Idris Khan: Time and Memory Encapsulated

Idris Khan: tiempo y memoria encapsulados

Salvador Jiménez-Donaire-Martínez

Universidad de Sevilla, España

Recibido: 30/12/2021 | Aceptado: 10/06/2022

|

Abstract |

Keywords |

|

|

British artist Idris Khan (Birmingham, 1978) has recently gained international acclaim by making artworks that evoke and dissolve ideas of time, memory and experience. Employing photography, painting, sculpture or moving image, and by prolonged processes of both accumulation and erasure, Khan experiments with temporal condensation and the notion of remembrance. This text examines a selection of his works from 2001 to the present. The impulse of making photographs long surpasses our ability –or time, or will– to reminisce in captured memories. This article analyses the implications and dynamics of this visual saturation through Khan’s recent work, placing it in relation to the ideas of authors and thinkers who address this growing problem. |

Idris Khan Photography Time Memory Visual saturation Contemporary art |

|

|

Resumen |

Palabras clave |

|

|

En la última década, el artista británico Idris Khan (Birmingham, 1978) ha obtenido reconocimiento internacional al producir imágenes que evocan y disuelven ideas sobre el tiempo, la memoria y la experiencia. A través de la fotografía y otros medios como la pintura, la escultura o el vídeo, y mediante procesos prolongados tanto de acumulación como de borrado, Khan experimenta con la condensación temporal y la noción de recuerdo. Este texto examina una selección de sus obras desde 2001 hasta la actualidad. El impulso de fotografiar supera largamente nuestra capacidad –o tiempo, o voluntad– para recrearnos en esos recuerdos capturados. El presente trabajo analiza las implicaciones y dinámicas de esta saturación icónica a través de la obra de Khan, poniéndola en relación con ideas de autores y pensadores que abordan esta creciente problemática. |

Idris Khan Fotografía Tiempo Memoria Saturación icónica Arte contemporáneo |

Cómo citar este trabajo / How to cite this paper:

Jiménez-Donaire-Martínez, Salvador. “Idris Khan: Time and Memory Encapsulated.” Atrio. Revista de Historia del Arte, no. 29 (2023): 222-242. https://doi.org/10.46661/atrio.7325.

© 2023 Salvador Jiménez-Donaire-Martínez. Este es un artículo de acceso abierto distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0. International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Introduction

Back in 1970, Italo Calvino already certified in Gli amori difficili that “the line between the reality that is photographed because it seems beautiful to us and the reality that seems beautiful because it has been photographed is very narrow”[1]. The pulsion to take photos has grown as much as to condition memory and the way people see the world, now shaped by a frozen, captured image:

When spring comes, the city’s inhabitants, by the hundreds of thousands, go out on Sundays with leather cases over their shoulders. And they photograph one another. They come back as happy as hunters with bulging game bags; they spend days waiting, with sweet anxiety, to see the developed pictures (…). It is only when they have the photos before their eyes that they seem to take tangible possession of the day they spent, only then that the mountain stream, the movement of the child with his pail, the glint of the sun on the wife’s legs take [sic] on the irrevocability of what has been and can no longer be doubted. Everything else can drown in the unreliable shadow of memory[2].

Thus, the Italian writer ironized the compulsive instinct to register every moment through photography. Now, five decades later, digitalization and the ubiquity of multi-lens cameras and screens make it even harder not to contemplate the world (exclusively) through captured images. We communicate, discover places, and take mental notes by sending, storing, and taking pictures. Once you start, suggested Calvino, there is no reason to stop. Consequently, one must either live in the most photographable way possible or be consider photographable every moment of their life. According to the author, the first option would lead to stupidity; the second, to madness.

And, indeed, there is a certain kind of insanity in today’s omnipresence of lens and webcams and front-and-rear mobile phone cameras ready to record our faces and private spaces. The proliferation of visual capturing devices testifies the dissolution between the eye-camera binomial. Spanish thinker Juan Martin Prada argues that optical head-mounted displays such as Google Glass or Go-Pro cameras transform life experience into some sort of 3D videogame[3]. With these kinds of wearable apparatuses, hands now free, cameras are fixed to the body – cameras become the body. Martín Prada laments the imposition of a new visual regimen: “Visual perception is becoming progressively automated, electronically assisted. The progressive sacrificing of vision in terms of the phenomenological/corporal relationship of man with the world, in favour of a sweetened version: ‘visualisation’. Vision that is seeing what has been framed on the screen, vision with the absence of direct sight, delegated to the technical eye of the camera. Its technical discipline, ‘visionics’, is the clearest example of vision becoming optics, a technique or a technology”[4].

Accordingly, seeing would no longer be an action or a biological experience but a simultaneous technical record to be stored in an external hard disk, instead of a proper, conscious observation. The author describes a dizziness inherent to this visual schedule, in which there seems to manifest a certain “hunger of time”[5]. The greater accessibility and facility to capture images has forced a process of acceleration of seeing. Digital photography has entirely eradicated the waiting times between the shooting and the manifestation of the registered image, an ineludible intermediate phase in analog or film photography (as earlier described by Calvino). Now, Martin Prada suggests, everything is immediate appearance: instant epiphany. In this regard, the term snapshot became popular in the second half of the 19th Century when describing an instantaneous, prompt photography usually taken by amateurs and shot with cheap, handheld cameras. Significantly homophonous, Snapchat was born in 2011 as a multimedia instant messaging app. It allows sharing photos or short videos from 1 to 10 seconds, as determined by the sender, then the image is no longer available to see. Talk about immediacy of gaze.

Through the work of Idris Khan, this text addresses the growing problematic of image overabundance and its imbrications regarding time and memory. Born in Birmingham in 1978, the photographer’s prominence in the art world has increased exponentially during the past decade. Both figurative and abstract, Khan’s images are formally destructive and emotionally constructive, personal and collective, memory evoking yet made-up, time condensing and time stretching.

