (2020), for their part, found that the creation of videos by 50 pre-service secondary teachers favoured better digital competence, although the educational quality of the videos could be improved, with the inclusion of pedagogical aspects in the video creation process being key.

As for blogs, a study carried out by Álvarez (2018) proposes the use of blogs as an educational resource, making students more proactive in the acquisition of history class contents and also improving their level of digital competence. Marín (2016) had similar results where pre-service primary teachers indicated the usefulness of blogs for curricular development and the improvement of digital competence.

Podcasts, for their part, help in the acquisition of knowledge, increasing student motivation and improving their digital competence when they create podcasts, as seen in the study carried out by García-Hernández et al. (2022) in the subject of geography. Along the same lines, Ortega’s (2019) study highlights that podcasts are a very interesting didactic resource in second language acquisition, as they reduce anxiety and increase self-esteem as well as improve students’ digital competence throughout the process.

2. Materials and methods

Design

From an ex post facto and pre-experimental approach, a quantitative study was conducted with a longitudinal panel design with pre-test and post-test measures. The information was obtained by carrying out a test on the self-perceived level of digital competence in pre-service teachers, applied before the creation of cultural e-snapshots and after their development (pre-test and post-test). After collecting the data, descriptive and inferential analyses were carried out on the sample as a whole, including gender as a variable to be considered.

Sample

Regarding the participants, a convenience sample (non-probability) was carried out among students in the “Theory of Education” course of the Primary Education degree at the University of Malaga during the 2021/2022 academic year. The final sample consisted of 113 students, 26 of whom were male (23.01 %) and 87 female (76.99 %), with an average age of 18.81±1.082.

Instrument

To examine pre-service primary teachers’ perceptions of their level of digital competence, the Digital Competence Questionnaire for Pre-service Teachers (DCQPT) (Cabero et al., 2020b) was applied. This questionnaire was constructed based on the ISTE digital competence development framework (Crompton, 2017) and the Dig-Comp framework (Carretero et al., 2017). The DCQPT was organised into 5 dimensions and 20 items using an 11-point Likert scale (0-10 inclusive) to make the evaluations. In this sense, the lower the score, the lower the level of digital competence in pre-service teachers and vice versa. With regard to its dimensions related to digital competence, the questionnaire considers “media literacy” (DIM A), connected with the organisation and application of technologies; “communication and collaboration” (DIM B), linked to the interaction possibilities of ICT; “research and information processing” (DIM C), oriented towards the selection and distribution of digital resources; “digital citizenship” (DIM D), based on responsible and legal digital content use; and “creativity and innovation” (DIM E), geared towards the editing and creation of technological resources. Regarding the instrument’s validity, the DCQPT achieved appropriate psychometric properties. Its reliability is excellent for the questionnaire as a whole (α = 0.931), and it was between acceptable and excellent in the different dimensions (DIM A, α = 0.838; DIM B, α = 0.792; DIM C, α = 0.889; DIM D, α = 0.904; DIM E, α = 0.925). It also satisfies the psychometric validity criteria of CFA (CMIN=176.88; GFI=0.944; PGFI= 0.758; NFI=0.993; PNFI= 0.836). For this study, a good level of reliability was achieved for the study sample described (α = 0.887).

Procedure

Considering the possibilities of cultural snapshots to work on topics of a more complex reflective and philosophical level, and with the need to adapt to technological resources that respond to young people’s interests, motivations, and habitual use, it was proposed to work with cultural e-snapshots. The field of application was the course “Theory of Education”, corresponding to the first semester of the first year of the Primary Education degree. This subject consists of three main blocks of content: the concept of education, where the nomological network of this term is analysed, as well as the characteristics of teachers’ professional identities and the potential archetypes into which they can be categorised; social aspects in education, addressing aspects of the social sphere from a pedagogical perspective, including topics such as axiology, human rights, inclusion, interculturality, and pedagogy of death; and the educational institution, which examines the factors that condition the reality of different educational centres, focusing on their pedagogical-axiological model, types of leadership, and conflict management within the educational community.