Layers of time

Photography beneath photography. The Every… series (2004)

“If all of time were to be reduced to a single moment, the world might look like one of Idris Khan’s works”[6]. In his practice, the artist’s main interest has always revolved around photography, the medium which helped him gain critical recognition in the early 2010’s. Since then, Khan has been commissioned to realize permanent public monuments via sculpture (the most significant to date being a massive memorial at Wahat Al Karama, Abu Dabi, installed in 2016) and invited to collaborate across other art forms and contexts, such as choreographic and video pieces. In recent years, and as an expansion of his interest in the pictorial aspects of photography, Khan has started making bold, monochrome paintings on canvas and glass. An early photograph from 2001, White Court, proves the intersectionality that the artist sees in the formal qualities of both mediums. The image shows the back end of a squash court and the marks made by the balls and racquets on the wall, which recalls Cy Twombly’s intuitive mark-making paintings. In an interview led by Thomas Marks, Khan describes this photograph and recognizes the impact of American painters in his oeuvre: “It’s almost an abstract painting that people have made accidentally, and somehow the camera gives it order (…) Obviously Abstract Expressionism has always been a huge part of my work and influence on me (…) [There’s an] element of intrigue regarding the relationship that photography has with painting – the idea that a photograph might look more like a drawing or a charcoal drawing, or have more of a painterly quality”[7].

This early work is also noteworthy because it introduces another fundamental aspect of Khan’s photography: a temporal dimension. White Court was taken employing a considerably long exposure, 20 minutes, so there is real time registered on the picture. On this technical and conceptual photographic strategy, the artist declares: “That’s what so beautiful for me – to capture this moment, of traces of time passing”[8].

It is the nature of the photographic act, indeed, what originally activated his research, which is informed by history of art, music, and key philosophical and theological texts. Indistinctively of the media, Khan investigates memory, time, and the layering of experience. A formally trained artist, he moved to London to enroll at the Royal College of Art for his MA. By then, he was determined to become a photographer, but during his first year he was exposed to new philosophers and theorists like Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, Friedrich Nietzsche… and he stopped making photographs. Overloaded with this new information and frustrated by not knowing how to incorporate them into his work, Khan decided to use all these references in a single image (Figure 1):