On the basis of this context, interest was placed on the topic of axiology, where students would have to work on the educational perspective of values, as well as the processes of understanding and developing them. The field of values is subject to the world of ideas, building off the subjective axiological school where subjects analyse reality and form ideas to be able to understand and act on it. Within the axiological categories of a moral nature, values such as tolerance, respect, freedom, truth, and justice are part of the classwork and of learning how to teach them in future teaching jobs. The very complexity of the ideas associated with these values generates a field of knowledge within the constructivist epistemological paradigm that is continuously open to debate, reflection, and reconstruction. In the face of the difficulty posed by learning about the reality of these values through simple teacher explanations, the use of cultural snapshots favours the exemplification of this concept with people’s actions, thereby promoting a much more efficient and quality understanding.

Faced with the challenge of not only ensuring pre-service teachers’ assimilation of such values, but also being able to explain them to pre-service teachers with a psycho-evolutionary level typical of the ages that comprise primary education in Spain (6-12), it was decided to create e-snapshots as an educational resource. In this way, the students were responsible for creating narratives with characters that would experience and demonstrate aspects related to the proposed values, having to transform these narratives into more attractive digital resources for young people, such as short videos, blogs, or podcasts. The approach consisted in groups choosing a value among those proposed, without repeating any choices, and developing various narratives that had to use the three elements of e-snapshots and that illustrated the characteristics of that value. Although the focus was on content, the fact that they would learn to design and develop digital resources in a cross-disciplinary way, with a resulting impact on their digital competence, could not be ignored. Taking this into account, the students were asked to respond to the Digital Competence Questionnaire for Pre-service Teachers (DCQPT) at two different times: before creating the e-snapshots (September 2021) and after their creation and submission for evaluation in the course (January 2022). The instrument was self-administered in class, but online through the Google Forms application. The reason for this was the possibility of exporting the responses as an Excel spreadsheet, which could then be opened in the SPSS program for statistical analysis. The students were asked to identify themselves with their national ID number in order to associate the pre-test and post-test answers for each participant. Only those who freely and voluntarily wished to complete the questionnaire participated, upholding the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, along with all the ethical and legal regulations linked to this kind of research.

Data analysis.

With regard to the analyses carried out, the SPSS v.25 software was used for the following:

•Descriptive statistics were examined for both moments (pre-test and post-test). The existence of significant differences was analysed using the Wilcoxon W test for related samples, since the data did not have normal distribution (KS= p. ≤.05). For effect size, Rosenthal’s r was calculated setting values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 for small, medium, and large effect sizes (Rosenthal et al., 1994).

•For the inferential analyses, with respect to the gender variable, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied to independent samples at both times, as the normality criterion was not satisfied (KS= p. ≤.05). For the difference between the pre-test and post-test, the Wilcoxon W test was used for related samples within each gender. The sizes of the significant differences were also calculated using Rosenthal et al.’s r (1994).

3. Results

The results are presented in two sections: in the first, the students’ perceptions before and after the creation of cultural e-snapshots were analysed descriptively and inferentially; and in the second, a comparative inferential analysis was carried out considering the moment of the test for each gender.

Perceptions of digital competence levels before and after creating cultural e-snapshots

The students’ perceptions regarding their level of digital competence before creating the cultural e-snapshots in class (pre-test) and after finishing them (post-test) were worked on first. A descriptive and inferential analysis was carried out (Table 1) on the results of the questionnaire that was used, taking into account the time of data collection.

Table 1. Descriptive and inferential statistics for students’ perceptions of their digital competence before and after using cultural e-snapshots