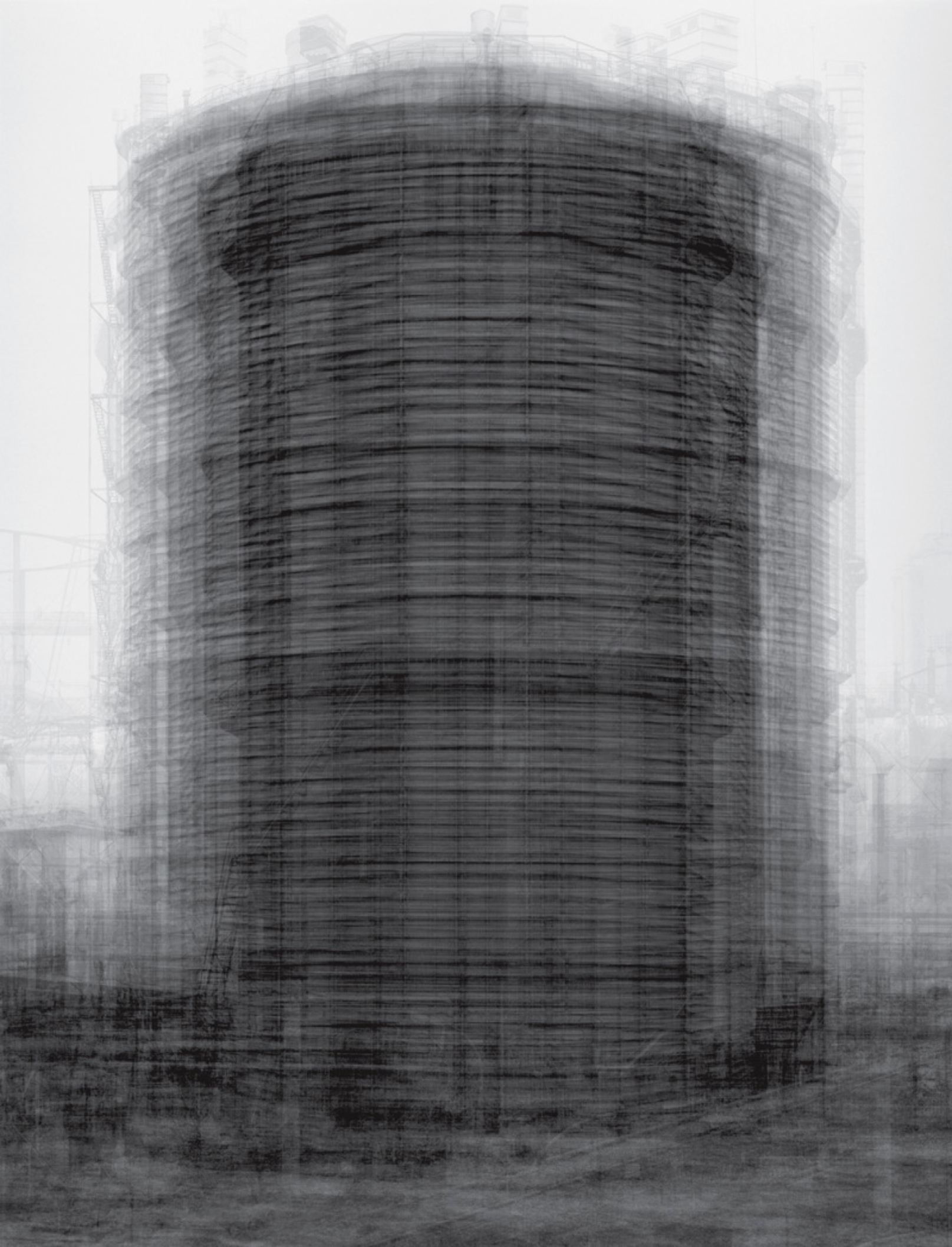

One of the first works I made during that period was a series on the Bechers, Bernd and Hilla Becher, who are very famous German photographers who captured the industrial buildings of Europe obsessively. I remember it so clearly. I was sitting in my flat in Blackheath at the time, which is where I first moved when I came to London, and I held up the book and this quality of light came through the window, and two images were merged together… I think it was two gas towers together. There was an incredible ethereal quality of the light transmitting through these layers, these pages, and it no longer looked like a photograph. It looked like a drawing[9].

Figure 1. Idris Khan, Homage to Bern Becher, 2007. © The Phillips Collection.

This is how the Every… series was born, the work that rose him to prominence. In this exercise of appropriation and composite photography, Khan gathered well-known photographs and overlapped them, using digital tools to reduce or intensify the opacity of the layers. The resulting image is mysterious, evasive, slippery. About this process, Khan says: “you can create more than just a document –a feeling of stretched time. I try to capture the essence of the building– something that’s been permanently imprinted in someone’s mind, like a memory”[10].

The experiment quickly evolved from using photography as a starting point to painting, as in the case of Every... William Turner postcard from Tate Britain (2004). The works have a phantasmagorical, blurred quality. New shapes appear whilst others become imperceptible due to redundancy; cumulation both reveals and eradicates.

Aside from this pictorial appearance, unusual in the photographic medium, what fascinates the most in the proposal is how a single image holds vast quantities of time. Significatively, the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher is shaped by an obsessive, time-demanding control of the photographic shot. The couple spent their entire career and lives coming back to the same theme. The “homage” paid by Idris Khan to the couple’s work offers both a melancholic interpretation and a poetic reminder of time passage. The artist himself emphasizes the temporal aspect of the original oeuvre: “I was interested in the time it took them to wait for the perfect light to cast no shadows and to flatten the perspective to a point where the work is not about beauty, it became more about interconnecting lines”[11].

Similarly, the work Every... Nicholas Nixon’s Brown Sisters (Figure 2) exultates the slow production process of the original photographs. As in the work by the Bechers, Nicholas Nixon has dedicated a substantial part of his career to capturing portraits of his wife and three sisters. For over 40 years, the relatives have posed in front of his camera in an exercise of reminiscing, vulnerability, celebration, exposure and, ultimately, aging. By superposing Nixon’s photographs (from over 20 years by the time the work was made), Khan condenses all those years and lives into a single moment. The sisters’ faces are no longer recognizable: their figures have become stain, blur, air. “In Khan’s composite, the sitters appear to turn to stone. They have become monumental, sepulchral, and eternally petrified”[12].

Figure 2. Idris Khan, Every... Nicholas Nixon’s Brown Sisters, 2004. © The Phillips Collection.

In these multilayered photographs, time is a meaningful unit in itself. In his works, time is densified instead of stopped, as Khan himself explains: “It’s hard to avoid the aspect of time when producing what one sees as a photograph. The viewer observes one of my images as something that is not a frozen moment but an image made up of many moments and that is created over ‘time’ rather than taken”[13].

This methodology of carefully scanning, processing, and overlapping other authors’ works, both photographs and paintings, was also employed by the artist to make works composed not by images but by words. Such is the case of Every… Page of Susan Sontag’s Book ‘On Photography’ (2004) or Every... Page of Vilem Flusser’s Book ‘Towards a Philosophy of Photography’ (2004), both fundamental texts for every apprentice of the medium and authors who Khan discovered at the Royal School of Art.

A particularly difficult work to create in the series was Every… Page of the Qu’ran, also from the year 2004. When photographing the almost 2000 pages long book, each delicate sheet had to be carefully handled. Khan’s dual heritage (his father is Pakistani and his mother was Welsh) has been traced when analyzing predominant elements to his art practice, such as repetition. Brought up a Muslim, he attended local mosques and used to recite prayers in Arabic. Although he abandoned religion when 14, until then he was taught at home to read the Qur’an, “which requires a ritualistic approach to reading and involves constant repetition”[14]. Khan himself links those memories to his activity as an artist: “I had always felt that the process of reading the Qur’an led directly to my repetitive mode of making art – you read the Qur’an a page a week, meaning you’re constantly returning to the same page. So in 2004, I made this image in my flat, using my father’s book. I scanned every single page using a computer – I think it was 1,953 pages – and then I condensed and digitally layered them, observing the correct practices of handling the book throughout. Altogether, it took two months”[15].

Repetition is indeed central to the production of these photographic works. The notion of recurrence, intimately close to temporality, blurs and distorts as well as it emphasizes and defines. Thus, reiteration nullifies meaning whilst still creating new sense. According to curator and writer Nick Hackworth, by strapping words of their force and symbolic significance, Khan returns them to the status of marks; misshaped, temporal marks, as pointed out by the artist himself: “Repetition is something my work addresses. I’m not a writer, but I like the way words accumulate. If you place words on top of one another they eradicate the words underneath and it questions whether the word is destroyed, or by repeating it, gives it a more powerful meaning. It no longer becomes a word, it becomes a trace of time”[16].