|

Dimension |

Moment |

N |

M |

DT |

Z |

p. |

r |

|

A |

Pre-test |

113 |

6.94 |

1.35 |

–6.153 |

.000 |

0.423 |

|

Post-test |

8.06 |

1.02 |

|||||

|

B |

Pre-test |

113 |

6.16 |

0.99 |

–7.242 |

.000 |

0.536 |

|

Post-test |

7.58 |

1.23 |

|||||

|

C |

Pre-test |

113 |

6.20 |

1.18 |

–7.622 |

.000 |

0.558 |

|

Post-test |

7.78 |

1.17 |

|||||

|

D |

Pre-test |

113 |

6.74 |

1.43 |

–6.546 |

.000 |

0.461 |

|

Post-test |

8.14 |

1.26 |

|||||

|

E |

Pre-test |

113 |

5.97 |

1.24 |

–7.958 |

.000 |

0.542 |

|

Post-test |

7.44 |

1.03 |

|||||

|

TOTAL |

Pre-test |

113 |

6.40 |

0.96 |

–7.987 |

.000 |

0.593 |

|

Post-test |

7.80 |

0.94 |

The results indicate that before creating the cultural e-snapshots, all the dimensions of the instrument and the overall result of it revealed student perceptions of an acceptable digital competence level, with media literacy (DIM A) being rated the highest (M=6.94), while creativity and innovation (DIM E) was the lowest (M=5.97), yielding a 0.97-point difference between the two dimensions. After creating the e-snapshots, all the dimensions reached a notable perception level. Among them, the digital citizenship dimension (DIM D) was rated the highest (M=8.14), increasing by 1.40 points between the pre-test and the post-test. On the other hand, the dimension on creativity and innovation (DIM E) obtained the lowest results (M=7.44), despite the students’ creation of cultural e-snapshots, thereby repeating the same evaluation as before (M=97). It is worth highlighting the existence of significant differences between the results from before and after creating the e-snapshots in all the dimensions and the overall questionnaire, marking an improvement in the students’ digital competence after their creation. The effect sizes for these differences are medium-low in DIM A (media literacy) and DIM D (digital citizenship); whereas, in DIM B (communication and collaboration), DIM C (research and information processing), DIM E (creativity and innovation), and the overall questionnaire, the effect sizes are medium.

Analysis of student perceptions according to gender and moment

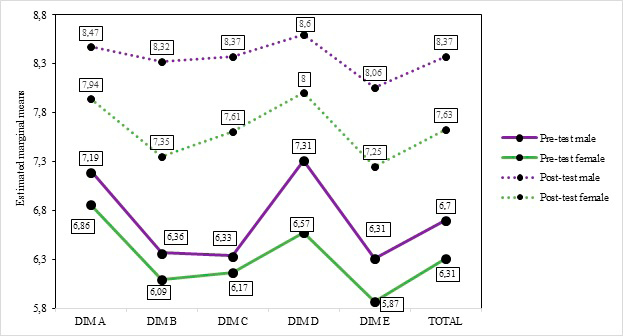

The scores of the dimensions and the total scores of the instrument, considering the gender and time variables, appear in Figure 1. Before comparing the results according to gender at each moment, it should be noted that in all dimensions and the overall instrument, regardless of the time analysed (pre-test or post-test), the male students exhibited higher perceptions of their digital competence than the female students.

Figure 1. Students’ perceptions of their digital competence before and after creating cultural e-snapshots according to gender.

Focusing on the perceptions at hand, the media literacy dimension (DIM A) went from a high acceptable evaluation for female participants (M=6.86) and a low notable one for males (M=7.19), with no significant differences between their scores (w=-.873; p=.383), to high notable ratings with significant differences (w=-2.806; p=.005) and a small effect size (r=0.251).

For the dimension on communication and collaboration (DIM B), before creating the cultural e-snapshots, an acceptable perception was obtained for both genders (males, M=6.36; females, M=6.09), yielding significant differences before the creation of the cultural e-snapshots (w=-2.060; p=.039), with a very small effect size (r=0.145). This disparity was maintained in the post-test, where both genders reached a notable rating (males, M=8.32; females, M=7.35), also maintaining significant differences (w=-3.709; p=.000), although the effect size was not as small (r=0.397).

Regarding the skills related to research and information processing (DIM C), an acceptable rating was obtained for men (M=6.33) as well as for women (M=6.17) in the pre-test, with no significant differences between the genders (w=-1.164; p=.244); whereas, in the post-test, with notable perceptions for both (males, M=8.37; females, M=7.61), the differences in the scores were significant (w=-2.851; p=.004) with a small effect size (r=0.329).

As far as digital citizenship (DIM D) is concerned, it was the highest-rated dimension by both genders and at both moments, except for the female participants’ scores before creating the cultural e-snapshots (M=6.57). As for the contrast between genders, the differences were significant both before creating the e-snapshots (w=-1.977; p=.048) with a small effect size (r=0.263) and after creating them (w=-2.124; p=.034), maintaining the small effect (r=0.257).

The creativity and innovation dimension (DIM E) presents the lowest scores at both moments and for both genders. In the pre-test, the difference in perceptions (males, M=6.31; females, M=5.87) was significant (w=-2.088; p=.037), with a very small effect size (r=0.179), which also occurred in the post-test, where with a notable evaluation for both genders (males, M=8.06; females, M=7.25) there were significant differences (w=-3.309; p=.001) with a small effect size (r=0.369).

Lastly, looking at the overall results of the test, the acceptable pre-test rating for both genders (males, M=6.70; females, M=6.31) had significant differences (w=-2.304; p=.021) with a small effect size (r=0.218); whereas, in the post-test, both male (M=8.37) and female participants (M=7.63) gave notable ratings, with significant differences (w=-3.592; p=.000) and a small effect size (r=0.387).

Table 2. Wilcoxon W test for related samples between pre-test and post-test perceptions according to gender

|

Dimension |

Male |

Female |

||||

|

W |

p. |

r |

W |

p. |

r |

|

|

DIM A |

–3.701 |

.000 |

0.502 |

–5.068 |

.000 |

0.407 |

|

DIM B |

–4.376 |

.000 |

0.726 |

–5.881 |

.000 |

0.490 |

|

DIM C |

–4.270 |

.000 |

0.697 |

–6.324 |

.000 |

0.519 |

|

DIM D |

–3.511 |

.000 |

0.506 |

–5.622 |

.000 |

0.461 |

|

DIM E |

–4.396 |

.000 |

0.615 |

–6.695 |

.000 |

0.528 |

|

TOTAL |

–4.373 |

.000 |

0.729 |

–6.690 |

.000 |

0.567 |

Level of significance p=.05

Regarding the inferential analysis, the pre-test and post-test results according to the gender variable are shown in Table 2. Significant differences were found for both male and female participants at both moments, with effect sizes varying between medium and medium-low for females, while for males it was medium to medium-high.

4. Discussion

This section is constructed based on the objectives formulated for the study. With respect to student perceptions, the results of this study show a notable evaluation of the general competence level, coinciding with Aguilar et al. (2022) and contrasting with Cañete et al. (2022), where the level found was basic. It should be noted that the creation of the e-snapshots has had a significant impact, since the general competence level before their creation was acceptable in all the dimensions and the overall instrument, rising to a notable level after their creation. This confirms that working on and creating narratives about the same topic with different technological resources influences the development of digital competence. This relationship has also been seen in other studies where the elements that compose e-snapshots were used. In this way, regarding the creation and use of videos, different studies (Cassay & Shafirova, 2021; Moreno et al., 2020) have recorded improvements in digital competence. As for blogs, studies by Álvarez (2018) and Marín (2016) indicate their influence on knowledge acquisition and the development of digital competence. For podcasts, in addition to boosting digital competence, the increase in motivation (García-Hernández et al., 2022) and self-esteem (Ortega, 2019) that they provoke should be noted.

Regarding the influence of gender and time, the findings revealed a higher level of digital competence in male participants than in females at both moments. Thus, although the creation of cultural e-snapshots improves levels of digital competence in both genders, with significant differences being found for both males and females between the pre-test and post-test, the male participants have higher perceptions of their technological skills both before and after the creation of the e-snapshots. These results coincide with those of Aguilar et al. (2022) and Cañete et al. (2022), where male participants obtained better results regarding digital competence levels with significant differences. However, these findings contradict studies such as one by Usart et al. (2021) where no differences between genders were found.

5. Conclusions

Cultural snapshots constructed around narratives in cinema, literature, and music allow more complex and abstract contents to be addressed in teaching and learning processes for better understanding. This is achieved thanks to the observation of the characters’ behaviours, which has an emotional link (Bisquerra & García, 2018), with a fundamental role being generated by these protagonists. In today’s digital society, these cultural elements can be replaced by other more current and attractive ones for students, thanks to technological advances. In this way, e-snapshots, both new ones created by teachers or students and already existing ones, are composed of different elements. In this study, blogs, podcasts, and videos have been created by students, with the focus being placed on how these creations have favoured the development of pre-service teachers’ digital competence.

The findings reinforce the idea that working with e-snapshots has a positive impact on digital competence. Moreover, these provide technology-mediated resources that allow for more abstract contents to be addressed more simply and effectively.

In this way, the concept of cultural e-snapshots can provide the scientific community with a new approach on the selection and/or production of digital resources, where the relevance of narratives and stories for the learning process is prioritised and where a higher level of attractiveness and a greater link to the interests of young people can be found in different channels (social media, podcasts, YouTube, etc.). The aim is to reinforce the perspective that the adaptation of educational processes in digital contexts involves being open to new formats that have greater significance for learners.