Overlapping images and words has become the artist’s preferred creative strategy, a process that arises questions linked to time, memory, creativity, spirituality and authorship. Temporality, Khan explains, is prolonged within the iterative nature of these multiplied images: “I’m using every single word in the book and creating this long-lasting image, almost looking like the book’s unfolding in front of your eyes in an instant”[17]. As Oliver Basciano argues, the act of repeating carries a spiritual weight, as it embodies a ceremonial gesture: “Repetition does something. It performs something. It changes something. In almost every one of the world’s major faiths, repetition is utilized in the act of worship. One Ayah in the Qu’ran for example –in Surah 55– is repeated 31 times. A priest might request the repeated private citation of the Hail Mary as penance in the Catholic sacrament of confession. The repetition of mantra is a central facet of meditation in various schools of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism”[18].

This section has underlined the conceptual, methodological, and symbolic imbrications of Khan’s repetitive, time-robbing process of overlapping images and words. His Every… series and superposed photographs and paintings could be read as what Martín Prada refers to as counterimages: visual configurations that emits a slower light, a denser light, demanding a prolonged optic digestion[19]. Analogously, Spanish art critic and professor Miguel Ángel Hernández defends an artistic manifestation that incites resisting time through the very introduction of other forms of time: “Tiempo desnaturalizado, profanado, tiempo de vida, subjetivo, tiempo de la duración, tiempo del pasado, tiempo de memoria”[20]. In the smudged forms of Khan’s multi-layered, palimpsest-like photographs, time seems to find a way out.

Loss, memory and images. My mother (2019)

In a photograph, we look at something that has been and no longer is. Roland Barthes referred to this as time ecrasé –crushed time–, writing on his Camera Lucida: “The Photograph then becomes a bizarre medium (…): false on the level of perception, true on the level of time: a temporal hallucination (…) (on the one hand ‘it is not there,’ on the other ‘but it has indeed been’)”[21]. Barthes ruminates on his text about his late mother’s absence, yet present in pictures. “Death is the eidos of Photography”[22], the author states; in other words: past is the form of photography. Similarly, Susan Sontag sustains that all photographic images are memento mori, a reminder of death: “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt”[23]. Indeed, it is often said that cameras halt time, therefore suspending life and its transience.

Peter Hujar’s 1973 portrait of Candy Darling lying on her deathbed comes to mind. Warhol’s muse and transgender icon rests on the hospital bed, surrounded by a multitude of flower bouquets. Eyes all black in make-up, she stares at the camera. In a surrendered yet defying gesture, she gazes back at us as if both tired and implacable. Candy is captured neither alive nor dead – her beauty kept forever in the photographic limb. Hujar’s work, celebrated by the lingering atmosphere of his squared, black-and-white portraits, exemplifies the potential of photography to move between those dualistic realms: life and death, present and past, presence and absence.

On his sixth novel, Immortality, Milan Kundera writes: “memory does not make films, it makes photographs”[24]. Undoubtedly, remembrance and photography are united since the latter’s origin. If memory, as suggested by Kundera, works by freezing events into static images, it is only logical that, since its very beginning, photography was employed as a means to make a visual record of what we are afraid of forgetting, of losing – including the already departed loved ones. In 1987, minutes after Peter Hujar died during the AIDS crisis, his ex-partner and close friend, David Wojnarowicz, took three pictures of his corpse: hand, face, and feet. The artist’s body lies inert, flesh reduced to bones, his face twisted and unrecognizable. The images are excruciating to witness: the details of Hujar’s unseeing eyes, darkening nails and swollen toes are piercing. “His death is now as if it’s printed on celluloid on the backs of my eyes”[25], writes Wojnarowicz on his autobiography. Surely, pictures fixate memories. Such a private scene is documented by the photographer and activist with haunting honesty and bluntness, and yet there is room for tenderness in the dark triptych of pictures. There is an elegiac weight in the very act of photographing the dead. But what is it that photography promises to restore, to bring back? South-Korean born philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues that the medium not only offers a visual testimony of the dead but also allows experiencing them as if alive once again: “La fotografía no se limita a recordar a los muertos. Más bien, hace posible una experiencia de su presencia devolviéndoles a la vida”[26]. Analogously, Barthes considered photography to be a means of resurrection[27]. Taking up this idea, Han claims that a photographic image is the umbilical cord that connects the beloved body to the one who is looking beyond death, redeeming it from decomposition[28]. Thus, the experience of human life brevity is reinforced by photography.

Many artists have addressed this issue through their lens and cameras. Nicholas Nixon focused precisely on that in his previously mentioned The Brown Sisters series. Seichii Suruya’s portraits of her wife Christine Gössler deal with the same notions of love, passing and holding on to memories. Throughout their marriage, Suruya photographed his mentally ill wife until she committed suicide in 1987. Significantly, the last image of Gössler is a photograph of a photograph of her face being developed. The developer liquid is being poured onto the image of Suruya’s dead wife, making the picture itself appear, the face of Christine coming (back) to life.

One of Idris Khan’s recent works, titled My Mother (Figure 3), revolves around all these ideas of time, memory, and loss. Khan’s approach to the matter is, however, less explicit and more conceptual. The decease of Khan’s mother had a vast impact on the artist’s career. The artist has openly talked about it on several occasions: “My most personal experience of losing someone close to me was my mother in 2010. She was fifty-nine and I was thirty, recently married and about to start a family. Nine months later grief struck again when my wife had a stillbirth very late into her pregnancy. I responded to the anger of all of this in the only way I could, by making art”[29].

Figure 3. Idris Khan, My Mother, 2019. © Sean Kelly Gallery.