Limitations

With regard to the sample, the non-random selection (convenience sampling) affects the potential generalisation of the results, along with the total number of participants.

As for the resource involved, although the elements that compose cultural e-snapshots have been worked on independently (both their creation and their use in teaching and learning processes), the creation of this resource as a proposal is original and does not have precedents for direct evaluation and discussion.

Future lines of research

In addition to increasing the number of subjects in the sample, as well as carrying out probability sampling of the potential participants, it is necessary to continue delving into the educational possibilities of cultural e-snapshots by conducting more studies and experiences where these resources are used or created. In this way, their impact on aspects such as academic performance, motivation towards learning, or their inclusion within other active methodologies that have already been implemented and that have a greater presence in existing research, such as the flipped classroom or project-based learning, may be evaluated. The comparison between the influence of cultural snapshots and e-snapshots may also be relevant, as cinema, literature, and music continue to play an important role in young people’s free time. As a result, the benefits of updating formats could be seen, as well as whether the relevance lies more in the resource’s conceptualisation than in its mode of dissemination. Lastly, in order to determine the true influence of the resource, conducting studies with a control and experimental group may provide evidence of the real differences that exist in its use.

REFERENCES

, & (2009). La blogosfera educativa: nuevos espacios universitarios de innovación y formación del profesorado en el contexto europeo. Revista electrónica interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado, 12(3), 165-172. https://rabida.uhu.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/10272/6299/La_blogosfera_educativa.pdf?sequence=2

, , , & (2021). COVID-19 y competencia digital: percepción del nivel en futuros profesionales de la educación. Hachetetepé. Revista científica De Educación Y Comunicación, (24), 1102. https://doi.org/10.25267/Hachetetepe.2022.i24.1102

(2018). La utilización de los nuevos contextos digitales como una herramienta alternativa para la enseñanza de la Historia. IJNE. International Journal of New Education, (2), 95-113. https://doi.org/10.24310/IJNE1.2.2018.5191

(2011). A Social Cognitive perspective on Positive Psychology. International Journal of Social Psychology, 26(1), 7-20. https://doi.org/10.1174/021347411794078444

, & (2021). Aprendizaje-servicio en la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana seccional Bogotá, una experiencia de institucionalización en curso. RIDAS, Revista Iberoamericana de Aprendizaje Servicio, (12), 59-70. https://doi.org/10.1344/RIDAS2021.12.7

, & (2018). La educación emocional requiere formación del profesorado. Revista del consejo escolar del estado, 5 (8), 15-27. https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11162/178704/Bisquerra_Educacion_Emocional.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

, , & (2020a). Evaluation of Teacher Digital Competence Frameworks Through Expert Judgement: the Use of the Expert Competence Coefficient. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 9 (2), 275-293. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2020.7.578

, , , & (2020b). Validación del cuestionario de competencia digital para futuros maestros mediante ecuaciones estructurales. Bordón, 72 (2), 45-63. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2020.73436

, , & (2022). La formación virtual en tiempos de COVID-19. ¿Qué hemos aprendido? IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, (17), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.6361

, , , & (2022). Competencia digital de los futuros docentes en una Institución de Educación Superior en el Paraguay. Pixel-Bit. Revista De Medios Y Educación, (63), 159-195. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.91049

, , & (2017). DigComp 2.1: the Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with eight proficiency levels and examples of use. Publication Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/38842

, & (2021). “¡Ya está! Me pongo a filmar”: Aprender grabando vídeos en clase. Revista signos, 54(107), 893-918. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-09342021000300893

(2014). El mundo de los valores: una aproximación teórica al concepto de valor y sus características. Revista de ciencias de la educación, (237), 25-37.

, , , & (2022a). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of the role of ICT in attending to students with functional diversity. Educational Technology and Functional Diversity. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11212-3

, , , & (2022b). Analysis of Prospective Teachers’ Perceptions of the Flipped Classroom as a Classroom Methodology. Societies, 12 (4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12040098

(2017). ISTE standards for educators: a guide for teachers and other professionals. International Society for Technology in Education.

(2016). La formación del carácter de los maestros. Universitat de Barcelona Edicions.