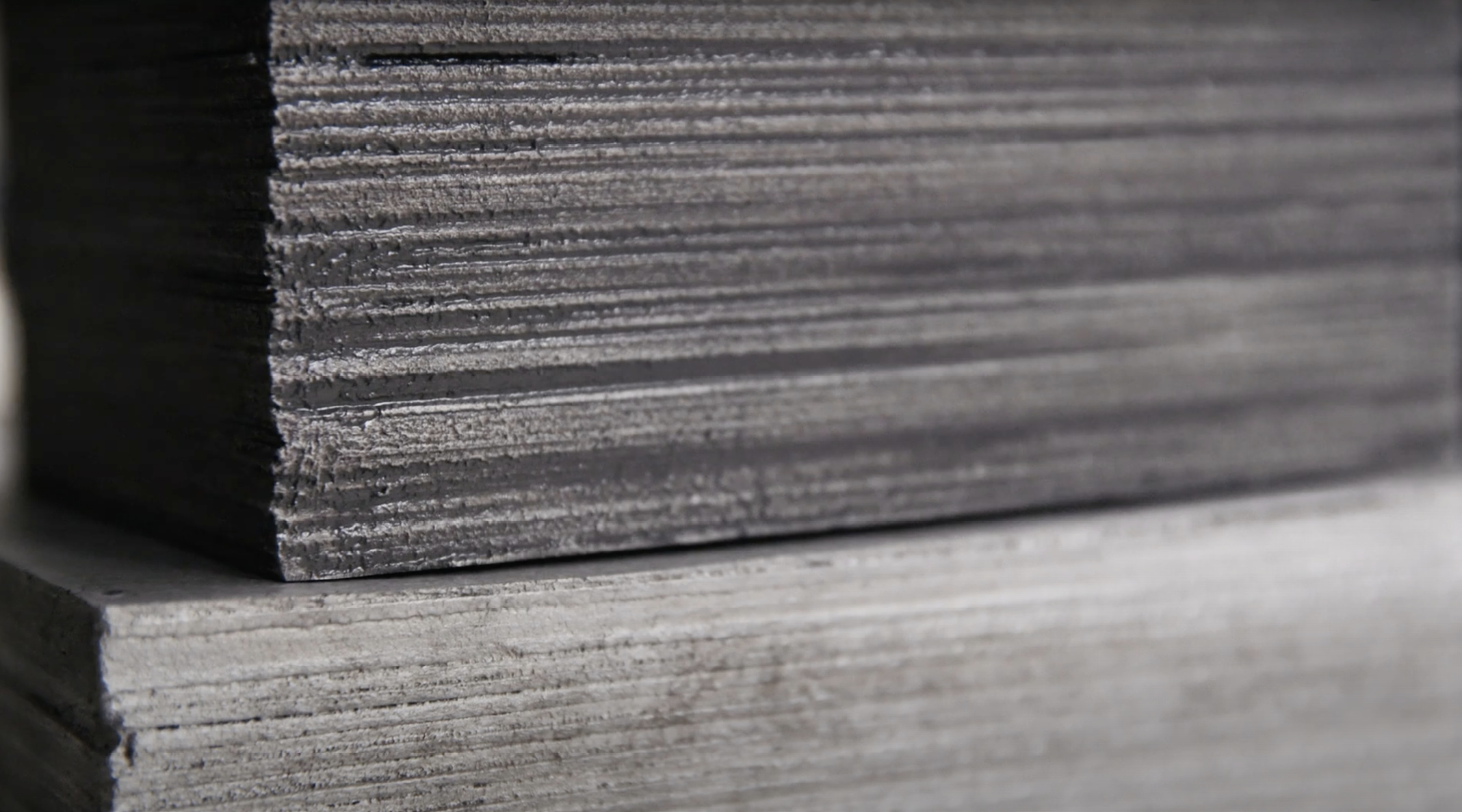

Khan’s dealing with mourning and sorrow is translated into his art elusively, discreetly. Despite its revealing title, the piece My Mother is no exemption. Idris started the process of making the work by gathering every photograph he could find of his late mother taken during her lifetime. There were about 360. He then stacked the photographs and casted the group in blue pigmented Jesmonite (Figure 4). What Khan shows is not the actual images but their volume and shape: we can see the shape of each individual photograph atop another. Khan explains: “It almost feels like the rings of a tree. I’m not showing the pictures themselves, you’re just seeing the edges of the paper. It is about using the physicality of a photograph to show time”[30]. The 21 x 10 inches sculpture recalls the form of a sepulcher, a sort of “abstract monument that collapses memory and time into a singular column”[31]. The artist believes that “through looking at these edges of the photograph, you are sort of almost looking at the nature of image making but also (…) a volume of time”[32].

Figure 4. Idris Khan, My Mother (detail of the production), 2019. © Sean Kelly Gallery.

Apparently minimalist and geometric, the tiny statue might come across as something impersonal and self-referential. However, the original material generates a deeply personal narrative, and the piece displays an intimate, emotional dimension. Ultimately, the work raises the question of image making and storing, as the number of photographs composing the piece is surprisingly low (barely 360 in a lifetime) in comparison to current standards.

The next section will address Khan’s immediate work after My Mother, titled 65ooo Photographs (also from 2019) – a piece that interrogates the pulsion to photograph others and get photographed in our digitalized world.