, , , & (2022). Competencias clave, competencia digital y formación del profesorado: percepción de los estudiantes de pedagogía. Profesorado. Revista de Curriculum y Formación del Profesorado, 26(2), 7-27. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v26i2.21227

(2022). Radio, televisión, audio y vídeo en educación. Funciones y posibilidades, potenciadas por el COVID-19. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana De Educación a Distancia, 25(1), 09–28. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.25.1.31468

, , , & (2022). Innovación en la docencia de Fundamentos de la Geografía a partir de la elaboración de recursos de audio. En J. M. Ribera y M. M. Sáenz (Eds.), La innovación como motor para la transformación de la enseñanza universitaria (pp. 281-289). Universidad de la Rioja

, & (2020). Voces domesticadas y falsa participación: Anatomía de la interacción en el podcasting transmedia. Comunicar, XXVIII(63), 97-107. https://doi.org/10.3916/C63-2020-09

, , & (2022). Didáctica del podcast en el programa PMAR. Una experiencia de aula en la Comunidad de Madrid. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana De Educación a Distancia, 25(1), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.25.1.30618

, & (2019). Council of Europe Cultural Heritage and Education Policy: Preserving Identity and Searching for a Common Core? Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 22 (1), 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/reifop.22.1.354641

, , & (2020). El papel de la escuela en la promoción del patrimonio cultural. Un análisis a través del folklore. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 23(3), 67-82. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.384021

, , & (2020). La formación de los jóvenes para el trabajo desde la relación entre cultura y educación. Opuntia Brava, 12 (3), 9-18.

, , , & (2020). Proyección pedagógica de la competencia digital docente. El caso de una cooperativa de enseñanza. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, (14), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.3844

, , , & (2019). Patrimonio, currículum y formación del profesorado de Educación Primaria en México. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 22 (1), 83-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/reifop.22.1.358761

(2016). El blog: pensamiento de los profesores en formación en educación primaria. Opción, 32(79), 145-162. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/310/31046684009/html/

, , , & (2020). El blog en la formación de los profesionales de la educación. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 23(2), 113-126. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.414061

, , , & (2019). Competencia digital transversal en la formación del profesorado, análisis de una experiencia. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 5(1), 4-12. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2019.v5i1.4890

, , , & (2020). An Assessment of the Impact of Teachers’ Digital Competence on the Quality of Videos Developed for the Flipped Math Classroom. Mathematics, 8(2), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8020148

(2022). Inteligencia Emocional (Salovey y Malovey) y aprendizaje social en estudiantes universitarios. RES NON VERBA Revista Científica, 12(2), 16-29. https://doi.org/10.21855/resnonverba.v12i2.654

(2019). Uso del podcast como recurso didáctico para la mejora e la comprensión auditiva del inglés como segunda lengua (L2). Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos, 25(2), 9-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.20420/rlfe.2019.378

, & (2016). Experiencia universitaria con blogs en Educación para la Salud. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, (5), 150- 159. https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/IJERI/article/view/1607

(2014). La educación, crisis paradigmática y sus mediaciones. Sophia, Colección de Filosofía de la Educación, (17), 101-119. https://doi.org/10.17163.soph.n17.2014.18

, & (2022). YouTube y el aprendizaje formal de matemáticas. Percepciones de los estudiantes en tiempos de COVID-19. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2022.v8i2.14516

, & (2020). Albert Bandura: impacto en la educación de la teoría cognitiva social del aprendizaje. PADRES Y MAESTROS, (384), 72-76. https://doi.org/10.14422/pym.i384.y2020.011

, , , & (2021). Las familias ante la encrucijada de la alfabetización mediática e informacional. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 7(2), 46-58. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2021.v7i2.12404

(2020). Tutoriales de Youtube como estrategia de aprendizaje no formal en estudiantes universitarios. RIDE Revista Iberoamericana Para La Investigación Y El Desarrollo Educativo, 11(21). https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v11i21.797

, , & (1994). Parametric measures of effect size. The handbook of research synthesis, 621(2), 231-244.

(2022). Educación, cultura y valores sociales a lo largo de la dimensión temporal. Revista Educaçao e cultura contemporânea, 19(58), 222-232. http://periodicos.estacio.br/index.php/reeduc/article/viewArticle/10810

, , & (2021). Validation of a tool for self-evaluating teacher digital competence. Educación XXI, 24(1), 353-373. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.27080