Into the abyss: archiving memories through digital photography

“Look how gloomy they are! nowadays the images are livelier than the people”, noticed Barthes[33]. For the French semiologist, one of the signs of our world is living according to an image-repertoire. “Everything is transformed into images: only images exist and are produced and are consumed”[34]. Mallarmé thought that everything existed in order to end in a book; Sontag responded: “Today everything exists to end in a photography”[35]. As Paul Válery certified, photography has tamed and conditioned sight: “La fotografía enseñó a los ojos a esperar aquello que debían ver”[36]. None of the mentioned authors lived enough to witness the digital thunderstorm, but they all sensed that we were ushering into a visual regime in terms of communication, thinking and even conceiving existence. “No pocas veces la lente que permite enfocar ‘da existencia’”, testifies Remedios Zafra, “Es la diferencia entre ser y difuminarse”[37]. All sorts of information, even trivial communication, adopts a visual configuration. Indeed, and as it’s been pointed out in the introduction, our lives are intertwined with all sorts of multi-lens devices and screens – apparatuses that capture, send, receive and store images, which in turn configure and transform our gaze. Our memory, which used to be selective, too. “Keep everything, share anything”, says an advertising by Google Drive. On another ad campaign by Dropbox, a scanned analogic photograph is accompanied by the words revive your family history. “For all things worth saving”, the advertisement says. “Automatic. Everywhere. iCloud”, proclaims another digital storage service. It’s not surprising that thinkers such as Martín Prada describe us as “images junkies”: “Casi todos los momentos de nuestras vidas se ven acompañados de actos de registro visual, ya casi obligados y permanentes. Es la lógica de ‘en todo momento, una fotografía’”[38]. In consequence, vision becomes a technological archiving activity: the acts of registration are compulsory, leaving experience itself on a secondary plane.

Such dynamics in the digital age motivated Idris Khan to make 65000 Photographs (Figure 5), a work that examines this imperative of image making and saving. My mother was produced in 2019. In contrast to the 300-ish photographs existing from Khan’s mother lifespan, the artist had taken –only in a five-year period– over 65000 pictures with his phone. Alluding to that vast personal archive of images, the London-based creator made a massive tower that represents the collective fervor to document our everyday life.

Figure 5. Idris Khan, 65000 photographs, 2019. © Victoria Miro Gallery.

Casted in aluminium, the work was commissioned by St George City Ltd with London Borough of Southwark as part of the One Blackfriars Public Art Programme. The tower stands 8.2 metres tall and was made following a similar procedure as in My Mother: stacking 65000 sheets of standardized photographic paper (5x7, 10x7, 12x16 inches and so on) that create a reverse-pyramid shape. Strikingly, with a height of only 53,3 cm, the sculpture My mother stood 16 times smaller. The contrast between the visual detritus of five years of a life (with digital media) and a whole lifetime (without it) is arresting when presented in this bold way. The work 65000 photographs underlines how unable we have become to separate our existence from virtual archiving and photographing: we actually identify past experiences with the latter. “It’s quite a moving thing to think that this was five years of my life,” says Khan himself, “That time has gone, but this, in some ways, is what’s left of it”[39].

Thus, the piece addresses time passing, memory keeping and the digitalization’s photographic boom. The shape of the sculpture is rather odd, inversed as it is, and in spite of referring to Khan’s personal archive, there is nothing private actually revealed in the work: as in My Mother, images themselves are not properly shown, only their physicality (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Idris Khan, 65000 photographs (detail), 2019. © Sean Kelly Gallery.

There is a certain level of abstraction and anonymousity to it – those 65000 pictures could be anyone’s, as we all participate in the same dynamics of obsessive image capturing and storing. Keep it all, the ads said. “There is this idea that cameras have replaced our eyes; we want to photograph everything before we even see it. We are all guilty of it”, Khan recognises. “I’m not there to say how many pictures you should take, but in some ways, I think it’s about the ownership we have over certain things. That comes first before the experience”[40]. In both works, My Mother and 65000 photographs, conceptually linked yet formally antagonic (in height and materials), Khan’s attempts to give body to photographs. The fact that he describes both sculptures of materialized images in terms of volumes of time is particularly significant. The image becomes an object, not a series of digital units of information. And, as an object, it is exposed to deterioration. We mentioned earlier Barthes’ ideas on photography as a means related to death. As a delicate thing, Byung-Chul Han argues, the materiality of analogic photography, or a printed photography, embodies the transience of time – its fragile materiality is related to ageing, to decadence[41]. On his essay En el enjambre, the South-Korean thinker ruminates on digital images’ lack of temporality, as their virtuality is related to a never-ending present:

[Existe en] la fotografía analógica una forma de vida para la que es constitutiva la negatividad del tiempo. En cambio, la imagen digital, el medio digital, se halla en conexión con otra forma de vida, en la que están extinguidos tanto el devenir como el envejecer, tanto el nacimiento como la muerte. Esa forma de vida se caracteriza por un permanente presente y actualidad. La imagen digital no florece o resplandece, porque el florecer lleva inscrito el marchitarse, y el resplandecer lleva inherente la negatividad del ensombrecer[42].

By casting the spatial volume of these thousands of images, the artist accentuates the disembodied, virtualized, dematerialized relationship we now have with photography. “Today, we hold more photographs in the palms of our hand than ever before, yet we physically touch next to none”[43]. In both My mother and 65000 photographies, Khan overlaps layers of printed images atop each other to evidence, to turn visible the relation between contemporary life and the cumulation of photographic record.

Culminating, expanding, unfolding. Final notes

This text has reviewed some of Idris Khan’s works in relation to time and photography as well as memory and the storing of digital imagery.

In the Every… series previously mentioned, the artist digitally overlapped scanned or appropriated images to create a condensed, quivering, blurred new one. The result is a visual configuration that is more reminiscent of painting or drawing than of the conventional quality of photography. Although photographers are often said to freeze time, here it is argued that Khan’s work does the opposite. His photographs are carefully constructed rather than “taken”. The process of scanning and then digitally laying every page of the Qu’ran, as described earlier, is a long, time-demanding and repetitive one. The very fact that this working method involves time results in a series of images that, in turn, unfold time themselves. Khan’s work Rising Series... After Eadweard Muybridge ‘Human and Animal Locomotion’, from 2005, is the perfect example. Muybridge is notorious for employing fast-shutter speeds to reveal the whole time arc of an action in stilled, individual images. Pursuing a creative strategy that constitutes his trademark as an artist, Khan combines and layers every one of them in a single image – from statism to movement, from a frozen temporality to spread time. As suggested earlier, Khan’s selective appropriation of celebrated photographic images such as the ones composing The Brown Sisters series, by Nicholas Nixon, or the work by Bernd and Hilla Becher, is significant: it emphasises the temporal dimension of his digital composites, since both original works are decades-long projects involving meticulous care and dedication. Throughout the 2000’s and the early 2010’s, Khan reiterated this approach in his practice employing several image sources, from books and photographs to music sheets. On a negative note, and as The Guardian habitual collaborator Geoff Dyer points out, “The danger is that this composite thing could just become his shtick. He could do every page of every book, every this of every that. Every… Photograph Taken Whilst Travelling Around Europe in the Summer of 2002 seems a rather pointless novelty”[44]. Dyer concludes that Khan seems to hit the target better when he applies his methods to existing works of art, as it was his original intention.

Certainly, there are precedents for and equivalents to these cumulating, overlying strategies of visual condensation. The works of Corinne Vionnet, for instance, come to mind. In Photo Opportunities, the Swiss artist generates intricate images composed by thousands of tourists’ snapshots taken in world-famous monuments and cities. The Golden Gate Bridge, The Big Ben or the Eiffel Tower become layered, ethereal structures quite similar to Khan’s. Vionnet’s proposal can be read as an attempt to underline the proliferation of information in the technical age. Although shot by very different people under diverse circumstances, all the photographs of those emblematic places are taken from almost the very same angle and point of view. There is this huge amount of images being taken and stored and shared and most of them look identical, which leads us to believe that we are, as Calvino, Martín Prada and other authors earlier mentioned declared, seeing exclusively through our cameras. As pointed out throughout this text, vision is becoming more a technological task of archiving than an actual perceptive experience. In this sense, Penelope Umbrico’s work is another example of the urgent need to interrogate the explosion of new images in an era that is increasingly shaped by the excess of photographs.

This visual saturation is precisely what Khan’s sculptural works My mother and 65000 photographs address. The artist admitted his own surprise when comparing the few hundred of photographs taken in the lifetime of his late mother to the many thousands of pics saved in the course of five years of his life. Often described as “experiments in compressed memories”[45]. Khan’s sculptures take indeed the form of memorials or monuments for recollection. Although evasive and conceptual, his totemic columns made out of stacked, printed photographs are thought-provoking and highlight the obsessive image making practice that has occurred since the advent of digital technologies.

Ultimately, this text has proved how the inextricable nexus between photography, temporality, mortality and remembrance is reinforced in the work of the british artist, which proves photography’s ability as a medium to expand and question ideas of time, memory and experience.

References

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill & Wang, 1982.

Basciano, Oliver. “Image, then Image.” In Idris Khan: A World Within, edited by Deborah Robinson, 13-18. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2017.

Benedictus, Leo. “My Best Shot: Idris Khan.” The Guardian, August 2, 2007. Consulted on April 1, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2007/aug/02/arts.

Benjamin, Walter. Breve historia de la fotografía. Madrid: Casimiro, 2019.

Calvino, Italo. Difficult loves and Other Stories. London: Penguin Vintage Classics, 2010.

Durden, Mark. Photography Today. London: Phaidon, 2014.

Dyer, Geoff. “Between the lines.” The Guardian, September 2, 2006. Consulted on March 11, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2006/sep/02/art.

Elkann, Alain. “Idris Khan.” Alain Elkann Interviews, May 9, 2021. Consulted on April 9, 2022. https://www.alainelkanninterviews.com/idris-khan/.

Guggenheim Museum. “Idris Khan: Conversations with Contemporary Artists (Complete Version).” Youtube, 1:02:28, December 1, 2021. May 10, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I95I7Ymk7PA.

Hackworth, Nick. “Fragments of Savagery.” In Idris Khan: Words Beneath Words, n. p. Venice: Victoria Miro Gallery. Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized and presented in Venice, 26 October - 14 December 2019.

Han, Byung-Chul. En el enjambre. Barcelona: Herder, 2013.

–––. No-Cosas. Quiebras del Mundo de Hoy. Barcelona: Taurus, 2021.

Hernández, Miguel Ángel. El Arte a Contratiempo. Historia, Obsolescencia, Estéticas Migratorias. Madrid: Akal, 2020.

“Idris Khan (b. 1978). Struggling to Hear... After Ludwig van Beethoven Sonatas”. Christie’s, (n. d.). Consulted on 23 March 2022. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5163415.

Khan, Idris. “The Death of Painting.” In Idris Khan, 8-12. Manchester: The Whitworth, The University of Manchester, 2017.

Kelly, S. [Sean Kelly Gallery]. “Idris Khan Blue Rhythms.” Youtube, April 24, 2019. Consulted on March 12, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rbLxVrudObM.

–––. “Idris Khan in #InDetail.” SKNY, July 1, 2020. Consulted on March 10, 2022. https://www.skny.com/news-events/idris-khan-in-indetail2.

Kundera, Milan. Immortality. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991.

Marks, Thomas. “Layers of Time: A Conversation with Idris Khan.” In Idris Khan: A World Within, edited by Deborah Robinson, 124-131. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2017.

Martin Prada, Juan. The digital nature of the image. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura, 2010. Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized and presented in Cáceres, March 26 - April 10, 2010.

–––. El tiempo y las imágenes en el tiempo de Internet. Madrid: Akal, 2018.

Parsons, Elly. “Idris Khan’s first UK public sculpture addresses our photo-obsessed culture.” Wallpaper, November 4, 2019. Consulted on March 30, 2022. https://www.wallpaper.com/art/idris-khan-65000-photographs-sculpture-london.

Robinson, Deborah, and Stephen Snoddy. “Foreword.” In Idris Khan: A World Within, edited by Deborah Robinson, 5-8. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2017.

Sherwin, Skye. “Artist of the week 80: Idris Khan.” The Guardian, March 25, 2010. Consulted on 22 March, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/mar/25/artist-idris-khan.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Anchor Books, 1990.

“Pretty as a Thousand Postcards.” The New York Times, March 1, 2012. Consulted on March 18, 2022. http://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2012/03/01/magazine/idris-khan-london.html.

Warner, Marigold. “Idris Khan’s 65000 Photographs.” In 1854. British Journal of Photography, November 18, 2019. Consulted on March 18, 2022. https://www.1854.photography/2019/11/idris-khan-65000-photographs/.

Wojnarowicz, David. Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration. New York: Vintage Books, 1991.

Zafra, Remedios. Ojos y Capital. Madrid: Consonni, 2015.

[1] Italo Calvino, Difficult loves and Other Stories (London: Penguin Vintage Classics, 2010), 43.

[2] Calvino, 40.

[3] Juan Martin Prada, El tiempo y las imágenes en el tiempo de Internet (Madrid: Akal, 2018), 8.

[4] Juan Martin Prada, “The digital nature of the image,” in Catálogo Premios de Arte Digital. Lúmen_ex, coord. Pilar Mogollón Cano-Cortés (Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura, 2010). Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized and presented in Cáceres, March 26 - April 10, 2010, 42.

[5] Martin Prada, El tiempo y las imágenes en el tiempo de Internet, 32.

[6] Robinson, Deborah, and Stephen Snoddy, “Foreword,” in Idris Khan: A World Within, ed. Deborah Robinson (Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2017), 5-8.

[7] Thomas Marks, “Layers of Time: A Conversation with Idris Khan,” in Robinson, 126.

[8] Marks, 126.

[9] Marks, 126.

[10] “Pretty as a Thousand Postcards,” The New York Times, March 1, 2012, consulted on March 12, 2022, http://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2012/03/01/magazine/idris-khan-london.html.

[11] Guggenheim Museum, “Idris Khan: Conversations with Contemporary Artists (Complete Version),” Youtube, 1:02:28, December 1, 2021, May 10, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I95I7Ymk7PA.

[12] Mark Durden, Photography Today (London: Phaidon, 2014), 48.

[13] “Idris Khan (b. 1978). Struggling to Hear... After Ludwig van Beethoven Sonatas,” n.d., consulted on 23 March, 2022, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5163415.

[14] Deborah Robinson and Stephen Snoddy, “Foreword,” in Robinson, Idris Khan, 7.

[15] Leo Benedictus, “My Best Shot: Idris Khan,” The Guardian, August 2, 2007, consulted on April 1, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2007/aug/02/arts.

[16] Idris Khan, “The Death of Painting,” in Idris Khan (Manchester: The Whitworth, The University of Manchester, 2010), 8-12.

[17] Alain Elkann, “Idris Khan,” Alain Elkann Interviews, May 9, 2021, consulted on April 9, 2022, https://www.alainelkanninterviews.com/idris-khan/.

[18] Oliver Basciano, “Image, then Image,” in Robinson, Idris Khan, 13.

[19] Martin Prada, El tiempo y las imágenes en el tiempo de Internet, 25.

[20] Miguel Ángel Hernández, El Arte a Contratiempo. Historia, Obsolescencia, Estéticas Migratorias (Madrid: Akal, 2020), 19.

[21] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill & Wang, 1982), 115.

[22] Barthes, 15.

[23] Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Anchor Books, 1990), 15.

[24] Milan Kundera, Inmortality (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991), 234.

[25] David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 102.

[26] Byung- Chul Han, No-Cosas, Quiebras del mundo de hoy (Barcelona: Taurus, 2021), 45.

[27] Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, 82.

[28] Han, No-Cosas, Quiebras del mundo de hoy, 46.

[29] Idris Khan, “The Death of Painting,” n. p.

[30] Marigold Warner, “Idris Khan’s 65000 Photographs,” in 1854. British Journal of Photography, November 18, 2019, consulted on April 17, 2022, https://www.1854.photography/2019/11/idris-khan-65000-photographs/.

[31] Sean Kelly, “Idris Khan in #InDetail,” SKNY, July 1, 2021, consulted on April 22, 2022, https://www.skny.com/news-events/idris-khan-in-indetail2.

[32] Sean Kelly, “Idris Khan Blue Rhythms,” Youtube, 3:45, April 24, 2019, consulted on April 24, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rbLxVrudObM.

[33] Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, 118.

[34] Barthes, 118.

[35] Sontag, On Photography, 24.

[36] Walter Benjamin, Breve historia de la fotografía (Madrid: Casimiro, 2019), 48.

[37] Remedios Zafra, Ojos y Capital (Madrid: Consonni, 2015), 11.

[38] Martin Prada, El tiempo y las imágenes en el tiempo de Internet, 103.

[39] Warner, “Idris Khan’s 65000 Photographs.”

[40] Warner.

[41] Han, No-Cosas. Quiebras del Mundo de Hoy, 45.

[42] Byung-Chul Han, En el enjambre (Barcelona: Herder, 2013), 37.

[43] Elly Parsons, “Idris Khan’s first UK public sculpture addresses our photo-obsessed culture,” Wallpaper, November 4, 2019, consulted on March 30, 2022, https://www.wallpaper.com/art/idris-khan-65000-photographs-sculpture-london.

[44] Geoff Dyer, “Between the lines,” The Guardian, September 2, 2006, March 29, 2022, consulted on March 11, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2006/sep/02/art.

[45] Skye Sherwin, “Artist of the week 80: Idris Khan,” The Guardian, March 25, 2010, consulted 22 March, 2022, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/mar/25/artist-idris-khan.